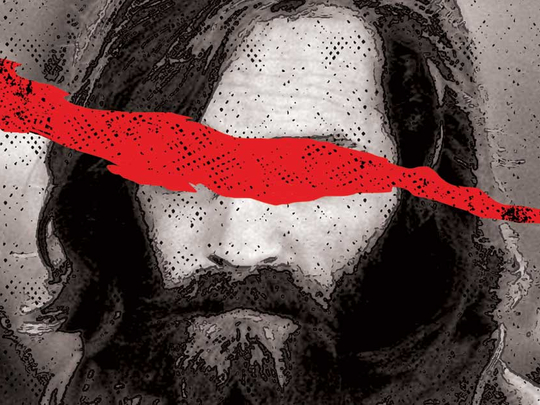

Charles Manson is finally dead. There is no resting in peace for such a person. At his trial, Manson told the prosecutor, Vincent Bugliosi, that he was already dead. He had said previously that he had been dead for 2,000 years. This was part of the confused allusions he made to being Christ. The terrible murders he committed in 1969 and his courtroom testimony transfixed America. The cult leader was finally starring in his own movie, strutting and fretting his hour upon the stage — a short, long-haired man full of violence, rage and manipulation.

Now if you care to look on the internet, Manson’s ramblings are memorialised on various websites, like inspirational quotes complete with images. The court could not break him, but then he had been broken and killed many times over many years ago, he claimed. There was some truth in it, although not the whole truth. Never that. These quotes may not be inspirational, but they remain influential: The killer as the apotheosis of alienation, a strange object of admiration. Now that he really is dead, will his influence — if he really was anything other than a con man, a paranoid schizophrenic — live on in our culture? His name itself is a shortcut to some edgy, wicked outsider mentality (Marilyn Manson, Kasabian, the band calling itself after Linda Kasabian, a member of Manson’s cult). In interviews conducted in his later years in prison, where he says spiders he fashioned out of the yarn of his socks allowed him to control the world, he comes across as old, pathetic, bewildered, mentally ill. These are what people should take a look at. Yet, at the time of the murders, the details of which are still so absolutely shocking — the X cut on Sharon Tate’s pregnant belly — the culture was still strangely ambivalent about Manson.

He appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, with a headline asking if he was the most dangerous man in America. Rock star murderer? The myths abounded: He had an audition for The Monkees (this is doubtful); he communicated to his followers in prison telepathically, as they all carved swastikas on their foreheads the same day. Then there is the ongoing argument that he didn’t actually murder anyone himself, he just got them to do it instead.

The reality was both more prosaic and ugly. He had been in and out of prison all his life, where he learned to be abused and how to abuse — he actually asked to stay in prison knowing he was unfit for life outside it but the plea went unheeded and he became a pimp, a thief offering suburban girls drugs and his psychopathic version of family.

Having already been rejected by mainstream society he was also rejected by the counterculture, and could not make his way in the music scene. His anger and sense of omnipotence gave him some kind of charisma. His overriding fantasy was of a race war. He was a loser who would become a winner and he would do it through white supremacy. The thing he called Helter-Skelter would ignite this war. This was the rationale for the slayings. It was a holy war then against the rich and the powerful. The racial aspects seem to me to be forgotten by those who sought to understand him and who gave him the attention he craved. Dennis Hopper, for instance, went to see him in prison, and film director John Waters attended the trial.

The Manson murders were seen to represent the end of the counterculture — peace and love giving way to brutal murder. But parts of the culture turned Manson into a strange kind of idol.

When Joan Didion wrote about this in her 1979 essay ‘The White Album’, she recounts hearing of the murders at Roman Polanksi’s house on Cielo Drive. The numbers of dead were not yet finalised, but there was talk of black masses and bad trips, hoods and chains. She said: “And I also remember this and wish I did not: I remember that no one was surprised. And. At a stroke, the ‘60s ended — the paranoia was fulfilled.” Celebrity and fame were no protection against the darkness, and Didion describes the unease everywhere. She recalls too how she helped Kasabian, who testified against Manson’s group, find a short green velvet dress to wear for the trial.

This is a long, long time ago, but the mythology around Manson and his cult never quite goes away. His songs, such as they are, have been recorded by Guns N’ Roses, Marilyn Manson, of course, and GG Allin, among others. What truths do they tell? He has been interviewed in prison, and movies have been made about him. Most killers do not get this sort of treatment, let alone purveyors of white supremacism.

His death comes though as his pernicious beliefs in a race war have entered the American mainstream. His warped logic holds sway at the highest levels of American society. Was he evil or crazy? Or was he in fact a product of a system that has not changed in all these years. When he said in court: “My father is the jailhouse. My father is your system ... I am only what you made me. I am only a reflection of you,” he told America something. And it was awful. He died an old pathetic and disturbed man. A banal monster. Nothing special. Remember that — and his victims.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Suzanne Moore is a Guardian columnist.