Peshawar: Rifaat Ramzan lies in a hospital bed with a blank stare, still traumatised weeks after losing his best friend, Noman, to a suicide bomber.

"He had just told me how it is good to dream and we will achieve our dreams," said Ramzan, who began sleeping with a gun under his pillow, fearful he too will be killed in Pakistan's relentless violence.

"This man came and asked Noman if he could get a lift on his motorcycle to the police station. When they got there the man blew himself up. Noman and nine other people were killed."

In the conflict between Taliban insurgents and Pakistan's army, thousands have been killed in bombings of everything from military and police facilities to crowded street markets; even a volleyball match was attacked. Countless others have been wounded.

But the psychological toll often goes unnoticed, even though underfunded and understaffed hospitals are treating a sharply rising number of people who can't cope with bloodshed.

"This is alarming us," said psychologist Najam Younus.

Some people are too depressed to function. Others are gripped by anxiety attacks, paranoia and post traumatic stress disorder. Flashbacks are common.

It doesn't take much to destabilise minds.

Even headlines of smaller attacks that flash across news channels are enough to send people to psychiatrists seeking pills to calm them or help them sleep at night.

Luckily for Pakistanis, the stigma attached to mental illness has eased, making it easier for them to seek psychiatric care, psychologists say.

Expensive treatment

But the problem is that people caught up in the violence — mostly living in the epicentre of the conflict in the northwest — have no access to psychological care facilities. So they must take long, expensive journeys to cities like Peshawar for treatment.

Those who can afford it often don't get the attention they need because there are too few doctors, who are often overworked and cannot provide therapy, only medicine.

Peshawar's Sarhad Psychiatric Hospital, located on the same complex of a prison where militants awaiting trial and other hard core criminals are held, is one example. It is the only proper mental health facility in the northwest.

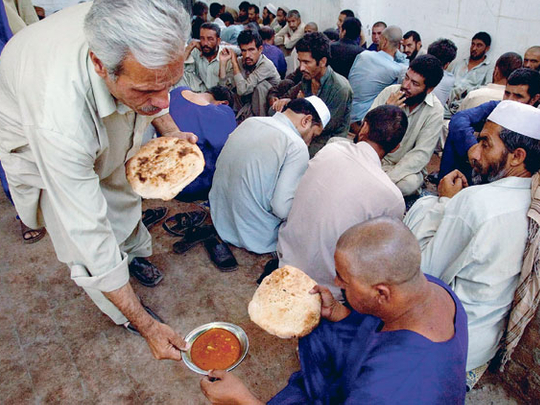

In the hospital courtyard, patients dulled by medicine sit on a cement floor in rows, quietly staring at each other. Some look lost. Others are suspicious.

Senior consultant Mohammad Tariq sometimes treats 100 patients a day. He is also the region's main forensic psychologist, so he must spend time in court. "There is only so much I can do," he says.