Congress can’t be ignored on Guantanamo

In banning transfers of dangerous terrorists into the US, Congress is exercising a legitimate legislative function

In a recent Post op-ed, Gregory B. Craig, former White House counsel, and Cliff Sloan, former special envoy for Guantanamo closure, argued that President Obama has the legal authority to ignore the law and transfer some of the world’s most dangerous terrorists to the United States.

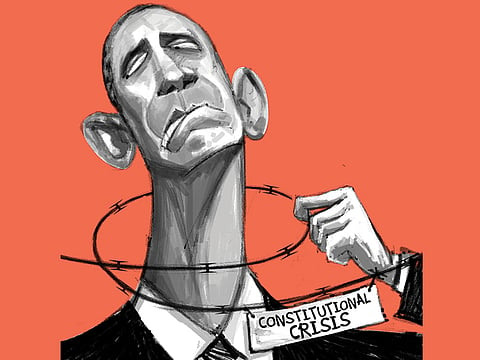

I sincerely hope that, as former Obama administration officials, they are not laying the groundwork for a course of conduct from the White House that can end only in constitutional crisis. In a recent letter, I respectfully requested that the president reject Craig and Sloan’s legal reasoning and assure Congress that he will not transfer detainees from the military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to the United States in violation of the law.

The Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war but reserves to the president, as commander in chief, the ability to “make war”. This led Craig and Sloan to conclude that Congress cannot “direct specific facilities in which specific detainees must be held”.

Stated this broadly, I agree. But in framing the question as “whether Congress can tell the president where military detainees must be held”, they grossly mischaracterised the issue.

Congress has not required that any individual detainee be held in a specific facility. Rather, it prohibited the use of federal funds to move detainees from Guantanamo to the United States. This is not a de facto mandate that the president maintain the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, as Craig and Sloan seemed to assume. It is a legitimate exercise of congressional power to prevent the president from housing some of the world’s most dangerous terrorists on US soil. This, emphatically, Congress can do.

The Constitution’s separation of powers is also a balance of powers. While the president has broad powers as commander in chief, Congress has equally broad authority in its power of the purse and its exclusive grant of legislative powers. The Constitution gives Congress authority to “make all Laws necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the... Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States”. In other words, Congress makes the rules, and the president executes them. Relative to detainees, the Constitution even gives Congress the explicit power to “make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water”. Congress has done exactly that.

Justifiably concerned

In banning transfers of dangerous terrorists into the US, Congress is exercising a legitimate legislative function. We saw with the June escape of dangerous criminals in upstate New York that it is impossible to guarantee Guantanamo Bay detainees will remain confined. Congress has the right to legislate to protect against this risk and to protect the emotional security of Americans who may feel justifiably concerned about living in close proximity to enemy combatants responsible for the deadliest attack on the United States since Pearl Harbour.

Moreover, in United States v Verdugo-Urquidez, the Supreme Court held that the Constitution does not protect non-citizens outside the country. If the president were to unilaterally move alien terrorists into the US, those terrorists could argue for constitutional protections. Congress has the right to protect against this possibility, especially because Congress, not the president, has the authority to determine how and when the domestic criminal laws should be applied.

Craig and Sloan wrote that Congress can pass military regulations, authorise detentions and military tribunals and broadly regulate the treatment of prisoners of war. But for some reason they emphatically denied that it can prevent known terrorists from being transferred to US soil.

In so arguing, they did not mention Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v Sawyer — the seminal Supreme Court decision on the relative powers of the executive and legislative branches of government.

In Youngstown, a labour dispute led to a strike that threatened to close the nation’s steel mills in the midst of the Korean War. President Harry S. Truman believed this would cripple the war effort and ordered that the US government take control of the nation’s steel mills to prevent their closure. In passing the Taft-Hartley Act, however, Congress specifically considered and rejected an amendment that would authorise government seizures in cases of emergency.

Truman’s order was in direct contravention of congressional will, but he argued it was justified because it was necessary to avoid national catastrophe in a time of war. The Supreme Court disagreed.

In a concurrence that has become a foundation of constitutional law, Justice Robert H. Jackson described executive authority as ebbing and flowing in conjunction with congressional will. When the president acts with congressional authority, this power is “at its maximum”. When the president acts in the absence of either a congressional grant or denial of authority, there is a “zone of twilight” where Congress may have concurrent authority. When the president acts against the express will of Congress, however, his power is at its “lowest ebb”.

Jackson presciently warned of the danger of allowing the president to ignore Congress: “Presidential claim to a power at once so conclusive and preclusive must be scrutinised with caution, for what is at stake is the equilibrium established by our constitutional system.”

With these stakes, and against this precedent, Craig and Sloan concluded that the president can and should ignore the expressed will of Congress and transfer the Guantanamo Bay detainees to the US. I disagree. Hopefully, as a constitutional scholar, President Obama does as well.

— Washington Post

Jim Sensenbrenner, a Republican, represents Wisconsin’s 5th Congressional District in the House.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox