A series of Taliban assassinations has spread panic in Afghanistan's ruling elite, increasing ethnic tensions and jeopardising the imminent transition from US and Nato forces to Afghan forces. As the military situation deteriorates, the dialogue process with the Taliban must be sped up. But for this to happen America must also suspend its own lethal night raids against Taliban targets.

Since March, seven top Afghans have been assassinated, including three in the critical southern province of Kandahar. They included Ahmad Wali Karzai, President Hamid Karzai's brother, and Gulam Haider Hamidi, the mayor of Kandahar, considered to be one of the most honest officials in Afghanistan — who were both killed in July.

Many senior officials have reacted to this new unrest by sending their families abroad, or stopping them from leaving their heavily-guarded homes. Governance outside Kabul is at an all-time low, as officials bunker down in their offices. At the same time Karzai faces a parliamentary crisis, with the opposition threatening impeachment and a cabinet that has still not been completed after six months of delays. The state faces financial problems too. The International Monetary Fund, along with other agencies and donors, has sent no payments or loans to the central bank for four months, due to corruption scandals at the Kabul Bank that Karzai has failed to address.

The US and the Afghan government are at loggerheads over what kind of residual US forces will stay behind, when the bulk has left in 2014. There is also the question of whether the two sides will agree to a new security framework agreement. The Afghans want more money and arms post-2014 than the Americans are currently prepared to commit.

As a result, Afghans are more doubtful than ever that the West can safely hand over to Afghan forces who can protect its population. This, in turn, creates a difficult backdrop for the early stages of peace discussions with the Taliban. Here there are growing criticisms of the secret talks from important Afghan minority groups, raising fears that an eventual power-sharing deal may not be accepted, leading to serious ethnic differences or a new civil war.

This is where the night raids matter. The Pentagon, which has been at odds with US President Barack Obama over the troop withdrawal, is not fully supportive of the current round of talks. It also considers night raids, carried out by special forces such as the elite Navy Seals, to be one of its major weapons to degrade the Taliban.

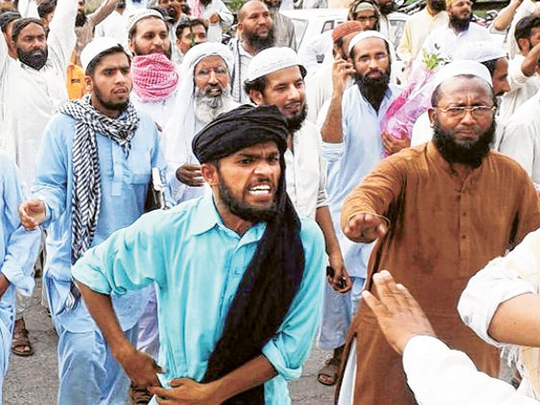

Yet while the raids have killed numerous commanders, they also generate enormous fear among the wider population. There are strident demands by Karzai to stop them. The Pentagon is not listening.

Since the death of Osama Bin Laden, American officials have tried to divert attention from problems on the ground by hyping up the possibility that Al Qaida is on the ropes. They argue that the deaths of just 20 more leading figures — perhaps also in night raids — could see the demise of the organisation in Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, even that justification is exaggerated. Al Qaida's high command in south Asia now includes a greater number of Pakistanis and central Asians, who train recruits and plan attacks. Bin Laden's killing was a blow, but it has certainly not caused the end of the organisation.

Confidence-building steps

But public anger at night raids remains one of the main justifications for the current Taliban offensive, in addition to being a form of retaliation for previous US raids. If the offensive continues, there is a risk that further assassinations could lead to a complete collapse of leadership in the frail Afghan government bureaucracy and police.

Given this precarious situation, it is becoming more urgent for the US and Nato to speed up talks with Taliban leaders. Faster negotiations, however, require confidence-building measures. These should include a promise from the US to halt night raids in exchange for an end to the assassination campaign of Afghan officials. Further measures could then aim gradually to lower the level of violence, making it easier to carry out the transition.

The Taliban say they are not going to hamper a US withdrawal from selected areas, as long as the Americans do not target them. Meanwhile, aides close to Karzai say it is America's finger that is on the trigger, and there is little they can do beyond asking for an end to night raids. The onus for stability rests on the Americans but if they continue down the present path, the transition to Afghan forces could quickly turn into a debacle.

— Financial Times

Ahmed Rashid is author of Descent into Chaos: How the War Against Islamic Extremism is Being Lost in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia.