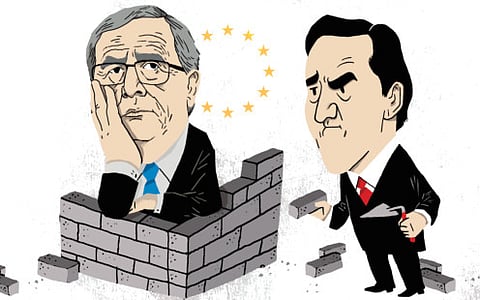

Cameron faces the great European conundrum

Even some of Cameron’s critics agree that Juncker will be a dreadful choice

‘Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die, We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.’

In 1915, during the second battle of Ypres, the Canadian physician and soldier John McCrae wrote a remarkable poem on the battlefield that caused a sensation when it was published later that year. Although he died of pneumonia in 1918, before the end of the First World War, the author of In Flanders Fields is immortalised as the man who made the poppy such a poignant symbol of shared sacrifice and remembrance across the British Empire and then the Commonwealth. This week, European leaders will gather at Ypres, close to where the poet and his comrades did battle.

Mercifully, countries that used to settle their differences by means of industrialised slaughter instead now send politicians to do deals over dinner. Europhiles point out this contrast endlessly, despite their argument being daft. They suggest that there are only two extreme choices on offer: We must have either ever closer integration leading to the creation of a European state or a return on the Continent to war and death.

British Prime Minister David Cameron is the latest leader endeavouring to convince his fellow European leaders that there must, surely, be another way. It should be possible for the countries of Europe to find a way to trade and cooperate with each other that does not involve immersion in an anti-democratic nightmare. To that end, Cameron is attempting to block Jean-Claude Juncker, the former prime minister of Luxembourg, from becoming the next president of the European Union Commission (EC). Sensibly, the Tory leader argues that as Juncker is a Eurofanatic, drunk on the idea of a country called Europe, he is not very likely to be a suitable person to reform the EU or to negotiate the recalibrated relationship that British voters want with Europe. In this effort, Cameron has a few allies in the Netherlands, Sweden and Hungary, while against him is ranged the might of Germany and most of the rest of the governments of Europe. His opponents, led by Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, argue that as Juncker was the chosen candidate of the largest grouping in the European parliament at the recent elections, then the job is his by right. That is more Euro-bunkum. I will wager that the number of European voters who knew in May that they were voting for Juncker could meet in a Munich beer cellar and find plenty of room at the bar.

Unusually, even some of Cameron’s pro-EU critics, who frequently accuse the prime minister of running scared from his Tory backbenchers whenever he attempts to make a stand in Europe, agree that the federalist Juncker will be a dreadful choice. In its latest edition, the Economist describes in great detail the various obstacles lying in Cameron’s way as he tries to block Juncker, before, in the penultimate sentence, concluding that the Tory leader is “on this issue, as it happens, right”.

There in a nutshell is an explanation of why the EU is so infuriating. Any set-up in which being right is purely incidental or an inconvenient detail that must be put to one side before the real business is done, is operating in the moral and ethical half-light. Still, it looks as though without a German retreat, Cameron will lose this crucial battle, even if Juncker’s appointment is delayed and not definitively settled at Ypres. If the Tory leader is defeated, what then? The reaction from Ukippers and the other withdrawal-ists is not hard to predict. Nigel Farage is already claiming that the appointment of Juncker will fatally weaken the Conservative leader’s promise of a EU renegotiation.

On the Tory benches, too, there is disquiet, and in the aftermath, some of the usual suspects are bound to find it impossible to resist the calls from broadcasters asking them to share their thoughts on Cameron’s defeat with an uninterested nation. But the prime minister should get considerable credit for trying, because on the question of the EU, there is not a simple answer. That is not how it looks from the Ukip perspective, of course, where it is just a matter of getting out tomorrow.

However, from where most British voters sit, the European situation looks much less straightforward. A YouGov poll last week suggested that for now, voters are up for staying in by 44 per cent to 36 per cent, and they would vote 57 to 22 to stay in the event of a successful renegotiation. They seem to want continued trade and some form of deal — the very option that will be taken off the table with the appointment of Juncker.

For moderate Eurosceptics it is tempting, but wrong, to think that this infernal impasse could be resolved with a simple swing of Margaret Thatcher’s handbag and the incantation of some old slogans. In her honour, the Centre for Policy Studies held a brilliant conference last week at the Guildhall in London, where an extraordinary array of conservative speakers came to discuss the future and the legacy of Thatcherism. The theme was “liberty”, but what nagged at me was that there was a flaw at the heart of the Thatcherite analysis, which she had identified herself late in her premiership, after she had signed so much away in pursuit of creating a single European market. Her awakening sprung from a realisation that she had helped unleash forces that threaten the nation state. She was for globalisation — and the unlimited flows of capital, goods and services — but would she today have been for global open borders and the ultra-liberal free movement of people that have come with it?

Certainly, Thatcher was a free-trader, but she was also interested in the integrity of the nation state and the maintenance of robust national institutions, which are undermined by globalisation. In this way, the manner in which the EU has split and discombobulated the Tory tribe, ever since her conversion to the cause of Euroscepticism, should be seen not as the manifestation of some perverse psychological craving for dysfunction and dispute. Rather it is the result of a genuine attempt to grapple with the greatest democratic question of our age. In an era of globalisation, replete with big trading blocks, huge cross-border corporations, mobile populations and the growing power of the big “tech” firms, what, if anything, is the role of the conventional democratic nation state?

In Europe, in a quiet way, Cameron is trying to broker a compromise that may preserve the EU as a collection of distinct states. If his fellow leaders do not listen, and Juncker is appointed, other European countries should not be surprised if many Britons conclude in a few years’ time that there really is no alternative to leaving.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2014