A few months before he died in May 1964, India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru gave an interview to the English travel writer Eric Newby, who had embarked on a foolish scheme to sail a raft down the world’s most sacred river. Newby tells the story of their encounter in his book, Slowly Down the Ganges. “This was the one [interview] at which our friend, the cockney photographer Donald McCullin, had made his immortal remark to the prime minister: ‘Mr Nehru,’ he said, bobbing up from behind a sofa from the shelter of which he had been photographing the great man. ‘You must find it difficult to control this rough old lot.’ The prime minister had not taken kindly to this remark.”

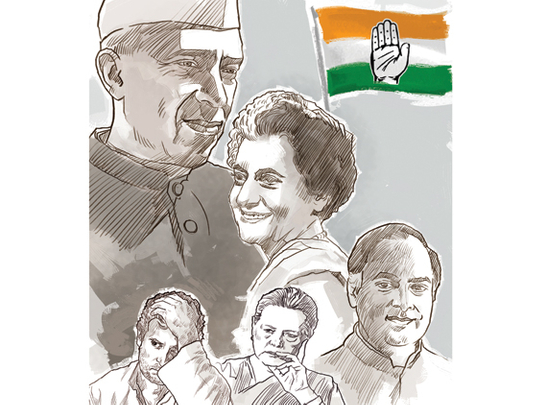

Well, of course he had not. It was an insult on several levels: To the 450 million people who then lived in India, to their heritage and traditions, to the world’s largest democracy of which Nehru had been the chief architect, to a popular leader to whom the idea of “control” was offensive. On the other hand, perhaps McCullin divined something about Nehru that has remained true of all his descendants: That he was not quite like the people he led and not just because he lived more comfortably than the great majority of them or had a better education or a successful politician’s gifts and tricks of personality. He was separate in some more fundamental way. A kind of Englishness obviously had something to do with it. A youthful progression through Harrow, Trinity College Cambridge and the Inner Temple made him more English, as the word used to be understood abroad, than a cockney photographer who left his Finsbury Park secondary modern at 15. But there was also an elevation that came from his looks and his bearing; in the iconography of Indian independence, Mahatma Gandhi was the saint and Nehru the prince.

These qualities and the isolating effects of fame left him a lonely figure, the more so because his wife died when he was in his 40s (and she in her 30s), ending a marriage that had never been close or happy. Nehru, thereafter, found physical and intellectual intimacy in friendships with non-Indians such as Edwina Mountbatten and Clare Boothe Luce, or Indians who had lived almost entirely abroad, such as Krishna Menon. The life of his daughter, Indira, followed a similar pattern — an unhappy marriage to Feroze Gandhi that ended in separation and then her husband’s death aged 47, with her most confessional friendships kept mainly with people who lived thousands of miles away.

Father and daughter were busy private correspondents, given that they were also Indian prime ministers. At the start of his passionate relationship with Edwina, Nehru wrote to her every day and went on writing weekly or fortnightly until the day she died. The contents of his letters remain unknown, or at least unpublished, but one of her replies suggests the deepest intimacy: “I think I am not interested in sex as sex. There must be so much more to it, beauty of spirit and form. But I think you and I are in the minority!” Indira’s letters to her friend Dorothy Norman, a New York writer and editor, also yearned for things she could not find at home. “The desire to be out of India and the malice, jealousies and envy, with which one is surrounded, are [sic] now overwhelming,” she wrote just before her father died. “Also the fact that there isn’t one single person to whom one can talk or ask advice even on the lesser matters.” And yet less than two years later she was prime minister.

‘Spectacle’ of religion

The Nehru-Gandhi family was firmly established as a political dynasty by the 1980s. When Rajiv, Indira’s son, lost his last election in 1989, three generations had ruled India for all but four years of its independent history. Rajiv’s assassination in 1991 brought only a pause in the family’s influence inside the Congress party, which by now was little more than the vehicle for the Nehru-Gandhi brand. Rajiv’s widow, Sonia, became the party president and the woman to whom the last Congress prime minister, Manmohan Singh, deferred. Rahul Gandhi, her son, was groomed as his successor. If all had gone well for him, his family’s position as India’s ruling dynasty would have stretched across four generations.

Still, they have never seemed as though they utterly belonged to the place. They have shown an exemplary disregard for social taboos by marrying into other communities and countries. Indira, the daughter of Kashmiri Brahmins, married a Mumbai Parsi. Rajiv married the daughter of a building contractor from a small town near Turin, Italy.

Nehru’s great-grandson, Rahul, is therefore a quarter Kashmiri, a quarter Parsi and half Italian — a fine emblem of social liberalism and national integration, though that may please his grandfather rather more than his constituents in rural north India. Likewise with religion: Long before Alastair Campbell, the Nehru-Gandhis did not do God. “The spectacle of what is called religion in India and elsewhere has filled me with horror,” Nehru wrote, “and I have frequently condemned it and wished to make a clean sweep of it.” His grandson Rajiv was only slightly less pliable when I interviewed him in 1985. No, he never prayed to God. No, he had never believed in God. He conceded that his mother had gone a little off the rails towards the end of her life by taking up with swamis and yogis and consulting astrologers (she had premonitions, correctly, of a violent death), but she had brought him up to be agnostic and “secular”, a word that in India has to bear too much hope.

Like his grandfather before him, and his son after him, Rajiv went to Trinity College Cambridge (where unlike them but like his mother at Oxford, he failed to get a degree). Oxbridge and the Ivy League universities remain the educations of choice for the Indian elite, but the political class now reflects a much more Indian reality.

However much the socialist idealism of Nehru may have wished it, it seems unlikely that he could ever have imagined that his latest successor would have started his working life as a tea boy at a wayside railway station, or that his own great-grandson would prove such a political dud and quite possibly the terminus of the Nehru line.

Less deference and more aspiration on the part of the electorate can explain most of this outcome. The more difficult question is why Sonia ever wanted her son to be prime minister, and why Rahul allowed himself to want it? Doing the same job, his grandmother had been mowed down by automatic gunfire and his father blown to pieces by a suicide bomber in separate incidents with separate causes, seven years apart. According to reports, all that was left of his father were his head and his feet, which were wearing a pair of running shoes. Rahul was 20 at the time.

To overcome the reasonable fear that the same could happen to you requires an odd belief in, what? Destiny, duty, power? Especially when nothing other than a name suggests you would be any good at politics. But perhaps mother and son and their party are locked in a dance that none can escape.

This week, they offered to resign as Congress’s president and vice-president and the party refused their resignation. The last bit of England in Indian politics looks set to die a slow death.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd