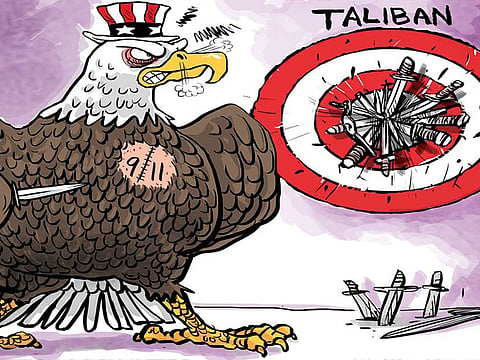

America’s war without an end

The US needs to answer some painful questions as its military operation in Afghanistan drags on, 15 years since it started

On October 7, 2001, American and British forces began air strikes in Afghanistan after the Taliban refused to hand over Osama Bin Laden, blamed for the 9/11 attacks. This was followed by an invasion of the country by the United States, supported by troops from Nato and other allies, under Operation Enduring Freedom. Though in May, 2011, American Navy SEALs helicoptered into Pakistan and finally killed the Al Qaida leader, the war in Afghanistan drags on, becoming the longest in American history.

A coalition from the so-called developed world, spearheaded by the leader of the free world, that waged war against a nation from the developing world, but was unable to finish what it had started 15 years ago, has a lot of explaining to do.

Last week, Taliban fighters, who effectively control one third of Afghanistan, penetrated Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province. Though they had not raised their flag over the strategic southern city and were later pushed back, the psychological damage was done. Ironically, the Taliban ground assault came two days after General John W. Nicholson, the US and Nato military commander in Afghanistan, flew from Kabul to Lashkar Gah and promised worried local leaders that his forces would make sure the city would not collapse. Abdullah Habibi, the Afghan Defence Minister, who accompanied Nicholson, promised the group that his forces would “defend Lashkar Gah with our blood”.

Maybe. Maybe not. Later in the week, Taliban members disguised as police officers, brazenly attacked a Shiite shrine packed with hundreds of worshipers in the heart of Kabul. And so it goes.

Fifteen years and counting.

Fifteen years and counting more than $850 billion (Dh3.12 trillion) of taxpayer money spent by the US, of which, $110 billion has gone towards “reconstruction”, even as 2,300 Americans and well over 91,000 Afghans were killed in a war against a group of insurgents that had shown no hostile ambitions against the West.

Yet, America remains there, 15 years on, engaged in bloody conflict in the most violent corner of one of the world’s most violent nations.

Why? Does America, as a superpower, like other superpowers before it in history, have a reservoir of unused turbulent energy that it needs to sublimate by launching wars? Much in the manner the Europeans had done when they launched the first war of the 20th century, thereby putting an end to that era between the 1870s and the 1910s — between, say, Waterloo and the Somme — an era characterised by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity and literary innovation. It was an era that was outwardly serene, but menacingly ripe beneath the surface with anarchic compulsions.

To follow on Sigmund Freud’s poetic essay, Civilization and Its Discontents, does a superpower, by virtue of it being a superpower, bring with it the need to unleash the terrors of history on the world, terrors that spawn in the individual, as in the collective consciousness, a death wish? Do Americans need, just need, to go to war against a perceived enemy, any perceived enemy, whether they find him or her in the Philippines, in Vietnam, in Afghanistan, in Iraq or elsewhere?

Do people from such a polity need constantly to combat the tensions that civilised manners — today we call these political correctness — impose on unfulfilled human instincts? And do citizens, socialised in a superpower — as Frenchmen, Germans, Englishmen and other Europeans had felt during their heydays, on the eve of the two devastating World Wars — feel an inescapable drive towards a supremacist assertion of identity?

These are questions that, along with Freud, cultural critics, all the way from T.S. Eliot in Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1948) to George Steiner in In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1971) have considered cardinal to any contemporary theory of what we call culture.

Fifteen years ago, Americans went to fight a war in a country known as one of the world’s poorest, a country resistant to change, scornful of outsiders who wanted to win over its people’s “hearts and minds” by force of arms rather than by force of friendship.

So what is to be done now? Let Washington take its cue from the late Senator George D. Aiken of Vermont who, in 1966, at the height of yet another costly war that the US was waging against “peasants in black pajamas” in Vietnam, called on the White House to simply “declare victory and get out”.

Come to think of it, that’s precisely what the New York Times, resorting to less folksy language, appears to advocate these days. “The Afghan government remains weak, corrupt and roiled by internal rivalries”, an editorial in the Grey Lady, a publication whose influence at times surpasses that of the White House, said on September 17. “The casualty rate for Afghan troops is unsustainable. The economy is in a shambles. Resurgent Taliban forces are gaining ground in rural areas ...”

In short, the US needs to answer some painful questions. “One such question”, the editorial added, “is whether the Afghan Taliban — an insurgency that has never had aspirations to operate outside the region — is an enemy Washington should continue to fight. American forces started battling the Taliban in 2001 because the group provided safe haven to Al Qaida, which was based there when it planned the September 11, 2001, attacks on America. While Al Qaida has largely been defeated, the Taliban has proved to be extraordinarily resilient”.

Great advice. Fellows, declare victory and get the devil out.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.