In 1960, 13 years after India won freedom, the American writer Selig Harrison published India: The Most Dangerous Decades. He feared “the collapse of the Indian state into regional components” ruled by Communists. Predicting that India would never be able to match China, he wrote: “The West confronts the unmistakable fact of a dominant central authority in China, it is possible that in an unstable India, no outsider will be able to say with assurance where political legitimacy resides.”

Such views were not confined to foreigners. Three years earlier, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari — a confidant of Mahatma Gandhi, and the first Indian governor-general of the country — had predicted that “the centrifugal forces will ultimately prevail”, bringing anarchy or fascism. And my most vivid memories of growing up as one of the midnight’s children generation — born as the Union Jack was hauled down from Delhi’s Red Fort at midnight on August 15, 1947 — are of listening to my parents’ generation, who had survived partition, mournfully surveying the country’s future, some even hoping the British would come back.

Even in 1969, when I came to Britain, India at 22 hardly gave the impression of a young person confident of its future. The country relied on wheat given away by America, and a “guest control order” specified that only 50 people could be invited to parties where food was served. To travel abroad, Indians required the approval of the Reserve Bank — and even then got only £2 (Dh9.57) in foreign exchange. I smuggled £800 in specially made underwear to finance my first year at Loughborough University.

Now in London, I am bombarded by Indian bankers telling me how much more money I would make if I converted my sterling into rupees and deposited them in India. While banks in Britain have virtually stopped paying interest on deposits since the 2008 financial crisis, in India, I can earn around 9 per cent yearly. True, India has not reduced poverty levels as dramatically as China — 250 million Indians live on less than $4 (Dh14.71) a day — but the progress since the British left has been impressive. In 1947, life expectancy was 32, now it is 68; a per capita income of £20 has become more than £5,500; and now India’s gross domestic product of £7.4 trillion ranks it third after China and the United States.

In 1947, only 1,500 villages — a mere 0.025 per cent — were electrified; now 97 per cent of villages have electricity. After two centuries of British rule, only 12 per cent of the population had seen the inside of a classroom; now 74 per cent are literate, with Kerala close to a 100 per cent literacy rate — this in a country with 20 languages. And all this while, every change of government since 1947 has been via the ballot box, with the army not involved — something Greece, Spain, Portugal or even France can’t claim. So why, as it approaches its 70th birthday, is India beset with fears?

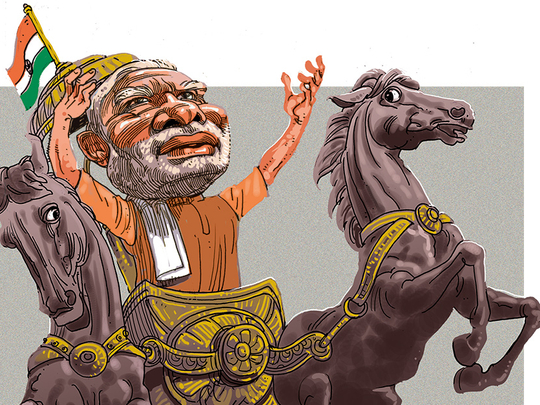

Unlike in my youth, these are not about India breaking up, but the way since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s astonishing election victory in 2014, the country seems to be turning its back on the tolerant, secular society that India’s founding fathers had wanted. Modi has always ridden two chariots: What one prominent Indian businessman, and an old friend of mine, called Modi’s real business of making India prosperous; and his Hindu business of appeasing his fanatical Hindu followers.

Modi came to power on his promise of Acche din — “Good days are coming” — and my friend is confident that Modi will change India for the better, and that the Hindu business will amount to nothing. Yet, Modi has proved a timid reformer, whose tinkering has included an overnight demonetisation that led to such chaos that people died. In contrast, his Hindu followers have been given free rein to believe that Ram Rajya, the mythical rule by the revered Hindu deity Ram, has finally arrived. This has seen a ban on the slaughter of cows, and a growing intolerance of minorities. In Mumbai, the city I grew up in, there is now a form of religious apartheid in housing. Munir Visram, a lawyer, describes how a Muslim client of his wanted to buy a flat in a suburb but, when he gave his name, the broker said: “You are a Muslim. Sorry, this building is not for Muslims. Hindus only.”

Visram says that parts of India’s commercial capital — its most vibrant city — have become so segregated that “owners say this building is for vegetarians only, so no Muslim, Christians, Jews, Parsis or even meat-eating Hindus”. Visram, one of my oldest school friends, is himself an example of the secular India I knew. He is a Muslim, I was born a Hindu. But we were both educated at a Jesuit school, where we prayed to Jesus four times a day. Our shared childhood memory is of the salad bowl of religion and culture that was Mumbai of the 1950s and 1960s, with all faiths living side by side.

Visram is married to a Parsi, and his daughters are married to Hindus. My mother exemplified the religious coexistence of the Mumbai of my youth. A devout Hindu, in her prayer room, she had an idol of Lakshmi, the Hindy deity of wealth. Next to it was a picture of Ganni Baba, a Muslim holy man. Each Thursday morning, we prayed to Lakshmi; and on Thursday evening we bowed our heads in front of Ganni Baba. We asked Lakshmi for wealth; Ganni Baba was for spiritual solace. This despite the fact that both my parents, children of rich Hindu landowners, had been forced to abandon all their ancestral wealth when the India of their home became Pakistan.

The growing intolerance has seen books considered remotely critical of Hinduism or great Hindu heroes banned. Independent India never got rid of the colonial policy of banning books. In 1985, a book of mine on the history of the Aga Khans was banned on the grounds it offended the feelings of the Ismaili community, whose spiritual leader is the Aga Khan. However, the intolerance now being shown seems more widespread. It would be comforting if Indians followed the example of their ancestors.

Back in the 19th century, Indians such as Swami Vivekananda, one of Modi’s heroes, were not afraid to highlight India’s problems and argue about their faith — even against a colonial background in which their rulers would seize on any criticism to justify conquest. What India needs is similar reasoned argument about the type of country Indians want. But on the growing number of television channels, instead of debates there are shouting matches. I got caught in one recently when taking part in a debate about whether India and Pakistan should resume playing cricket, a game both countries love. My argument was that despite India seeing Pakistan as virtually a terrorist state, and Pakistan perceiving Indian rule in Kashmir as colonial oppression, sport and culture can defuse tension.

This was the point that my uncle, a Congress party member of parliament, had made in 1964 after horrific religious violence in both countries threatened war. But I was shouted down. This was on one of India’s most popular talk shows. It is only when Indians manage to rediscover their historic appetite for argument that the glorious dawn — that we midnight’s children were told was our due — will appear.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Mihir Bose is the author of From Midnight to Glorious Morning? India Since Independence.