The trains get to stop every few minutes. Not the escalators. In a city tied together by its jam-packed subway system, the escalators here just keep rolling throughout the day and also half the night.

There are 643 of them in the Moscow Metro. This is a system with deep stations. At rush hours, fully loaded trains run on 90-second intervals; it is up to the escalators to get the passengers delivered but just as important, to whisk them away again before they start spilling off the platforms on to the tracks.

"In my opinion, they're much more important than trains," Sergei Likhachev says. He would say that, he is the chief mechanic of the Moscow Metro's escalator division. The escalators under his purview carry almost as many people as the trains do — because all but the outermost stations have them — and that can be up to nine million in a single day. Down. And then up. Or 2.5 billion a year.

Continuous run

If a train breaks down, he points out reasonably enough, it gets sent to the yard for repairs. No such luck with an escalator. It has to be fixed in place, and it has to be fixed fast. Without escalators in working order, the Moscow subway system would seize up, and without its subway system, Moscow itself would cease to function.

In fact, all of Russia would feel the shock waves, because some unknowably huge number of subway passengers consists of people trying to transfer between train stations or airports in the capital city, the hub of the nation, so they can get from Novosibirsk to Novorossiysk, or from Velikiye Luki to Ust Usinsk, or from Omsk to Tomsk.

There is an endless river of passengers, who ride more than 64 kilometres' worth of escalators. That is almost a quarter of the length of the rail lines themselves. How do you keep them running? "People," Likhachev says. His division has a staff of 3,000. It has workers posted at every station during operating hours.

It has a 20-member emergency rapid-response team. It also has its own factory churning out spare parts, "so we don't have to rely on suppliers". This is not to say that all escalators work all the time, because they don't. But let's be clear about one thing: "We do not have escalators out of order," Likhachev says. "We close some for repair."

Likhachev, who is 50, studied in an auto institute and worked as a technical translator until that job disappeared, and then tried his hand at car mechanics. But 13 years ago he landed a job with the Metro, on the lowest step of the escalator division, and now he has risen to the top as swiftly as his charges carry their passengers from the depths below to the streets above.

Moscow's escalators, Likhachev says, are in a class by themselves. They are deep — the deepest are at Park Pobedy station, 717 steps long, in one big loop, carrying passengers 230 vertical feet from the platform to a mezzanine, in a trip that takes precisely three minutes.

And they are strong, able to carry 60 tonnes of people, besides their baggage and groceries and purses and umbrellas and gloves. Someone, somewhere, is always dropping something where it will jam in the steps or trying to wedge something on that is too big and heavy or just doing something stupid.

"Unfortunately, the mentality of our passengers leaves much to be desired," Likhachev says, matter-of-factly. And that is where the escalator watchers come in.

A watchful eye on passengers

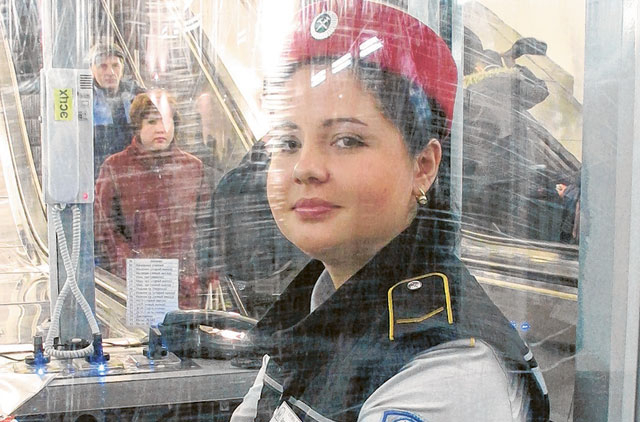

This is a corps of uniformed employees — they are not even in the escalator division — who sit in glass booths at the bottom of all major escalator banks and keep an eye out for trouble. They are almost all women, they are called dezhurnayas and they are renowned for their heart-stopping scowls. A sign on each booth says: "Information is not provided." Do not talk to any of them. Unless you find Ksenia Nevezhina.

She is 18 and has recently started work, at the Belorusskaya station. She hasn't had time to get beaten down yet. She explains that when someone falls or something gets jammed, her job is first to announce quickly that the escalator will be stopping and then to stop it.

Then she instructs passengers to continue walking down or up and summons Likhachev's crew if a fix is in order. "I like it. It's a quiet job," she says. In fact, it is hours at a stretch staring at people going up and down.

She is aware that most of her colleagues, who tend to be considerably past 18 in years, come across as nothing less than ferocious. "Maybe they don't like something about the work," she offers, with a cheery smile. "It's the passengers."

About six years ago, Likhachev recalls, a man took off all his clothes on an escalator. But his last bit of clothing got caught in a step and in turn caught what Likhachev refers to as "one of his parts".

The dezhurnaya on duty stopped the escalator and a repair man approached the ensnared passenger with a large knife. Misunderstanding the employee's intentions, the passenger began yelling: "No, don't cut this!" He didn't. He cut away the tangled clothing instead. Uninjured, the passenger was taken away to a psychiatric hospital. The escalator went back into service.