Age of accountability is upon us

The International Criminal Court casts an increasingly long shadow. Those who would commit crimes against humanity have come to fear it

Twelve years ago, world leaders gathered in Rome to establish the International Criminal Court (ICC). Seldom since the founding of the United Nations itself has such a resounding blow been struck for peace, justice and human rights.

On Monday, nations come together once again, this time in Kampala, Uganda, for the first formal review of the Rome treaty. It is a chance not only to take stock of our progress but to build for the future. More, it is an occasion to strengthen our collective determination that crimes against humanity cannot go unpunished — the better to deter them in the future.

Great progress

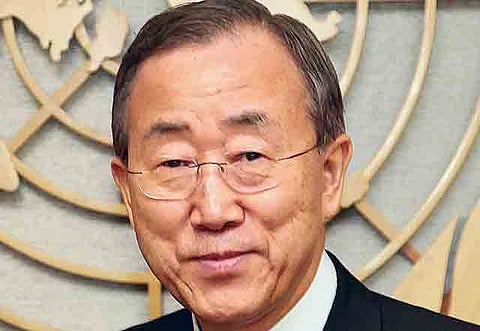

As UN secretary-general, I have come to see how effective the ICC can be — and how far we have come. A decade ago, few could have believed the court would now be fully operational, investigating and trying perpetrators of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity across a broadening geography of countries.

This is a fundamental break with history. The old era of impunity is over. In its place, slowly but surely, we are witnessing the birth of a new "age of accountability". It began with the special tribunals set up in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia; today, the ICC is the keystone of a growing system of global justice that includes international tribunals, mixed international-national courts and domestic prosecutions.

So far, the ICC has opened five investigations. Two trials are underway; a third is scheduled to begin in July. Four detainees are in custody. Those who thought the court would be little more than a "paper tiger" have been proved wrong. To the contrary, the ICC casts an increasingly long shadow. Those who would commit crimes against humanity have clearly come to fear it.

And yet, the ICC remains a court of last resort, stepping in only when national courts do not (or cannot) act. In March, Bangladesh became the 111th party to the Rome Statute, while 37 others have signed but not yet ratified it. Some of the world's largest and most powerful countries, however, have not joined.

If the ICC is to have the reach it should possess, if it is to become an effective deterrent as well as an avenue of justice, it must have universal support. As secretary-general, I call on all nations to join. Those that already have done so must cooperate fully with the court. That includes backing it publicly, as well as faithfully executing its orders.

The ICC does not have its own police force. It cannot make arrests. Suspects in three of the court's five proceedings remain free, living in impunity. Not only the ICC but the whole of the international justice system suffers from such disregard, while those who would abuse human rights are emboldened.

The review conference in Kampala will look for ways to strengthen the court. Among them: a proposal to broaden its scope to include "crimes of aggression", as well as measures to build the willingness and capacity of national courts to investigate and prosecute war crimes.

Striking a balance

Perhaps the most contentious debate will focus on the balance between peace and justice. Frankly, I see no choice between them. In today's conflicts, civilians are too often the chief victims. Women, children and the elderly are at the mercy of armies or militias who rape, maim, kill and devastate towns, villages, crops, cattle and water sources — all as a strategy of war. The more shocking the crime, the more effective it is as a weapon.

Any victim would understandably yearn to stop such horrors, even at the cost of granting immunity to those who have wronged them. But this is a truce at gunpoint, without dignity, justice or hope for a better future. The time has passed when we might talk of peace versus justice. There cannot be one without the other.

Our challenge is to pursue them both, hand in hand. In this, the ICC is key. In Kampala, I will do my best to help advance the fight against impunity and usher in the new age of accountability. Crimes against humanity are just that — crimes against us all. We must never forget.