An American journalist once complained to me about the stories British media told about his home country. It wasn’t a question of political bias, he said, but of snobbery — a condescending cocktail of indulgence and contempt: “You talk about us like explorers documenting the customs of some primitive tribe.”

Liberal opinion in Europe was offended that the race should even be close. In Al Gore we had a dependable, heavyweight statesman-in-waiting. “Dubya” was a self-satirising cartoon of the crass, gum-chewing American dolt in a cowboy hat. Clever versus dumb. How hard could it be? But former United States president George W. Bush was not actually stupid. He could be inarticulate, mangling his script into semi-comic neologisms, but he made that weakness a strength. It camouflaged his east-coast establishment pedigree better than the affected Texan drawl. His enemies underestimated him. Bush misspoke for millions of Americans who felt that the smarter, slicker-tongued elites were laughing at them.

The emblematic moment of the race was Gore’s exasperated sigh as Bush started speaking in a televised debate. In that bored exhalation there was a halitosis of disdain for the ignoramuses whose refusal to keep up with the Enlightenment sometimes makes it hard for busy professional liberals to love democracy with all their hearts.

Britain’s pro-Europeans should study that moment carefully. If their referendum campaign is lost, the cause will sound something like Al Gore’s sigh. There can’t be an endorsement of the leavers’ post-referendum plan, since they don’t have one. There is not a clear vision of national destiny outside the European Union (EU) on which Brexiteers can agree.

The best resource they have is a natural reservoir of anti-elite resentment, filled over time by tributaries springing from different political directions. Whether the grievance is focused on immigration, regulation, parliamentary sovereignty, human rights law or vague distaste for the thing called Brussels, the common theme is expropriation. It is the feeling that control of the world around you has been carried off by people who do not live like you and who do not like the way you live. If they are not literally foreign, they are alien in the looser sense — disconnected from any place you know, and looking down on it.

Mostly the ‘remain’ campaign is trying to advance cold, rational arguments, albeit weaponised with rhetorical alarm. That feeling is hard for pro-Europeans to neutralise. They aren’t equipped to fight a culture war. Mostly, the ‘remain’ campaign is trying to advance cold, rational arguments, albeit weaponised with rhetorical alarm. They spell out practical reasons why it will be a terrible idea to surrender membership of a club that Britain’s international allies say it should be a part of, that despots, racists and terrorists want to see fail, and whose rules we would mostly end up abiding by even if we left.

That is also why moderate politicians in the rest of Europe look on our referendum with bafflement and alarm. Governments in Paris and Berlin seek reassurance from their ambassadors and political contacts in London that Britain is not about to do something crazy.

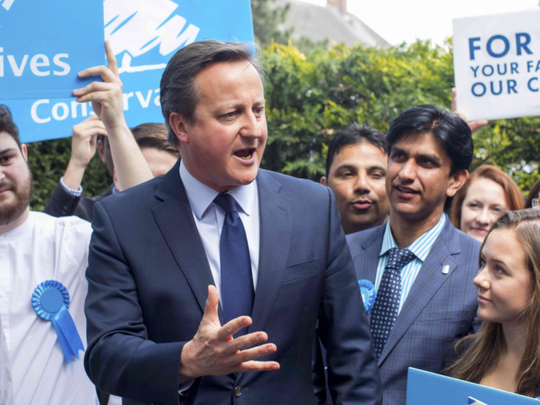

British Euroscepticism has hardly turned up unannounced in continental politics, but there was always a level of confidence in United Kingdom prime ministers to handle it. Even as fellow EU leaders watched British Prime Minister David Cameron sit at the Brussels summit table playing with United Kingdom Independence Party’s matches, they did not seriously think he might burn the place down. Britain’s flirtation with quitting the EU is starting to look to many liberal and centre-left politicians on the mainland the way ostensibly bizarre, but culturally ingrained American political eccentricities look to Britons.

One equivalent that springs to mind is the argument around gun control. To the non-American, it is blindingly obvious that arming everyone with deadly weapons leads to more deaths, and that restricting the flow of guns might reduce the number of people getting shot. Viewed from that angle, it takes quite a leap of political empathy to sympathise with veneration of the constitutional right to bare arms and to see gun control as a tool of liberal tyranny over self-sufficient, law-abiding citizens. But without that act of empathy, the debate makes no sense at all. So it is with British Euroscepticism. Idon’t mean that leave campaigners are bullet-headed maniacs.

Every country has national fables and idiosyncrasies that shape public debate in terms that seem perversely lopsided to anyone not steeped in the history that generated them. Whether pro-Europeans like it or not, the impulse to leave the EU triggers nerve endings that reach deep into the British psyche: the island geography, the trauma of post-imperial decline, the sentimental impossibility of judging any hour finer than that one in 1940, when Britain stood alone against the Evil that had overrun the continent. It isn’t yet clear whether that is enough to mobilise a majority for Brexit.

The hurdles of economic risk-aversion are very high. The reservoir of anti-elite resentment is deep, but there is no firm evidence yet that the waters are rising. The ‘leave’ campaign is not galvanised behind a single leader. It is also thrown off balance by a tension between the need to reassure cautious swing voters that it is not a vandal insurgency and the demagogic urge to set nationalist pulses racing.

The hazard for ‘remain’ supporters is not so much losing the debate as losing the audience. It is the risk that confidence in the pragmatic case for EU membership spills into impatience with voters who are swayed by other factors. It is the danger that somewhere from the parade of world leaders, former prime ministers, party grandees, heads of international organisations, experts and economists all lining up to warn Britain against a historic folly there rises a collective, Al Goresque sigh.

Already, the case for staying in the EU can come across as the tut-tutting of a liberal class that had better things to do than hold this blasted referendum, as if the uncertain voters are standing on the wrong side of the escalator of progress and need to be hurried along. It might work as a way to tip Britain over the line in favour of ‘remain’. Yet, none of the scepticism, anger or suspicion will be dispelled. That is because a referendum cannot settle a culture war, where one side can win the argument and still the other side captures the mood.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Rafael Behr is a political columnist for the Guardian. He has been the political editor of the New Statesman, chief leader writer on the Observer and a foreign correspondent for the Financial Times in Russia and eastern Europe.