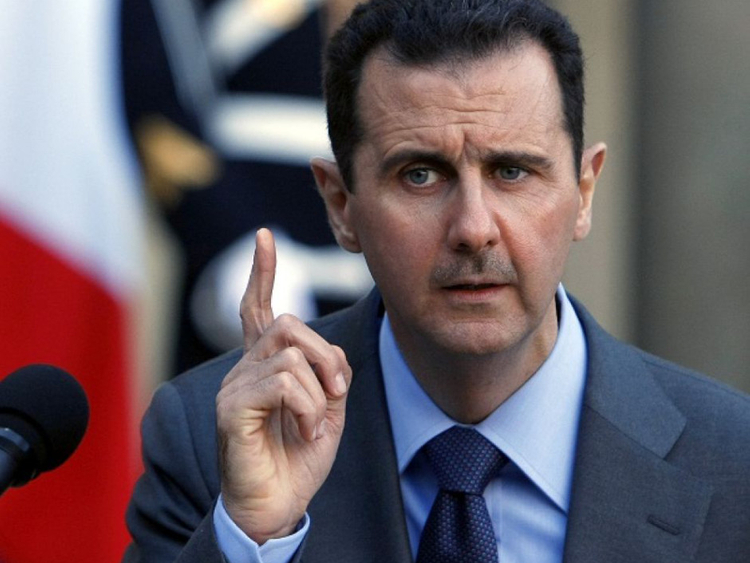

When US President Barack Obama scuttled away from his red line on Syrian chemical weapons attacks in August 2013, he sacrificed his strategic goal — removing Syrian President Bashar Al Assad — for a tactical gain: eliminating Damascus’ chemical weapons stocks. In the meantime, more than 150,000 Syrians have perished, millions more have been displaced, and Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) has metastasised.

The deal effectively cemented Al Assad’s position in power by removing the looming threat of direct US military intervention, so long as the dictator could deal with his local enemies. Al Assad solved that problem by turning to the Russians. Thus, the red line debacle also reversed forty years of American diplomatic successes in pushing Russia out of the Middle East and opened the door to a massive increase in Moscow’s political and military influence there.

But at least Al Assad could no longer threaten his neighbours and terrorise his population with nerve gas and blister agents. The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg recounts Obama’s thinking: “Not only was this not a screw-up, as is commonly understood, but it’s actually for him a very proud moment, because he did something without war, that could not have been achieved with war.”

The only problem with Obama’s analysis is that even the tactical success is turning to ashes. The director-general of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) recently charged the Al Assad government with cheating on a massive scale, as reported by Foreign Policy’s Colum Lynch and David Kenner.

The “majority of 122 samples taken at multiple locations indicate potentially undeclared chemical weapons-related activities,” the OPCW found. Moreover, Syria’s attempts to explain the situation were “not scientifically or technically plausible,” according to the organisation.

The samples revealed, among other things, precursors for the nerve agents VX and soman.

Tardy compliance

This should not be a surprise. Horrific chemical weapons attacks on Syrian civilians are ongoing. Syria’s compliance with the agreement has long been understood to be grudging, tardy, and incomplete.

In sacrificing his strategic objective for a tactical gain, the president chose to trade his queen for a knight and, in the end, he lost even that. The blows to American credibility and norms against chemical weapons were devastating.

This defeat can, however, be reversed. It will take focused, determined, and vigorous diplomacy to hold the Al Assad government accountable, including through international tribunals. It will also require the administration to recognise, at least internally, that the Syria chemical weapons deal was not a proud moment.

The upcoming United Nations General Assembly meeting affords Obama an opportunity to pursue the matter personally with other heads of state.

To succeed, he will need to craft a consensus, albeit not necessarily a unanimous one, that the Al Assad government must go because it has repeatedly and grossly violated norms of civilised behaviour, and that those who ordered and conducted the attacks must be held personally responsible.

Such an ambitious agenda is rarely pursued by an administration in the twilight of its term, but it would be the right thing to do.

— Washington Post

William Tobey is a senior fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs and was most recently deputy administrator for defence nuclear nonproliferation at the National Nuclear Security Administration.