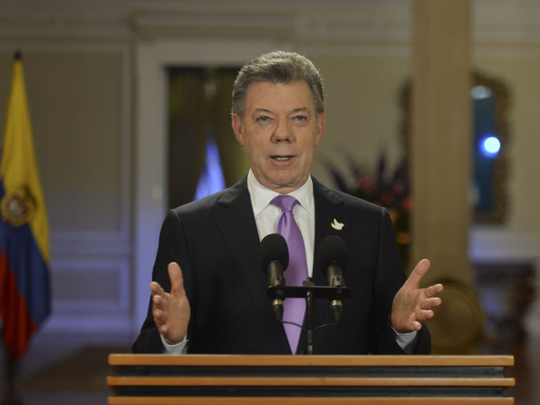

No one has ever accused Juan Manuel Santos of aiming low. The Colombian president already has staked his career on peace talks to end Latin America’s longest-running guerrilla insurgency, a chimera that eluded half a dozen leaders before him, almost cost him reelection and split the country nearly in two. Last week, Santos raised the stakes again, announcing a halt on air strikes against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) — a roll of the dice that could conceivably land him a Nobel Peace Prize or cashier him off into the Andean ether.

The March 10 announcement surprised Colombians and everyone else, following the contortions of the drawn-out parley between the Santos government and the Farc. It was only a pause, said Santos, not a truce — government troops captured a top rebel commander on Friday — and he pledged to review the order in 30 days.

After all, the Farc had declared a unilateral ceasefire last December and kept their word since, Santos claimed.

Nonetheless, the move contradicted his pledge that suing for peace was no sop to the insurgents and that Colombia’s security forces would carry on their offensive until the last guerrilla had fallen or surrendered.

The turnabout is a signal that the 28-month peace process has ground forward — though Friday’s blast from an improvised explosive device that injured eight people in Bogota seemed to have shaken that conviction. Negotiators in Havana since late 2012 have pencilled agreements on three articles: Countering drug-trafficking, land reform for struggling farmers and allowing decommissioned guerrillas to take part in electoral politics.

Still on the table are the delicate issues of reparations for victims of the 51-year-old conflict and making sure repentant guerrillas pay for their crimes, plus the sticky matter of getting the Farc to give up their guns. Government and rebels recently agreed to start clearing land mines.

Another quandary is reeling in top combatants wanted on extradition orders by the US, Colombia’s closest international ally. That may explain why the Obama administration named Bernard Aronson, a Latin America hand with experience in peace deals, as special envoy to the Havana talks. “Santos’s main goal is a peace agreement,” said Michael Shifter of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based think tank. “Giving up extradition may be the price of the deal, and that’s probably what Aronson is there to say.”

Shifter sees Santos driven to wrapping up the talks this year. “Santos has staked his whole presidency on this,” he told me.

Wooing guerrillas is not Santos’s only gamble. Until all articles in the plan are agreed upon there is no peace and even then the whole deal must be submitted to the Colombians in a referendum. And there the battle rages.

Recently, Colombians have warmed to the peace effort, with 53 per cent saying in a Gallup poll earlier this month they had faith that the talks were leading to peace. But Santos’s approval ratings have tumbled with Colombia’s economy, which has slid in turn with global oil prices. And he must still defend himself from a rump of contrarians. Leading the pack is former president Alvaro Uribe, one of Latin America’s rare conservative caudillos, who hired Santos as defence minister and then groomed him as successor, but hoped for an avatar. Still hugely popular for his war without quarter on the Farc, Uribe never forgave his former protege for extending an olive branch to the insurgents and now snipes at Santos relentlessly on Twitter to 3.6 million followers. “Santos squandered his inheritance and doesn’t realise it,” he tweeted.

Santos at first turned the other cheek, but soon was firing back in “a scandalous spectacle”, in the words of Colombian opinion writer German Uribe (no relation to the ex-president), that has so polarised the country, “even the most sensible among us, who believe in a peace accord” now wonder “if it could last”.

Santos has poured his heart into ending Latin America’s longest shooting war. Winning the peace may take even longer.

— Washington Post