Until recently, Arab academics and policymakers had only a limited interest in China, in contrast to other great powers on the world stage. This disarray was due in large part to the fact that China remained an impoverished and agricultural country in the Third World, despite its possession of nuclear weapons in 1962.

The tide turned with China’s open-door programme and accompanying period of modernisation under Deng Xiaoping, which began in 1978. By 2015, China’s total gross domestic product was $10.4 trillion (Dh38.25 trillion), making its economy the second-largest globally, racing ahead of Germany, the United Kingdom and Japan. Assuming that Beijing will be able to overcome its present-day economic and financial troubles and return to the rates of economic growth to which it had become accustomed — around 8 per cent per year — then it can expect to equal the US in terms of the size of its economy by 2035. Despite this, China remains vulnerable on a number of fronts. This includes the country’s reliance on foreign markets and on the consumers overseas who buy its products. It also includes China’s dependence on sources of energy that are located in areas either controlled by western powers or within the sphere of influence of those powers.

Today, China imports two thirds of its oil from the Middle East, thus explaining Beijing’s desire for good relations with the oil-exporting Arab states, particularly Saudi Arabia, in addition to Iran. This has been paralleled by a growing realisation among policymakers in both Riyadh and Beijing of the large extent of common ground the nations share. These realisations come in parallel with a string of events that have shaken Saudi faith in the alliance with the United States. Riyadh has even undertaken to guarantee sufficient and permanent oil supplies to China, paving the way for Chinese investments in the oil sector and other industries in Saudi Arabia. In concrete terms, Riyadh already meets 17 per cent of China’s demand for oil and has offered to help China consolidate its strategic oil reserve, with a projected capacity of 500 million tonnes. Efforts to create joint ventures between Chinese and Saudi industrial giants are already under way, with Sinopec and Saudi Aramco cooperating to construct oil refineries in the Fujian Province and the coastal city of Chengu and an industrial mega-complex to produce petrochemicals.

For the US, any signs of Saudi-Chinese cooperation in the energy sector and in petrochemicals could be an indicator that it stands to lose influence in one of the most vital regions of the world. Equally, Iran views the growth of relations between China and Saudi Arabia with trepidation, since such ties could result in greater Chinese understanding of Saudi and Gulf Cooperation Council worries of Iran’s growing military capabilities, in which China is a major partner. Sino-Iranian military cooperation has a solid foundation, and covers certain essential areas such as long-range ballistic missiles. Beijing is also a supplier of military technologies, including anti-ship missiles, to Iran. Additionally, Iran’s role as an energy supplier with access to offshore oil-and-gas fields in both the Gulf and in the Caspian Sea, as well as its role as a country with accessible land routes that could bypass hazardous sea lanes, has made the country vitally important to China.

In order to protect its oil network against a variety of threats, including piracy, China has had to bolster and expand the presence of its naval forces in and around the Gulf. This has brought Chinese military vessels to the Rimlands of the Arab region, to the Indian Ocean coast and to the Horn of Africa, where its on-land interests can be found in Sudan and Ethiopia.

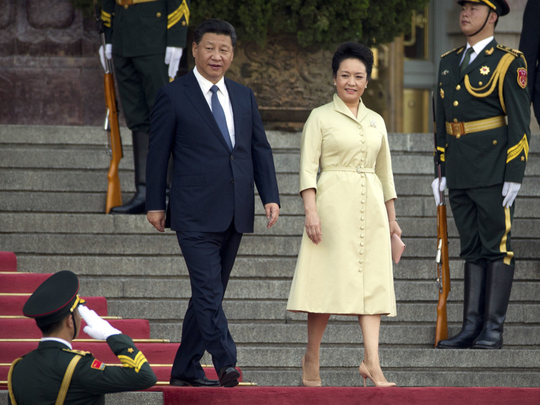

Beginning in 2013, China’s President, Xi Jinping — inspired by the Silk Road of antiquity — unfurled the “One Belt; One Road” initiative, which envisages the emergence of three important trade routes, including maritime shipping lanes that will link China to the Arabian Peninsula, the Mediterranean via the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. The “Belt and Road” project will see the rolling out of vast paved roads and railroads, as well as other vital infrastructure projects that will guarantee the smooth flow of cargo over land, sea and air. The project will also provide for the security of oil and gas pipelines and the construction of transnational power grids.

While this Chinese venture seems bold and ambitious, and will likely face massive challenges, the Belt and Road also represents China’s best hope to solve some of its long-standing and deep structural problems, including its surplus production capacity and weak domestic demand. This is coupled with the stalling in Chinese exports to the West as a result of increasingly protectionist trade policies by western governments. Thus, the Belt and Road offers a chance to think of the possible growth and expansion of Sino-Arab strategic relations. If successful, the expansion could also liberate the Arabs from their exclusive reliance on the West for a host of political, economic and security issues.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is a Syrian academic and writer.