China is bent on world domination — not with its missiles and aircraft carriers, but by controlling solar energy, cloud computing and other industries of the future.

That is an only slightly exaggerated version of a warning coming from the American chamber of commerce in China. It sent a delegation to Washington last week to warn that “China’s aggressive mercantilist policies are one of the most serious threats facing the future of US advanced technology sectors,” as their policy paper says — and that the US government isn’t doing enough to counter the threat.

The warning is especially startling coming from AmCham China, as it calls itself, which for years flexed its advocacy muscle persuading the United States to let China into the world trading system and rebutting Americans who it felt were too hard on China.

“Now we’re saying that things are really lopsided, and the government needs to wake up and take action,” James McGregor, chairman of APCO Worldwide in China noted. “This is aimed at domination of the industries of the future. We’re talking about artificial intelligence and all the things that are important to the American economy.”

Given US President Donald Trump’s anti-China rhetoric during the campaign, you might expect US executives in Beijing and Shanghai to feel optimistic about the prospects for a US response. They are hopeful — but they are also nervous, for reasons I’ll get to in a minute, that the administration may miss this opportunity to course-correct.

First, though: Why has AmCham changed its tune so dramatically since the upbeat days of China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation?

The chamber’s response: China has changed, not us. Its policy has shifted, from “reform and opening” to “reform and closing”. The Communist regime still wants economic growth and market mechanisms, in other words, but without subjecting its economy to open competition from outside. In fact, a recent survey showed that more than 80 per cent of the chamber’s members “feel less welcome than before,” Lester Ross of the WilmerHale law firm, opined.

China has a well-developed, long-term industrial strategy. It limits US firms’ access to its market; demands that American companies share their advanced technology to get even that limited access; buys foreign companies that possess technology it needs while preventing US firms from investing in China; shovels resources to Chinese companies as they ramp up; and then, once those Chinese firms have fattened on the vast and protected Chinese market, sends them out to compete in the world.

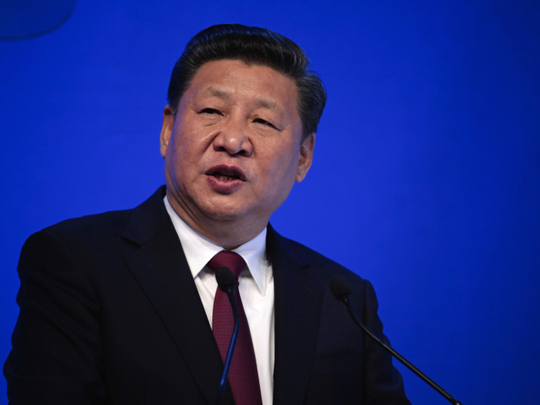

Since meeting Chinese President Xi Jinping, Trump has seemed very taken with the Communist leader and the budding US-China relationship, which he described as “something very special, something very different than we’ve ever had.”

This could be a prelude, US executives worry, to economic concessions designed to win cooperation on North Korea. They also worry that, to the extent the administration remains focused on the economy, it is on iron, steel and other heavy manufacturing sectors rather than technologies that will be crucial in the future.

Most of all they worry, though, because it wouldn’t be easy for anyone to come up with an intelligent response to the uneven relationship.

“Our systems are fundamentally different,” explained Timothy Stratford, who worked in the US trade representative’s office from 2005 to 2010. “We follow process... China is focused on outcomes.”

If US law allows a Chinese company to buy an American one, in other words, the US government isn’t going to interfere — even if US firms are being blocked in China and the overall situation seems unfair.

Several industry leaders have called for new levels of review for proposed Chinese investments. Mostly they want a recognition that the Chinese economy is not operating as Americans hoped it would during the push to open the global trading system — and that waiting for it to “evolve” is no longer a viable option.

“The solution has to be some combination of offence and defence,” said Randal Phillips, Asia managing partner for the Mintz Group. “China has to face some consequence.”

— Washington Post

Fred Hiatt is the editorial page editor of The Post.