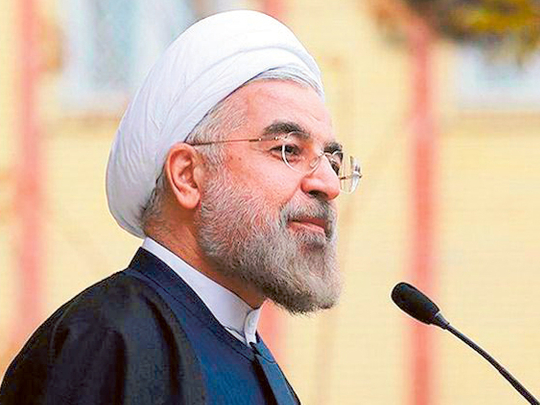

In his January 4 speech to 1,500 economists, Hassan Rouhani appeared to be fiercely critical of his hardline opponents. During his remarks, he warned that “in some cases,” the domestic political currents opposing his policies are “very powerful, very powerful, more than you think.”

Rouhani, unlike his like-minded predecessor, Mohammad Khatami, does not shy away from pulling to Iran’s domestic political stage the factional infighting between his camp, the moderates, and the hardliners’/conservatives’.

As it stands now, Rouhani is in conflict with the hardliners on four fronts.

First, he seeks to eliminate their grip over the economy, which has been widened during, and as a result of, sanctions. To that end, Rouhani is pushing for changes on several fronts: Taxing companies and operations under their control that until recently were not paying taxes, liberalising the economy, encouraging transparency, and promoting the “elimination of monopolies.”

“Our economy will not prosper as long as it is monopolised,” Rouhani said. In the same January 4 speech, he added, “We are trying to tax everyone across the board, but as soon as we touch this or that institution, they make such a stink about it.”

Rouhani’s second point of confrontation with conservatives concerns the debate regarding republicanism. The moderates, ideologically led by the former Iranian president, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, maintain that republicanism and Islam are two inseparable pillars of the Islamic Republic. They emphasise peoples’ participation in governance and view society, as Rafsanjani contends, as “the most reliable base” that ensures the survival of the system.

The conservatives, however, de-emphasise republicanism. They argue that nezam (Iran’s political system) is legitimised by religion, while its acceptance comes from the support of the people.

Undoubtedly, moderates view the advocacy of this populist idea also as a political strategy to strengthen their position against their rivals. This viewpoint, popular especially among the middle and upper-middle class urbanites, opens the third contentious front between the two sides over paternalistic policies.

In a May 2013 conference in Tehran, followed by a war of words between the two sides, Rouhani said, “We can’t take people to heaven by force and with a whip. … Let them choose their own path to heaven.”

Ayatollah Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi, ultra-conservatism’s flag-bearer, responded, saying, “Where did you get your religion from, Feyziyyeh (the seminary school in the holy city of Qom) or England?” pointing to Rouhani’s PhD, obtained from the United Kingdom.

Fourth, Rouhani and the hardliners are antagonistic with each other over Iran-US relations. This issue has been debated since the founding of the Islamic Republic of Iran by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. In the last years of his life, according to Rafsanjani, he wrote a letter to Ayatollah Khomeini, saying, “The style that we have adopted now, not to talk or have any relations with America, is not sustainable.”

In a similar vein, Rouhani, during his election campaign, remarked, “We should have started the policy of defusing tension with the US 10 years ago. Now, we are in the stage of hostilities. … We must first diminish the hostilities back to tension and then try to defuse it.”

Moderates view hostility with the US as a determining factor in Iran’s international isolation. This is important to them because they have a worldlier worldview and are significantly more economy-oriented than their rivals, who put ideology before worldly life. “Our ideals are not bound to centrifuges but to our heart and determination,” Rouhani said in his January 4 speech.

He continued: “Until when should our economy subsidise our policies? It subsidises both our foreign and domestic policies. … Let’s have our foreign policy subsidise our economy, and let’s see what happens to the people, their livelihood and the employment of our youth.”

It is in this context that, by aiming to bring Iran’s isolation to an end, moderates seek an American detente. “By God, by Lord, it is impossible: the country cannot have sustained [economic] growth when isolated,” said Rouhani.

Conservatives, however, worry that the potential outcome of restored Iran-US relations includes reshaping Iranian society. Such reshaping could facilitate the rise of technocrats through trade and commercial exchanges and lead to a tourist explosion, given the large population of Iranian expats in the US. Technocrats, who by nature hold western rather than Islamic values, may ultimately challenge the Iranian Islamic system’s authority and demand a fair share of power.

Meanwhile, in this respect, Ayatollah Khamenei’s viewpoint is in contrast with Rouhani’s. He believes Iran should rely on its domestic capabilities and not the removal of the sanctions. “Efforts must be made to immunise Iran against the sanctions” he said in his January 7 speech. Attacking the US and referring to it as enemy, he argued that the US cannot be trusted to lift sanctions in a future nuclear deal and instead called for what he has theorised as “economy of resistance.”

The highlight of Rouhani’s speech was the unexpected nudge toward a constitutional referendum regarding “crucial, disputed matters” between the two groups. “On a crucial matter that affects all of us and our livelihoods, let’s ask people’s opinion directly, just for once,” he said, without clarifying the subject of the proposed referendum.

His statement sparked speculations as to what he was referring to.

Rouhani has repeatedly made domestic promises to save Iran’s economy, which was spiralling downwards as a result of sanctions and mismanagement under former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. With oil prices dipping more than 50 per cent in the last six months, Rouhani’s only hope is to strike a nuclear deal with the P5+1. This move would give Iran access to its estimated $100 billion (Dh367 billion) in blocked assets and enable it to sidestep US sanctions by unfreezing its new oil revenues which will be tied up in international banking system if the talks fail. In addition, a nuclear deal would substantially decrease economic uncertainty, thus significantly promoting domestic and international investments in Iran.

Rouhani knows that any nuclear deal, regardless of its validity, will be met with swift hardline opposition. The majlis (parliament) would lead the charge, as it is dominated by conservatives and must approve any international “treaties, protocols, contracts, and agreements.” On the other hand, according to the Iranian constitution, holding a legislative referendum also requires the approval of two-thirds of parliamentary members.

Given the current political climate, Rouhani’s referendum strategy may proceed in the following manner: If majlis rejects the final nuclear deal, Rouhani could justify his failure of fixing Iran’s economy by placing blame on hardline members who voted against the deal. And, no doubt, he will. That will most likely drastically affect their chances for re-election in March 2016’s parliamentary elections in favour of moderates. Thus, conservative members’ best option could be voting for the referendum and hoping for nationwide disapproval. After all, they dominate control of state media, including TV and radio stations and are ‘very powerful’.

Iran’s supreme leader, however, implicitly showed his discontent with Rouhani’s January 4 statements. On January 7, he urged the nation to help Rouhani’s administration but warned that administration officials should “avoid creating a brawl and, while restraining from unnecessary statements, should not drive a wedge [in the system].”

Shahir ShahidSaless is a political analyst writing primarily about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs. He is also the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace, published in May 2014.