A curious historical shift

Liberty depends on ability to overcome alienation inherited from captive past

It all began ten years ago with cynicism and falsehood. US president George W. Bush dispatched his secretary of state Colin Powell to lie to the United Nations and to the world at large. Former ally Saddam Hussain possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and enjoyed close relations with the Al Qaida network established in Iraq, he claimed. Intervention could not wait. Against the counsels of the UN inspectors, including Hans Blix, and against the best advice of international institutions, the US and its allies launched a war in which hundreds of thousands were killed.

Iraqis were promised freedom. Instead, they experienced horror, devastation and death. Saddam was a dictator with blood on his hands, a monster, but — as ally or as enemy — he was used to carry out the sinister schemes of an American government totally oblivious to the consequences.

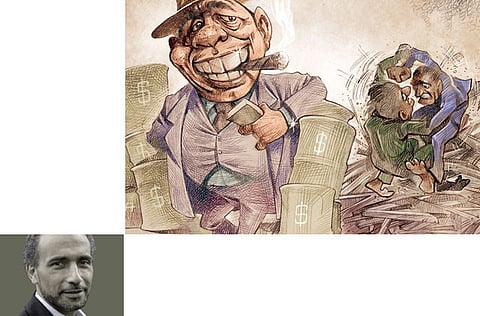

Ten years later, people continue to die; horror has become the norm. Politically, the entire operation has been a failure, a fiasco. Divisions between the country’s various religious sects and traditions have deepened, Sunni and Shiite distrust each other and kill on a daily basis. The political system, based on religious and ethnic identity, is as fragile as it is artificial. A political elite and a caste of promoters and financial operators shelter, literally and figuratively, behind the walls of the high-security zone in Baghdad. Their lives are safe, while they reap enormous profits, particularly in the Iraqi oil sector. The political and human balance sheet is a catastrophe and yet the economic and geopolitical benefits for a privileged handful have been immense.

America’s Israeli ally was one of the loudest voices calling for the elimination of Saddam, for the weakening of his “regional nuisance power,” as well as keeping the country on a short leash. From this perspective, the operation was a success. In terms of profit it was even more successful. Iraq’s oil resources have been brought under full foreign control; contracts now ensure direct access to Iraq’s oil and reconstruction projects. The American and British armies have left behind them a country torn by war and murderous violence; their corporations and businessmen have stayed on to profit from a country of enormous oil wealth and profit potential. Behind growing political instability and the illusion of democratic progress lurks increased economic domination.

In 2003, president Bush had promised to liberate Iraq before “democratising” the Middle East. The world listened and smiled: This was Bush talking, a man whose intelligence seemed inversely proportional to his capacity for lying. Still, he sometimes seemed to be describing a vision, an American strategy that had begun with Iraq and that would be later applied to other countries in the region. In reality, the aim was to secure, restore and ensure economic and geopolitical advantage by supporting, directly or indirectly, the process of democratisation in the region.

A closer look at the situation in Libya reveals striking similarities. The combined French, American, British and Qatari intervention alongside the forces of Nato brought down the tyrant Muammar Gaddafi (who had nonetheless been welcomed into the international community as a respectable partner only two years ago). The UN no-fly zone resolution was circumvented and armed intervention rapidly achieved two concordant goals: Reassert western control over the country and block Chinese and Russian access to its oil wealth. The political situation in Libya today is far from stable as violence stalks the streets, clans and tribes are at each other’s throats and true democracy seems like a pipe dream. However, Libya’s oil wealth has been brought under control, western multinationals now have a free hand and from mining to reconstruction sweetheart contracts proliferate. In both political and human terms, the country is a basket case, but economically it has emerged as a fabulous source of profits, while offering eventual access to the rich underground resources of neighbouring Mauritania, northern Mali and Niger.

Each country has its own history dynamic and hasty comparisons must be avoided. However, one would be shortsighted not to notice the shape of the emerging foreign domination of the Middle East. The struggle between the US and new international players — like the Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), not to forget Turkey — the future of region’s regimes and their democratisation counts for little. The Arab awakening was not at all an awakening of the conscience of the Great Powers to the quest for freedom and dignity of the people of the Global South. Both Tunisia and Egypt have experienced two years of painful transition. Their people rose up and brought down dictators. Two years later, the democratic process has faltered. Divisions, tensions and violence threaten achievements. Internal and external forces are working to destabilise the two countries (not to mention the questionable role of the Armed Forces in Egypt). There is every cause for alarm. Their Islamist leaders have no choice if they hope for political recognition and respectability (not to mention urgent reforms). They must accept the economic policies imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Both economies are in ruins; no political force is in a position to put forward a political alternative or call for a strategic re-orientation. Caught up in conflicts and constant political infighting, the Islamists in power in Tunisia and Egypt, as in Morocco, are forced to become docile partners of the very same powers who just yesterday supported the dictators that tried to suppress them. A curious historical shift indeed.

Ideological alignments, which remain extremely fluid, cannot explain events in the Middle East quite as well as the pragmatism of its leaders, which often is little more than another term for surrender.

Today’s Middle East is fragile, unstable. Anything can happen, as the region increasingly becomes the object of insatiable appetites. The struggle for influence, alongside the cynicism that the passivity of the Great Powers, helps to explain the daily horror taking place in Syria. Regional instability, assiduously promoted division between Sunnis and Shiites, efforts to isolate Iran, tensions in Lebanon and the partisan involvement of some oil-producing states have created a disaster and an object of pity. History teaches us that there are no limits to political cynicism. The “low intensity conflict” in Syria may be horrifying in human terms, but it may well prove to be geopolitically “profitable”.

The Middle East as a political entity is trapped in its divisions, while predators destroy its potential for economic autonomy. For the near future, the Great Powers, as well as Israel, need not fear the will and hope of the region’s people: Their conscience has been awakened, but their march towards liberation has been hobbled. History is far from over, but we would do well to meditate on the case of Iraq if we hope one day for a free Middle East.

Ten years is only a brief interval in human history, even while history itself appears to be accelerating and it has much to teach us. The coming liberation of the region’s people will be determined by their capacity to rethink and to overcome the alienation inherited from a captive past. There can be no liberty without memory just as there can be no liberation without awareness of history. The Middle East is no exception.

Tariq Ramadan is professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies in the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Oxford University and a visiting professor at the Faculty of Islamic Studies in Qatar. He is the author of Islam and the Arab Awakening.