If there’s one thing on which Europeans agree with Donald Trump, it’s that the US is gradually losing to China. The Middle Kingdom is working hard to improve its image in Europe and investing lots of money along the way. The queen of England may think Chinese officials are “very rude,” but outside Buckingham Palace they are winning influence and friends.

In 2015, a Pew Global Research survey found that a majority of people in major European countries believe China is going to replace the US as the global superpower or that it has already done so.

The same study showed that in Germany and France, more people consider China, rather than the US, to be the world’s leading economy. That was before China’s recent economic troubles began, but those probably won’t affect public perceptions greatly: China’s size and the prevalence of Made-in-China goods in European stores — where US ones are hard to find — will continue feeding this somewhat premature perception.

None of this appears to make Europeans particularly happy. On the whole, they still mistrust China more than they do the US. According to Pew, 83 per cent of Italians and 50 per cent of Germans have a favourable view of the US, compared to 40 per cent and 34 per cent with a favourable view of China. Even so, those perceptions have been changing in recent years.

The jump in positive perceptions is, in part, explained by greater exposure to Chinese people. The number of Chinese tourists in Europe doubled in the last four years. Half of them were millennials — people who have more in common with Europe’s younger generation than their parents did with their peers. They are more freedom-loving, more hedonistic and easier to like.

Then there are the Chinese immigrants. They were the second biggest group of newcomers to the EU last year, after Indians — not counting refugees from Middle Eastern war zones. Small neighbourhood stores from Prague to Lisbon are, as often as not, run by Chinese immigrants, hardworking people who keep trading long after everybody closes.

And then there is the Chinese money coming in — more of it than ever before. Europe is the priority area for Chinese direct investment. Last year, Chinese firms poured a record $23 billion (Dh84.4 billion) into the EU, against $15 billion in the US.

Overall, US investment in Europe is still much more plentiful. Last year, it exceeded $193 billion, according to the US Department of Commerce. Yet in some countries, Chinese investors have been more active than American ones.

More tolerant

In Italy, for example — the country that has seen the biggest jump in China favourability — the Chinese contributed $7.8 billion to the economy, compared to just $434 million from the US. France, too, saw more Chinese than American investment.

Most of the Chinese money goes into real estate, the hospitality industry and infrastructure. It makes sense that it tends to flow into the same countries favoured by Chinese tourists, but there’s more to it than that. Asian investors are more at home than Americans with convoluted, sometimes illogical regulation and the corruption that often accompanies it. That may explain why Chinese investors are most active on Europe’s periphery, where US business is less interested in going. Portugal is one of the preferred destinations. There has recently been a spate of big Chinese acquisitions in the energy, insurance, tech and food industries, and Chinese businessmen are the biggest beneficiaries of Portugal’s popular investment visa programme.

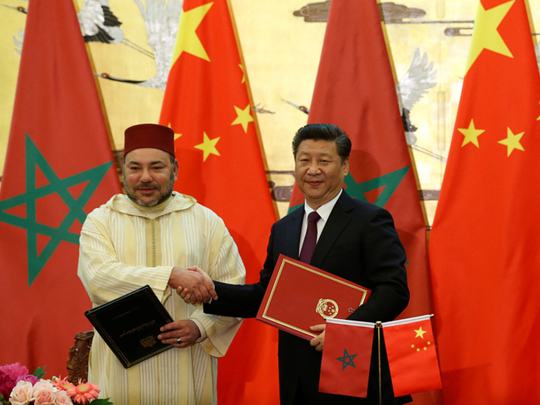

Peripheral, hard-up EU nations are also more tolerant of investment by Chinese state-owned companies, which accounted for 70 per cent of last year’s inflows. That, in part, explains why Chinese diplomatic efforts have lately focused on Eastern Europe. In March, President Xi Jinping visited Prague to discuss, among other things, big investments in infrastructure projects that would link China’s new ‘Silk Road’ transport corridor — Xi’s pet project — to central Europe.

In late June, Xi is coming to Belgrade. Serbia is only an EU candidate, and not the most diligent one, but that only makes it easier for China to make inroads. State-owned Chinese companies have been building bridges and power plants in Serbia, investing in the kinds of projects that build goodwill and cause no resentment.

As China expands its influence into the Western world, Europe is far more receptive than the US.

“Europeans are more conflicted and generally less negative in their feelings toward China than Americans because there is less of a great power rivalry and some also feel the need at times to distance themselves from US-led initiatives,” Yukon Huang of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace wrote in a recent article.

Although the US is still perceived as the more natural ally, China’s patient drive for acceptance in Europe is beginning to pay off, especially in the needier, weaker parts of the continent. It’s not a big problem that the queen doesn’t care for Chinese bureaucrats: They’ll keep coming back.

— Bloomberg

Leonid Bershidsky is a Berlin-based writer.