The death of former president of Iran, Hashemi Rafsanjani, a few days ago, once again highlighted the many contradictions that defined the Iranian Revolution that almost always pretended to be something it was not.

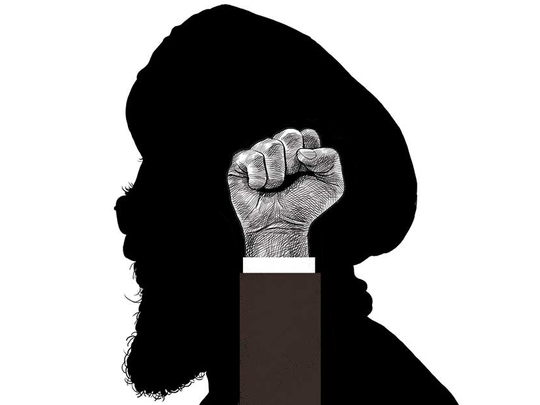

Rafsanjani was one of the founding leaders of the 1979 revolution that overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy, removed limited liberal norms, sought to establish strict religious canons, imposed the velayat-e faqih [jurisconsult of God] as a Shiite political philosophy and otherwise promised to champion the rights of the oppressed [mustaz’afin]. It was worth recalling that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini launched his systematic criticisms of presumed oppressors [mustakbirin], and insinuated that he and his clergymen would be the paragons of transparency, which turned out not to be the case.

Four decades hence, economic inequalities flourish with Rafsanjani’s political fortune estimated to be in excess of $1 billion (Dh3.67 billion) according to a 2003 Forbes magazine assessment. Still, Rafsanjani’s alleged prosperity paled in comparison to that amassed by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who supposedly controls a private financial empire estimated at $95 billion. Even if this evaluation — advanced by the London’s Telegraph — was exaggerated on account of Khamenei’s Spartan lifestyle, there is plenty of evidence to support how the “Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam” [Setad in Farsi], expanded into a business juggernaut with stakes in every sector of the Iranian economy. A 2013 Reuters investigation revealed that Setad assets included finance, oil, telecommunications, the production of contraception pills and even ostrich farming, in its growing portfolio. Parastatal organisations with sophisticated mechanisms played vital roles, as wily clergymen carefully vetted most institutions, anxious to benefit from the system they established. The revolution, as revolutions go, turned out to be an excellent business opportunity for those in power even when elites espoused pristine and, as necessary, divine ideologies.

Remarkably, Rafsanjani, who rose from modest origins since his father was a small-scale pistachio farmer, led the way as he adopted pragmatic steps. Others emulated him, as Iran embarked on a sustained “privatisation” programme, which allowed a revival of the stock market, along with liberalised policies to encourage foreign trade and private investments in vital sectors like oil and banking.

Yet, when the infuential and their associates grabbed choice assets and secured juicy contracts, notwithstanding showcase trials for putative crooks caught with their hands in the proverbial cookie-jars, the public mobilised against the regime. One of the key reasons for the 2009 uprisings, which were violently repressed, was to end such criticisms on the pretext that Iran confronted foes and needed to stand tall. No wonder Tehran referred to the opposition Green movement as “sedition” since the threat was to the pockets of the influential.

In fact, while clerics engorged themselves on the country’s wealth, ordinary Iranians paid the price. Excessive expenditures — fuelled by wars that were and are driven by unprecedented ideological ambitions — impoverished the masses. Inflation roared. The Iranian rial, which traded around 9,200 to 1 US dollar in 2006, exchanged at 41,600 to $1 in late December 2016 — a depreciation of some 450 per cent. The trend was for more of the same.

As if this is not bad enough, concerns about the country’s inabilities to handle the onslaught of anti-Iranian declarations (which were expected to be translated into policies) made by United States President-elect Donald Trump and his appointees, are bound to further destabilise shaky markets. How such instability spilled over inside Iran is anyone’s guess, although Rafsanjani’s death is bound to empower hardliners and, correspondingly, further weaken President Hassan Rouhani in the upcoming presidential elections in mid-2017. Rouhani, who has stabilised the currency after years of volatility and helped lower inflation down to single-digit rates from above 40 per cent in 2013, is not a shoe-in and faces steady opposition. Only time will tell whether he will prevail.

For now, it is fair to ask whether Iran can manage to dissuade Trump from scrapping the deal between Iran and the P5+1 (United States, Britain, France, China, Russia plus Germany) powers that imposed strict restrictions on Tehran’s nuclear projects? Will Washington re-impose sanctions on the Iranian economy after this month, as contemplated by the Trump? How will these measures endear Iran to foreign investors whose presence is vital to help modernise the Iranian economy?

Understandably, Iranian officials posit more optimistic assessments and claim that the slide of the rial was anachronistic. Samad Karimi, head of the exports department at the central bank, blamed the fall on a temporary surge in demand for travel, while a spokesman for the government, Mohammad Baqer Nobakht, affirmed that the drop was due to “psychological issues”. Notwithstanding intrinsic abilities as spin doctors, revolutionary Iranians who dismissed various tensions, risked far more than internal and regional opposition. They risked peace and stability.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of the forthcoming The Attempt to Uproot Sunni Arab Influence: A Geo-Strategic Analysis of the Western, Israeli and Iranian Quest for Domination (Sussex: January 2017).