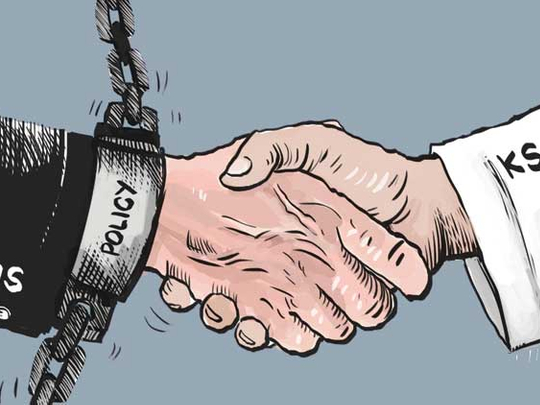

“A true relationship between friends is based on sincerity, candour and frankness rather than mere courtesy,” declared Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al Faisal as he welcomed US Secretary of State John Kerry in Riyadh, clarifying that “the historic relationship between the two countries has always been based on independence, mutual respect, common interest and constructive cooperation on regional and international issues to serve global peace and security”. Although both men aimed to calm a nascent rift, which was clearly accelerated by recent American revisions of long-standing policies towards the Arabs World, fundamental differences were brought to the surface that, left unattended, threatened to fester.

In the event, it was increasingly clear that “strategic” and “enduring” ties between the two countries were frayed by Washington’s confused policies towards the post-2010 Arab uprisings, which altered existing relationships. Nevertheless, what irritated Riyadh most were the Barack Obama Administration’s choices to re-engage Iran over the latter’s nuclear programme and, most important, over its newly found flexible initiatives vis-a-vis Syria.

Naturally, senior state department officials played down these differences, with Kerry underscoring that there were none on substantive questions, even if alternative perspectives existed on key matters. Under the circumstances, Saudi leaders were left perplexed since the logical conclusion of ongoing wishful talks would not prevent Tehran from building nuclear weapons or for Damascus to tame its killing machines. Moreover, and while the US Secretary of State insisted that Washington had neither “the legal authority nor desire” to intervene militarily in the Syrian civil war, Prince Saud Al Faisal insisted that “reducing the Syrian crisis to merely destroying chemical weapons ... won’t help put an end to one of the greatest humanitarian disasters in our times”.

Profound differences aside, both sides recognised that US-Saudi ties were valuable and, equally important, mutually beneficial. For more than eight decades, Saudi officials practised “sincerity, candour and frankness,” while successive American representatives recognised that the Kingdom played critical diplomatic roles throughout the world. That was the reason why few were surprised to hear Kerry describe Saudi Arabia as the “senior player” in the Arab world.

Yet, beyond such platitudes, King Abdullah Bin Abdul Aziz was reportedly unhappy that the Obama Administration drifted away from the US President’s June 4, 2009, Cairo speech. By pursuing policies that many perceived as being the antithesis of lofty sentiments to rekindle American relationships with the Muslim World, especially towards Iran and Syria, Riyadh’s concerns about a US-Iran rapprochement, or the promotion of peace talks over Syria that could leave the pro-Iranian Baath Party and President Bashar Al Assad in power in Damascus, grew exponentially.

In fact, while Riyadh understood and welcomed the US-led P5+1 efforts to try to resolve the dispute over Tehran’s nuclear programme, the King and his advisers displayed far more foresight than anyone along the Potomac. They clearly understood that a nuclear Iran was increasingly likely that, in turn, would necessitate regional parity at great costs. It was this ideological challenge that preoccupied Saudi leaders, anxious to avoid renewed Sunni-Shiite confrontations. Likewise, the Saudi ruler appreciated the financial burden that an arms race would engender and that would derail his priorities — to reform the Kingdom’s institutions and accelerate the country’s development projects.

Of course, Kerry went out of his way to assuage the monarch that the US would not allow countries like Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt to be “attacked from the outside,” which was a code word that referred to Iran, and that no one ought to doubt US security commitments. He proposed to strengthen ties between Washington and Riyadh even further though it was not clear whether he met with the Saudi intelligence chief, Prince Bandar Bin Sultan — whose confidential revelations a few weeks ago to European diplomats that his country would be making “a major shift” in its relations with the US — to iron differences out and, perhaps, to salvage what could be.

Irrespective of any reservations he may have detected in Riyadh, the American diplomat noted that his conversations with King Abdullah were very candid and though Saudi Arabia was proven “an indispensable partner” [his words], Washington realised that the counterpart had “independent and important views of its own,” which the US respected. This was a truly amazing declaration for it illustrated what ailed ties.

True to his character, one must assume that the Saudi monarch informed Washington that the Middle East peace process, the civil war in Syria, the rise and fall of extremist religious groups in Egypt and elsewhere, ongoing tensions in Yemen and Lebanon and, especially, developments in Iran, required true leadership, which he could no longer distinguish in his American counterpart.

He probably stressed the need for Washington to abandon its lukewarm support to the Egyptian Government as Cairo moved to restore order before adopting a constitution that embarked on democratisation instead of stifling it to serve extremism. Similarly, the King was adamant that Al Assad ought to play no political role in the transitional phase and that the true representatives of the Syrian nation were those serving in the Opposition Coalition. Although Washington preferred a negotiated political solution, if possible in a process like Geneva 2 because such a settlement could ostensibly prevent violent extremist groups from coming to power, neither the joint UN-Arab League Special Representative Lakhdar Brahimi nor Russia, nor anyone else for that matter, managed to stop the fighting. The King must have reminded Kerry that it was not enough to say “Al Assad has lost all legitimacy and must go”, but that the time was ripe to show him the door.

Kerry ended his visit by reiterating the American position on Iran, namely that the US would not allow Iran to acquire a nuclear weapon, though his laudable diplomatic preferences to resolve this challenge bordered on the fantastic. Saud Al Faisal dug deeper and raised the question of Iranian intentions as Tehran worked in earnest to acquire a nuclear capability, which begged the question: How could US-Saudi ties return to normal when Washington opted to play the field?

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is an author, most recently of Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia (Routledge, 2013).