Ten years ago, Indian economist and politician Jairam Ramesh coined a word that captivated pundits and investors: “Chindia.” The idea that China and India may join forces, to cooperate as much as they compete, was both seductive and fleeting. Observers were heartened by promises from the then-Chinese president Hu Jintao and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to enact sweeping internal reforms and embrace regional cooperation — neither of which happened. The leaders of the world’s most populous nations turned inward. Their domestic problems festered.

Now that Beijing and New Delhi are in the hands of Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi, respectively, both self-described reformers, could “Chindia” finally come to fruition as a force for mutual prosperity? Xi and Modi should certainly try, even if the obstacles standing in the way are formidable.

No less than India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had entertained this same dream 70 years ago, when he predicted that an independent India and China would join the US and Soviet Union as the post-war’s dominant world powers. Sheer size seemed to guarantee their global influence. Now, though, the focus for both China and India must be on shared interests and economic ties that recognise relative strengths and weaknesses.

Sorting out those shared values is a prickly business, of course. China’s close relations with Pakistan irk New Delhi, while Modi’s budding friendship with Japan’s nationalist-in-chief, premier Shinzo Abe, makes Beijing wary. In his election campaign, Modi promised a harder line on protecting India’s borders with China, where troops have clashed in recent years. US President Barack Obama’s “Asia pivot” also is a potential dealbreaker if Washington tries to divide India and China to maintain its sway in Asia.

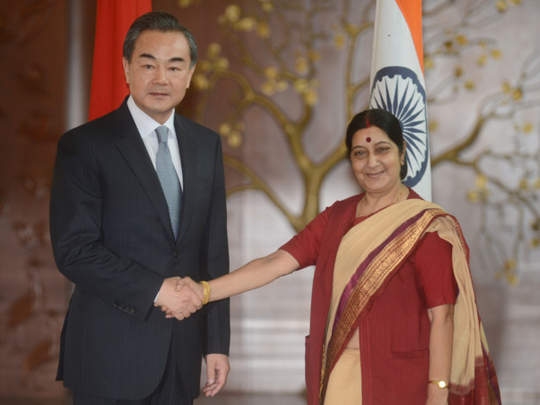

However, “Chindia’s” vast potential is reason enough for Xi and Modi to make building mutual trust a priority. That process began in earnest last week when Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj met her Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in New Delhi. At issue was unleashing the huge untapped trade potential between the two countries. With a combined annual gross domestic product (GDP) of more than $10 trillion (Dh36.78 trillion), their trade of $49.5 billion in the April-December period really is a pittance.

The immediate onus is on Modi. There can be no doubt India’s development model lags behind China’s. Consider that the headlines Ramesh makes these days are not about grand economic unions, but toilets. Until Modi’s victory, Ramesh was rural development minister, a role in which he grappled with the shocking fact that half of India’s 1.2 billion people still defecate in the open. He even once implored women not to marry into families that did not have toilets. Modi pledges to put one in every home. Meanwhile, as New Delhi tends to plumbing, Beijing is signing $400 billion gas deals with Russia and building new skyscrapers.

Yet, think of the possibilities. China’s coastal cities may be booming, but its underindustrialised hinterlands can use a serious jolt. How about jointly operated special-enterprise zones that employ a mixture of workers from both nations? Along with cutting red tape, India’s most immediate need is for new roads, ports, bridges and power grids so that it can better compete globally. China’s deep pockets can help finance such a building spree, while its companies can help pour the concrete.

This is not about altruism, but complementarity. India wants to raise manufacturing’s share of GDP (which lags far behind Thailand and South Korea, never mind China) and Beijing wants to go upmarket. As China moves away from low-end manufacturing (which India covets) and towards a more entrepreneurial economic model (which India has), it could do worse than share notes and strategies with India.

We tend to obsess about the differences between China and India. Beijing’s ability to get things done sets Asia’s No 1 and No 3 economies apart by a wide margin. India’s respect for free speech offers quite a contrast to China’s counterproductive fear of Facebook, Twitter and the New York Times.

Yet, the two countries also share many challenges: Huge and growing divides between the rich and poor; rampant corruption that squanders growth; runaway pollution; insatiable appetites for energy and other commodities; public debt levels that worry the outside world; a preference for boys that is wreaking havoc with demographic trajectories; religious tensions; a distrust of western institutions and discredited “Washington Consensus” policies; and powerful bureaucracies doing their worst to make sure nothing changes.

One important caveat: Both nationalists, Xi and Modi must avoid buying into the hype about what joining forces could achieve. If this ends up being another Xi-Vladimir Putin exercise in nose-thumbing at the West, the enterprise may fail. It is not in democratic India’s best interests, security-wise or financially, to make an enemy of Washington.

But Xi and Modi would be wise to try to make “Chindia” an economic reality. It will not just benefit their 2.5 billion-plus people, but the entire global economy, too.

— Washington Post

William Pesek is a Bloomberg View columnist based in Tokyo who writes on economics, markets and politics throughout the Asia-Pacific region.