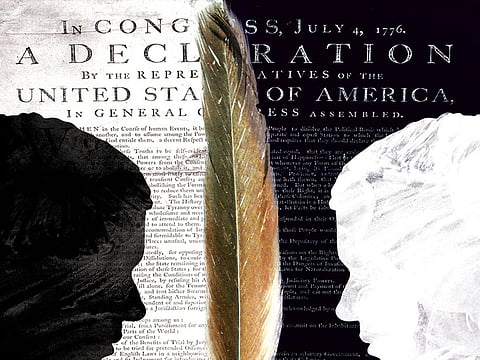

A declaration of political conflicts

For 18th-century African-American freedom seekers, freedom alone was never the whole goal; equal empowerment was and is the promised land

This Fourth of July, like the preceding weeks, was painful, following the Charleston massacre — a devastating example of the lofty ideal of human equality’s failure to take root in a human heart. Many would say, as many have said to me, that taking the ideals of the Declaration of Independence too seriously is a mistake, because the men who signed it did not. These folks say that I should be more clear-eyed about revolutionary hypocrisy. I counter that we should be more clear-eyed about how the Declaration launched two political traditions in this country: one for broad equality, and one for an equality limited to whites.

As the men of 1776 approached their fateful break from Britain, they argued over the proper orienting ideal for government: Property or happiness? On the side of happiness were John Dickinson, the only slave owner in the Continental Congress to free his slaves after the summer of 1776, and John Adams, who never owned slaves, who considered slavery wrong and whose wife, Abigail, hired free black labourers in the spring of 1776. On the side of property were the Virginians, among them Thomas Jefferson.

In the fall of 1775, Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, proclaimed that any slave who escaped and fought for the British would earn freedom. The Virginians had been slower to tip toward revolution, and Dunmore’s proclamation radicalised them. They castigated the British for an alleged violation of the “right of property” entailed by the promise of freedom to their slaves.

When the Virginians began work on their Constitution in May 1776, they compromised. George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights invoked both property and happiness.

But when it came to the Declaration of Independence itself, happiness won. This was a compromise of a different order — a suppression of the pro-slavery position. We can assume the language worked, because happiness is an open-ended term. Advocates of the pro-slavery position will have had to imagine themselves included in it. And yet the absence in the Declaration of the core term of their defence, a right to property, constituted a pregnant silence.

Abolitionists recognised this immediately. In Boston in January 1777, Prince Hall, a free African-American, submitted a petition to the Massachusetts Assembly seeking abolition in Massachusetts. Building on the language of the Declaration, he wrote: “[Negroes] have, in common with all other Men, a natural and unalienable right to that freedom, which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all Mankind.” Their enslavement, he wrote, was a “violation of the laws of nature and of nation”.

Hall was not alone. As literary historian Eric Slauter argued at a recent National Archives conference, in the years after 1776, quotation of the Declaration’s resounding celebration of rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness was generally the province of abolitionists. Indeed, the first legal moves to abolish slavery relied on the language of the Declaration. In 1777, Vermont wrote in its constitution:

“[A]ll men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent, and unalienable rights, amongst which are the enjoying and defending life and liberty: Acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety. Therefore, no male person, born in this country, or brought from over sea, ought to be holden by law, to serve any person, as a servant, slave, or apprentice, after he arrives to the age of 21 years; nor female, in like manner, after she arrives to the age of eighteen years.”

Having accepted full human equality and explicitly rejected the use of the property right to defend slavery, Vermont’s legislators could embrace property as well as happiness. Massachusetts did the same in its 1780 Constitution, which also drew on the Declaration’s language. Its constitution supported a successful 1781 suit for freedom by the aptly named Elizabeth Freeman. A few months later, Massachusetts chief justice William Cushing instructed a jury that the state constitution had outlawed slavery, an interpretation the state’s Supreme Court affirmed in 1783.

Yet, a pro-slavery states’ rights position also flowed out of the Declaration. The latter, pro-slavery tradition was incorporated into the union by means of the famous compromises in the Constitution but also through similar moves in the drafting of Declaration. Congress cut from the committee’s draft of the Declaration a condemnation of King George for protecting the slave trade.

The stark contrast between the two traditions reached its apex with the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln reached back to the Declaration in his Gettysburg Address to rededicate the country to the cause of equality. The Confederacy took the opposite stance, vigorously repudiating the Declaration. Alexander Stephens, vice-president of the Confederacy, wrote both that the original union “rested upon the assumption of the equality of the races”, and that the Confederacy “is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas: its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man”.

It is a mistake to paint the whole of the tradition of the Declaration in the colours of one interest.

To see that there is an anti-slavery tradition emanating from the Declaration as early as 1777 is not, however, the end of the matter. With his petition, Prince Hall, who fought at Bunker Hill, sought not freedom merely but political equality. Following the full logic of the Declaration’s self-evident truths, he sought his rights not only to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness but also to participate as a member of “the people” in instituting government to secure society’s safety and happiness. In 1786, he offered to supply Massachusetts’ governor with 700 men to help quash Shay’s Rebellion but was rebuffed. Two months later, he submitted a very different kind of petition to the assembly — this time seeking assistance for himself and 65 other African-Americans to leave their “very disagreeable and disadvantageous circumstances” and to return to Africa.

For 18th-century African-American freedom seekers, freedom alone was never the whole goal; equal empowerment was and is the promised land. This is the opposite of what the signs of the Confederacy stood and stand for. America has many traditions. Some should be discarded.

— Washington Post

Allen is a political theorist at Harvard University and a contributing columnist for Washington Post.