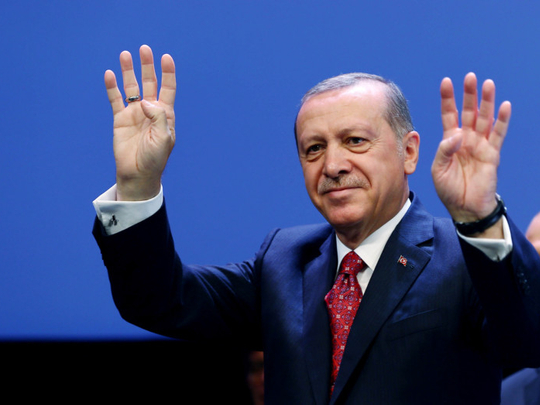

The visit of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to Russia and his meetings with President Vladimir Putin have opened the door to a flood of commentary and analysis on the war in Syria and its course. Though Turkish-Russian relations are important in itself, not only economically but politically as well, Syria was the focus of the Turkish-Russian summit. Few days after the Erdogan-Putin meeting, Russia deployed batteries of its advanced missile system (S400) in Crimea, raising stakes of military tension with Ukraine. We didn’t hear the same old rhetoric from Erdogan this time against Russia and for the Muslim Tatar majority in that region. On the contrary, it coincided with Turkey calling for more cooperation with Russia in the fight against terrorism.

A couple of days after Erdogan’s meeting with Putin, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif visited Turkey, where Ankara and Tehran pledged more cooperation — mainly on Syria. Then, the Turkish tone on the Syrian conflict softened and a visit by Erdogan to Tehran was announced. Days later, Russian fighters used an Iranian airbase to bomb rebels in Syria, while Syrian regime forces started shelling Kurdish fighters in Al Hasaka in the north-east. All these fast-moving developments in Syria, along with the fierce fighting in Aleppo led by the Al Qaida-linked Jabhat Al Nusra (now known as Fatah Al Sham) and the America-backed Kurdish militia capturing a town from Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) offer an illusion of the conflict coming to an end.

It’s not the first ‘hype’ over of fighting and political manoeuvres in the five years since the conflict started in Syria. However, what is ‘new’ is the seeming alliance between Moscow, Ankara and Tehran. As pro-regime forces may propagate a change in Turkey’s stance as Damascus comes closer to its main backer, Iran, pro-opposition elements can still see the current developments as an opportunity for more active involvement in Syria that will be in their favour in the end. In reality, both parties may be over-optimistic about that assumed alliance. In fact, it may even end up as just a brief coincidence of interests not lasting for long due to deep-rooted clashes of interests. It actually looks more like a Triangle of ‘Doublespeak’ in the Orwellian way.

First, the goal of fighting terrorism means a different end for each party: Iranians seek the end of all opposition to the regime of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad; Turks seek the end of Kurdish armed groups; while Russians seek the end of militants from Chechnya and Dagestan. Second, the theme of ‘only political solution’ is the way to settle the crisis means: For Iranians, an-all inclusive rule with Al Assad at the top; for the Turks, it means an influential Syrian faction aligned with Ankara, like the Free Syrian Army, and some militant groups (except Daesh perhaps); while for the Russians, it means the decimation of most fighting groups that are opposed to the Al Assad regime and that are classified by Moscow as terrorists. Even the cliche repeated in every statement by all parties involved in the conflict and their backers — “unity and integrity of Syrian territories” — is not interpreted in the same way by the three countries.

Let’s look at the coincidences involving the three players to advance the argument that it’s a fragile Triangle. Iran is the main backer of the Al Assad regime, yet it was willing, a couple of years ago, to accept a compromise in Syria with an alternative to Al Assad, provided that its interests are protected. Turkey, which used to be the main route for Daesh terrorists to receive logistical support, is now suffering a terrorist backlash at home, forcing it to change tactics. Russia, which came into Syria at the height of a perceived American role in the country, is coordinating all its activities in Syria with Washington.

What Moscow, Tehran and Damascus have in common are actually bilateral circumstances. Turkey and Iran may agree, provisionally, to stop Kurdish gains. Russia may agree with Iran to support Al Assad, but not indefinitely. Russia and Turkey are wary of each other. Russia does not want Turkey to gain substantially in Syria, nor does Turkey want Russia to be the dominant power on its borders.

What is most clearly evident here is that the Arab parties concerned are on the margins for now, while regional and international players go on an overdrive. However, such a scenario may not continue for long and a new cycle of the conflict could ensue soon.

Dr Ahmad Mustafa is an Abu Dhabi-based journalist.