With the White House reportedly trying to negotiate a 10- or 15-year deal on Iran’s nuclear programme, Republican leaders in Congress are threatening to unravel the agreement much sooner — during President Barack Obama’s final months or soon after he leaves office.

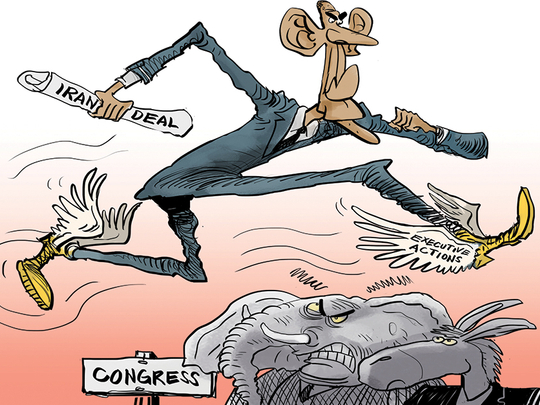

According to several news reports based on leaks from inside the negotiations, the pact being offered to Iran eases restrictions on its nuclear programme and relaxes sanctions on its economy in several phases over at least a decade. Since Obama does not intend to seek the Republican Congress’s approval for any deal, fearing it would be rejected, he would instead use executive actions, national security waivers and his powers to suspend any sanctions that Congress won’t repeal.

While Obama could possibly run out the clock until 2017 in this way, the next president may not be able or willing to use these tools. And if that next president is a Republican, he or she likely will have run a presidential campaign based on opposing the deal.

This puts the White House negotiators in a bind: Unless the administration can make a convincing case that any deal Obama offers can survive well past his time in office, the regime of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is unlikely to buy into the phased approach being offered by the so-called P5+1 countries.

“The supreme leader has said publicly that he is concerned that if he enters into an agreement that the very next president is going to change that agreement,” Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker told Bloomberg reporters at a breakfast last Thursday.

How, then, can the White House possibly persuade Tehran that this deal can outlast his presidency? Corker said he thinks the administration will likely make the case that by the time Obama is gone, the momentum of the deal will have set in and the international sanctions regime will have crumbled beyond repair, tying the next administration’s hands.

“They believe everything falls apart at that time. I think that’s what they are selling to the Iranians,” said Corker, who is working on a bill with Senator Lindsey Graham to mandate a Congressional vote on any nuclear deal with Iran.

While it’s unclear whether the Iranians will buy that argument, Corker certainly doesn’t: “If they went through this process where they actually brought it to Congress and Congress passed muster on it, it really would be a much more settled issue.”

Most Republican congressional leaders, and some Democrats, agree that Obama is making a mistake by avoiding Congressional participation. John McCain, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, told me the administration is leaving itself and its successor open to several actions by trying to skirt Congressional oversight.

“I don’t think the next president is bound by it if it is only an agreement and not a formal treaty,” McCain said of any nuclear pact. “To allege that this doesn’t have all of the marks of a treaty is an insult to everybody’s intelligence.”

Pushing for a better pact

Graham told me that he preferred working to push the administration to negotiate a better pact now as opposed to working to change it after it is signed.

“To begin a bad deal is a nightmare. Once you set the process in motion it’s very hard to change it,” Graham said. “I don’t like the idea of managing a bad deal, I want to stop it. And I have no desire to stop a deal that achieves the objectives.”

Other congressional Republicans, however, have little interest in cooperating with the White House, even to the point of telegraphing to Iran their hopes to scuttle any pact sooner or later.

“If the deal is not submitted to Congress, I and many others will make clear that Barack Obama will be in office for 23 months and I will be in office for six years. And the Iranians should take that into their calculation as they negotiate with Barack Obama’s team,” one Republican lawmaker told a group of reporters one Wednesday in a round-table discussion held on a background basis.

Experts who support the White House’s Iran negotiations say such threats are largely bluster, and that if the Obama administration is able to reach a deal with Iran now, it will be very hard for the next president to stand against it. “If you are planning something two years down the road, you can do all the planning you want, but it means very little because who knows what the situation will be then,” said John Isaacs, executive director of the Council for a Livable World.

After all, said Isaacs, the next president wouldn’t just be derailing a US-Iran agreement, but undoing the work of seven countries, including close US allies such as Britain and Germany. If a deal is working at least reasonably well until 2017, and the Iranians are mostly complying, efforts to change or repeal it would risk putting the US and Iran back on a path to war — or at least that is the argument the pact’s supporters will make. Mark Dubowitz, the executive director of the Foundation for the Defence of Democracies and a sceptic of the nuclear negotiations, said he thinks Congress probably won’t even wait for the next administration to try to thwart any Iran deal.

Terrible miscalculations

“The Obama administration is badly miscalculating in believing that it can unilaterally provide durable sanctions relief without congressional buy-in,” he said. “There are many ways that a creative Congress can make it difficult to implement a bad agreement on which they were sidelined.”

Along these lines, some Republican House leaders, including Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Ed Royce, are working on a new Iran-related bill crafted to thwart Obama’s implementation of any deal this year and next, according to Dubowitz. Among other things, the legislation would take away the executive branch’s national security waiver authority, remove the Treasury Department’s flexibility to issue licences for companies to do business with Iran, and make it harder to undo sanctions designations now on Iranian banks. The Senate, meanwhile, is working on a new sanctions bill crafted by Republican Mark Kirk and Democrat Robert Menendez. The legislation would automatically impose new punishments on Iran if no deal is reached by this summer’s deadline or if Iran is seen as not living up to its end of the bargain.

The Senate is waiting to act on the Kirk-Menendez bill until after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addresses Congress this week, Corker said.

So this is where things stand now: Republican leaders such as Corker want to assert Congress’s role in foreign policy while also working constructively with the administration; other Republicans simply want to kill the deal; most of the Republican presidential aspirants are certain to criticise the administration’s approach; and presumptive Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton is likely to cautiously back any Iran deal but not claim ownership in case it smells bad by the time the election comes about.

As if getting Iran to agree on a nuclear deal wasn’t a big enough hurdle for the administration, it now seems certain that locking in a pact will simply mark the start of another battle with Congress. Obama can probably keep Republican efforts against him in check while he is still president, but after that, all bets are off.

— Washington Post

Josh Rogin is a Bloomberg View columnist who writes about US national security and foreign affairs.