Conflict and reconciliation

Relationship between Islamic movements and the US are still shrouded in mystery

Contradictions we face in life are numerous and we try to coexist with them in the extended community and in our smaller family circles.

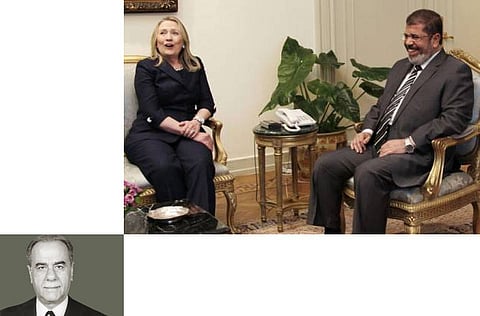

However, the world of politics is filled with controversies. The latest episode took place during US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s visit to Egypt and her first meeting with the new Egyptian President, Mohammad Mursi.

Through media channels, we all witnessed a successful meeting between Clinton and Mursi which was punctuated with lots of smiles and friendly nods.

After the meeting, an Egyptian presidential communiqué was issued, which stressed the strong relations between Egypt and the US, adding that Egypt will honour all the standing agreements and treaties between the two countries.

However, Clinton spent an unpleasant night at her hotel suite in Cairo after angry demonstrators marched from a gathering point near the airport to where she had been put up.

The scene was repeated in a more violent manner the following day as Clinton visited the US Cultural Center in Alexandria.

The controversy here is a bit humorous because Clinton was in fact received by the representatives of the biggest Islamic movement in Egypt — The Muslim Brotherhood — with the newly-elected Egyptian president as a part of this movement. Those who threw stones at Clinton, on the other hand, were a part of the civil liberal movement in Egypt who have always been inspired by the American liberal thought and values.

The US official’s visit is part of America’s keenness to remain aware and alert to any new Egyptian stance towards the Camp David Accords to put the Israelis — whom Clinton visited afterwards — at ease.

It is a fact that the Egyptian public was against the Camp David Accords that were struck by the late Egyptian president, Mohammad Anwar Al Sadat — as a result of which his popularity dropped to its lowest ebb, as did the popularity of former Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, for the same reason.

The nationalists, Islamists and Pan Arabists were all against the normalisation of relations with Israel and they all regarded the Israeli embassy in Cairo with great animosity. Hence, the appearance of an Islamist president in Egypt may re-shuffle the cards in a manner which will annoy the US and its ally: Israel.

There are conflicts and differences between the targets of Islamic movements and their US counterparts. These conflicts are further emphasised by different cultural and traditional affiliations and the stands of these movements regarding political regimes that are either allies or friends with the US.

The differences are also deepened by America’s bias towards Israel.

The relationship between Islamic movements and the US are shrouded in mystery and the only rational feature in these relations is US interests in the region.

Islamic movements around the world have different agendas and some of those do not hide their animosity towards US policies; while others carried their hatred one step further by executing terrorist operations across the globe against western — especially US — interests.

Other Islamic movements — such as the Turkish Justice and Development Party — do not mind becoming part of a secular civil state. The US strategy, on the other hand, is set up on pragmatic lines that place its interests at the forefront. Hence, it utilises a selective policy where it prefers some Islamic movements over others.

The Al Qaida movement has been marked with red and is a group that will be fought against in bitter wars. On the other hand, we find that the US is ready to open channels of dialogue with other Islamic movements despite the fact that these movements carried arms against the US once upon a time and allied themselves with Al Qaida against US interests in the past — such as Talaban.

Since the 1970s, the US was aware of the receding popularity of leftist and Pan Arab movements in the Arab world. It also saw the growing influence of the Islamic powers and movements, especially after the downfall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War era.

US strategists and policy makers made it clear that the coming phase needed a revaluation of some stands and convictions towards Islamic movements — and that is what has happened in fact.

The ascendance of Barak Obama as President of the US was the practical interpretation of this metamorphosis. The US lifted away its backing and cover of all undemocratic regimes since Obama’s famous speech at the University of Cairo in 2009, where he warned governments of the woes of ignoring essential reforms.

The US did not hide its sympathy for the masses that carried banners, calling for reforms and change in a number of Arab countries, despite the fact that their governments were US friends and allies.

True, the US did not contribute openly to the change that took place in Egypt, which paved the way for the Muslim Brotherhood candidate to become president, but it’s important role in all that change cannot be overlooked.

The US may find it unlikely that the new Egyptian president will follow a different foreign policy than the one exercised by the former regime because the political atmosphere in the Arab World now is different from what it was in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

It will also be difficult to surpass establishments such as the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Add to that the fact that the Egyptian economy is unable to sustain itself without the annual aid received from the US.

It will not be easy for Egypt’s new president to ignore the size of the opposition he will face with every political step he takes — as half of the voters had voted for his rival, belonging to the military establishment — and calls for a civil state.

Dr Mohammad Akef Jamal is an Iraqi writer based in Dubai.