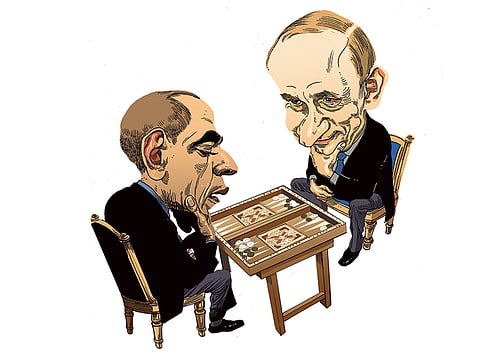

Obama and Putin play games in Syria

Russia and Iran could well agree to dump Al Assad if they get a friendly replacement regime

There is no outlook for peace in Syria as the great powers continue to follow their own agendas and the country divides into a patchwork of independent principalities whose leaders may or may not have any interest in ending the conflict.

This week’s UN General Assembly was a profoundly depressing spectacle for any Syrian hoping to return home, which is why so many have given up any hope of their country coming back and have chosen to make their frighteningly uncertain way to find a new future in Europe and other settled and prosperous countries.

In his speech US President Barack Obama muddled two different objectives. He spoke of the necessity of defeating Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) but failed to offer any new support for the Geneva Two process, which is designed to end the Syrian civil war.

Defeating Daesh is one thing and must include vigorous action in both Iraq and Syria and a strong intellectual counter-attack to marginalise its pernicious doctrines. And this is not remotely the same as gathering all Syrian parties to take part in a peace conference to find a way forward to ending the civil conflict.

Russian President Vladimir Putin persisted in his blind support for Syrian President Bashar Al Assad, presenting him as a vital bulwark against terror while ignoring Al Assad’s role in terrorising his own population, and also helping strengthen Daesh and its predecessors by releasing hundreds of extremist prisoners in 2011 and 2012 in a foolish attempt to split the then opposition.

The debate between the two international powers at the UN was fuelled by the news that Russia has positioned several squadrons of Russian warplanes in its base in Tartous on the south Syrian coast, backed by more than 2,000 ground troops including special forces, which look well able to intervene in the Syrian fighting.

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) commented rather dramatically that “the positioning of Russian aircraft in Syria gives the Kremlin an ability to shape and control US and Western operations in both Syria and Iraq out of all proportion to the size of the Russian force.

“It can compel the US to accept a combined coalition of Russia, Syria, Iran and [the] Lebanese Hezbollah, possibly in support of indiscriminate operations against any and all regime opponents, not just ISIS [Daesh] and Jabhat Al Nusra. It may portend the establishment of a permanent Russian air and naval base in the Eastern Mediterranean. Russian forces have prepared and trained to conduct close air support and possibly special operations in Syria, and may begin doing so within days.”

New era

The ISW took a maximalist interpretation of all this when it stated that “the deployment of Russian military forces in Syria is a major geostrategic inflection. It may well herald a new era in geopolitics and security. Russian forces are establishing an airbase likely to become capable of conducting operations throughout the Levant and Eastern Mediterranean. It would be the first time in history that Russia has an outpost on land beyond the confines of the Black Sea. The US and Nato must consider and respond to this development”.

A more balanced view was put forward by the analyst Orrin Schwab, who said that the Russian deployment was not a major deployment in Syria, pointing out that 2,000 troops is below what the US now has in Iraq and is a fraction of total US forces in the Middle East and North Africa region.

He added that the US uses 17 military bases in Turkey and nine in Afghanistan and according to the Huffington Post, the US has spent $10 trillion (Dh36.7 trillion) protecting the Gulf since the 1970s and has engaged militarily in at least 13 countries in the Middle East since 1980.

Relentless assault

The latest ISW report shows a dramatic reduction in Syrian government-held territory to around 10 per cent of the former Syria, and makes clear that both Iran and Russia are essential to the defence of key government assets like the coastal provinces of Latakia and Tartous, the central cities of Hama and Homs and Damascus International airport, as they continuously degrade under the relentless assault of more than 250,000 rebel fighters.

Back at the UN, an interesting confusion persists between the person of Al Assad and the existence of the Alawite-dominated government forces.

At the UN’s terrorism summit, Obama insisted that Al Assad must go in order to defeat Daesh, while Iran and Russia both supported his continuing in power. Obama will hope this may be diplomatic posturing.

Russia has clear interests in Syria but these do not necessarily need Al Assad personally to be in power. In truth, the Russians need a regime in Damascus that will be Russia-friendly and allow it to have the naval base in Tartous.

The Iranians want a regime that will support and help supply their close clients in Hezbollah.

This analysis means that if the Geneva Two negotiations ever get close to success, Russia and Iran should be willing to help send Al Assad off to a lucrative retirement, if that is the price they have to pay to keep a close relationship with a new Syrian government.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox