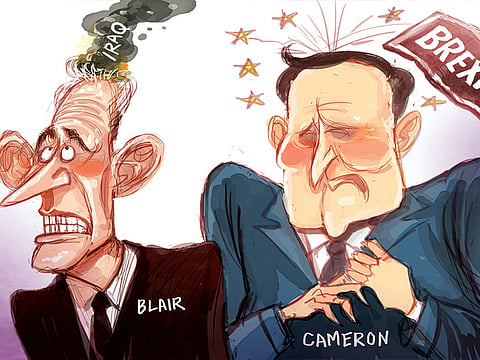

Cameron the true heir to Blair: Both were totally reckless

Trusting too much in their powers of persuasion, both men misunderstood Britain’s place in the world — and unleashed havoc

So painful was the loss of the city across the Channel, Mary Tudor predicted that anyone gazing upon her heart after her death would find engraved there a single word: Calais. When the day comes, we surely know what word will be etched into the heart of Tony Blair. It will be Iraq. And for David Cameron: Europe.

For both of these prime ministers — and, remember, one liked to see himself as the heir to the other — a single decision brought catastrophe.

The word is not metaphorical in Blair’s case. As last week’s Chilcot report laid bare, at least 150,000 Iraqis — “and probably many more” — lost their lives following the 2003 invasion, and more than a million lost their homes, displaced and dispossessed.

For Cameron, the havoc unleashed by the Brexit result is so far of the non-lethal variety. Still, the reports of hate crimes keep coming: 3,000 such incidents in England and Wales in the last two weeks of June — an increase of 43 per cent on 2015, according to the police.

History will define both Cameron and Blair by these choices, although Cameron will have less than Blair to put on the positive side of the ledger.

He could mention equal marriage, as he did in his June 24 resignation speech, along with a gracious apology for Bloody Sunday. But set against a decision that has already seen the pound become the world’s worst performing currency in 2016 and whose economic damage will be felt for years if not decades? A decision that is likely to trigger a Scottish vote for independence and the break-up of the United Kingdom? They might not count for much.

Blair will have much more to enter in the credit column. Peace in Northern Ireland, devolution for Scotland and Wales, the Human Rights Act, a minimum wage, a decade of decent funding for the NHS — it could have been quite a legacy. But it was all outweighed, even erased, in the public mind by the disaster of war in Iraq.

The result is that these two men, the dominant political figures of the past two decades, are fated to be judged harshly by posterity. Oddly, their immediate predecessors — both derided as dull, charisma-free zones in comparison — will fare better.

John Major quietly laid the ground for Northern Irish peace and presided over several years of growth. Gordon Brown kept Britain out of the euro and prevented the post-crash recession from turning into a second great depression. Above all, neither Major nor Brown started a needless war or wrecked Britain’s national prospects — thereby clearing the low bar now set by their respective successors.

The manner of these two fateful decisions was different, of course. Cameron’s mistake was to listen too much to his backbench rebels. It was pressure from his noisy, Euro-sceptic wing that pushed him into making his 2013 promise of an in/out referendum. He was spooked by the idea that Ukip could cost the Tories seats in 2015. But Ukip had no MPs at the time. Zero. He didn’t need to buckle the way he did.

Blair’s mistake was in the other direction. He did not listen to the Labour rebels — 139 of them — who voted against military action in March 2003 and who had been agitating against war for months. If he had, he could have averted calamity.

But it’s the common elements of the two decisions that are more intriguing. Chilcot saved some of his most stringent criticism for Blair’s plans for the aftermath of the invasion. They were, he said, “wholly inadequate”.

Insufficient contingency planning

Cameron is under fire now for his failure to ensure that Whitehall did sufficient contingency planning for Brexit. In the latter case, what was missing was not simply a Treasury to-do list in the event of a leave vote.

Cameron’s greater failure was that he did not think through the implications of his actions. He failed to realise what he was risking by holding this vote in this way at this time.

The Scotland factor alone should have stayed his hand. And, much as Chilcot said of Blair, these dangers did not require hindsight. They were foreseeable and foreseen at the time.

Both Blair and Cameron believed too much in their own persuasive gifts. As the “I will be with you, whatever” memo conveys, Blair thought he could win over George W. Bush to his way of thinking, whether that be taking the UN route or making a serious effort at Israeli-Palestinian peace.

Cameron similarly overestimated his powers of persuasion, believing when he promised a referendum that he would seduce his fellow European leaders into giving him what he wanted in his much vaunted renegotiation of Britain’s EU membership. Like Blair before him, he was destined to be disappointed.

Within that shared mistake was a smaller but significant one. Both Blair and Cameron were convinced that what mattered most was the man or woman at the top. Blair invested all his energy in Bush, failing to understand that power in the US system extends beyond the Oval Office. He paid insufficient heed to the alternative power centres, to the likes of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, who outmanoeuvred and outgunned him.

Cameron similarly reckoned that the only person who mattered was Angela Merkel. He thought that if only he could work his charm on her, she would give him what he needed to sell a renegotiated EU membership to a sullen British electorate. He was forgetting that in the EU there is not one “decider”. There are 27 member states to be won over. To get the kind of deal he wanted, Cameron should have acted like his European counterparts, nurturing relationships over many years. Instead he left himself weeks.

In both cases such ignorance proved calamitous. I’ve long believed that the key to understanding Blair’s motive in Iraq was his conception of New Labour: in short, whatever old Labour had done, New Labour would do the opposite. So, as Steve Richards argued in the Guardian last week, because old Labour had been estranged from the US, and Republican presidents in particular, New Labour would stand with them, shoulder to shoulder.

But that broad strategy betrayed a woeful naivety about American politics. Blair simply did not understand the nature of the Republican devil with whom he had chosen to sup. Those of us who had seen the Republican party up close in Washington in that period knew that it bristled with dangerous ideologues, best approached from a distance. But Blair was determined to be as close to Bush as he had to Bill Clinton. He refused to see the difference.

Lopsided vision

That spoke to a larger myopia Blair and Cameron shared. Both men had a lopsided vision of Britain’s place in the world, one that placed too much weight on the relationship with the US and too little on the relationship with continental Europe. Blair was ready to ignore the objections of Paris and Berlin, who opposed the invasion, just so he could stand with Washington. As Blair repeated last week, his prime objective was always to be America’s number one ally.

Meanwhile, Cameron was prepared to jeopardise Britain’s place in Europe just to get himself out of a hole dug by Ukip leader Nigel Farage and MP Bill Cash. The act of calling such a referendum, before he’d gained the concessions that might have won it, revealed that he regarded the European relationship as essentially dispensable.

David Cameron once revelled in the title “heir to Blair”. He might rethink that now, as he reflects on how much they had in common — two men who will each be remembered for a single decision of utter recklessness, one that history will be slow to forgive.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Jonathan Freedland is a weekly columnist and writer for the Guardian. He has also published eight books, including six best-selling thrillers, the latest being The 3rd Woman.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox