Dubai: The year was 1964. Alfred Silvester boarded a ship in Bombay (now Mumbai) clutching a third-class ship ticket in his hand. He stood at deck and cheerfully waved out to the crowd of strangers lining the quay. In his mind, this was a short journey he needed to undertake in order to fund his way on a longer journey later to the destination of his dreams — America.

Little did he know that his Big American Dream would never be realised. However, he would end up leading a life far from the US, but it would be a life that would be worth recalling for its many glorious moments, for the opportunity to observe the birth of a nation and the privilege of being in proximity to the father of this great nation.

Silvester’s career in the UAE spans over three decades and it involved a spectrum of duties, from drafting letters to heads of states such as Queen Elizabeth and Indira Gandhi, to playing a pivotal role in the establishment of support systems for Indian expatriates and being involved in countless humanitarian efforts.

Silvester used to be called ‘awwal wahad’ (first one) in the office, he said, due to his employment card number.

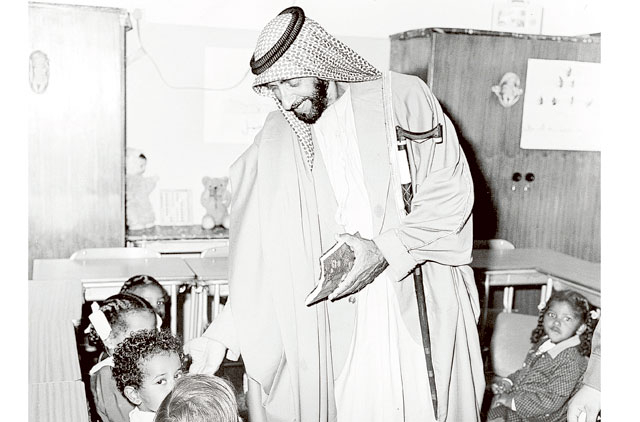

On the occasion of Zayed Humanitarian Day, he walks down memory lane to mark the moments that went into the making of the United Arab Emirates. Visually framing this journey are memorabilia which are worthy of being museum pieces — a labour card that declares him as Abu Dhabi government’s employee number 1, which was issued following an employment order signed by the founding father of UAE, Shaikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan; a gold-plated Rolex watch gifted to him by Shaikh Zayed in 1968, which he wears to date; a rare driving licence issued in 1968 and a passport stamped ‘Trucial States Visa”, which was what it was called prior to the formation of the UAE.

“There was just sand, sand and more sand,” says Silvester, recalling his first impressions of the UAE. “Today, this is a world-class nation and, according to me, the best in the world. It feels like I am in a different place altogether compared to the time I first set foot here,” he recollects in an exclusive interview with Gulf News.

Early years

Silvester’s early years were spent in comfortable conditions. After a privileged schooling, thanks to his family background, he completed his graduation and postgraduation in Economics in Kerala, his hometown, and worked as a college lecturer for a year before moving to Delhi in the 1960s as a research scholar at the National Council of Applied Economic Research.

There, only one dream occupied his mind – a desire to go to the US for a doctorate degree. He managed to get a scholarship at a US university, as well as a part-time job. But there was an obstacle — he needed to have a minimum of $2,000 (Dh7,346 at the present conversion rate) per semester in order for the US embassy to process his student visa. Despite having adequate funds, he could not get sufficient foreign currency “since India was going through a phase of adverse economic policies at the time”, he says.

In order to gather the requisite funds, he needed to look outside India. That’s when his friends advised him to go to the Gulf to secure sufficient foreign currency. After giving it some thought, he decided to give it a shot.

“The plan was to come to Abu Dhabi, since I had relatives there, get enough foreign currency and get on the next flight to the US,” he says.

“I still remember buying a third-class ship ticket for Rs135 (Dh8.24 at the present conversion rate) to reach Dubai, since any higher class ticket would require an income tax clearance.”

“Thus, in March 1964, I left Bombay. There was no one to see me off, but I still waved back at the strangers at the quay.”

The first stop was Karachi, then Muscat, and, five days later, Dubai.

“There was no harbour or jetty or anything at that time,” he says. They had to climb down a rope ladder and make their way to the shore in a boat.

“We reached Dubai on Good Friday. Unlike the plush immigration counters at Dubai’s airports today, back then, there were two officers behind a desk, who stamped my passport with the Trucial States visa.” (The UAE was part of what was called Trucial States by the British and was a British protectorate until 1971.)

“There was no road and not enough water and electricity. The scale of today’s transformation is nothing short of amazing,” he says.

Silvester headed to his relative’s place in Abu Dhabi shortly after he reached Dubai, travelling through the Sabka roads (sand tracks) for several hours. There were just few Land Rovers and helicopters at the time, which were used to rescue people who got lost or perished in the desert, he says. The Gulf rupee (equivalent to the Indian rupee, issued by the Indian government) was still the currency in the UAE (until 1967) back then.

“There were just dried up palm trees here and there. It may have been 45 to 50 degrees Celsius. Empty kerosene bottles were used to transport water on donkeys…but it didn’t come cheap. They were very pricey compared to the cost of living then.”

“Life was primitive… people lived in areesh (palm) huts and used the sea instead of bathrooms. Few houses had electric generators.” Donkeys also transported kerosene and dates.

The first year’s summer almost made him want to go back. “I would head to the beach, take a dip, and make a pillow of sorts with sand and lie down to cool off. For some reason, I decided to hold on for a bit longer and started to look for work.” (The regular visits to the beach ended up making him learn swimming). But his friends discouraged him, warning that there weren’t many jobs for an educated person. “Back then, oil production at Das Island was managed by British Petroleum (BP), who would give one pound to the Abu Dhabi government and keep one pound to themselves, per barrel. Spinneys and African Eastern were in business here too. Those were the limited options.”

He remembers someone asking him whether he could write with that ‘knocking thing’. He was referring to the typewriter. So, he bought one and within a week started to type, at a moderate speed, using just two fingers.

The first job

In the meantime, he became good friends with some Palestinian school teachers in his (futile) effort to learn Arabic and, instead, eventually started teaching them English.

“One day, they had some work at the electricity office and I went along. When we reached, the director of the office had a letter written in English before him. He was trying to find someone to read it out to him since he could not do so.”

His friends introduced him to the director and asked him to help, which he obliged, pleasantly surprising the official. As Silvester was talking to the director, an official from the Lebanese firm, Albert Abela, who got a contract to build an office and accommodation for the Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company, came to meet the director for an electricity connection for their labour accommodation.

The director immediately enquired if there are any vacancies at Albert Abela for Silvester, landing him his first job in the UAE.

The chief engineer, Milham Nasif, was very pleased with his job, says Silvester, adding that it often involved making reports in English, to be submitted to BP, and drafting letters. “I worked very hard and soon became second in command at the office.”

Back then, for all important matters, officials had to go to the palace to seek approval. During one such regular visit, the head of the palace administration asked the chief engineer if he could help in recruiting a well-educated person to work at the palace.

“My boss came back and asked me if I was interested in working for the palace. Who wouldn’t be, if they get the chance, was my response.”

So, the next day, Silvester was taken to Qasr Al Hosn palace.

A British-educated Bahraini, Ahmea Al Obaidli (who later became the Ruler’s Representative in UK and eventually the High Commissioner), was the head of administration at the palace.

“Al Obaidli handed me a letter and asked me to draft a response. I was a bit shocked when I finished reading the letter — it was from the Pakistani President Ayub Khan. I had no experience whatsoever in writing such letters. But I gathered my wits and took a shot at it.”

“After reading it, Al Obaidli asked me to join right away.”

He did end up making one mistake though, Silvester remembers. He addressed Ayub Khan as “His Excellency”. However, later he found out that the phrase used by the palace is “Dear brother in Islam”.

Asked about his salary, he says, “They offered me Rs1,200 per month during three months of probation, and Rs2,000 thereafter.” The average salary at the time was up to Rs500.

It was thus that Silvester started work at the palace in May 1967, not long after Shaikh Zayed came into power, which was in 1966.

Awwal wahad or the First One

It was in the summer of 1968 that the historic meeting between Dubai Ruler Shaikh Rashid Bin Saeed Al Maktoum and Shaikh Zayed took place in the desert, which led to the decision of all the seven emirates to unite forming the UAE.

“I remember people coming and sitting very close beside him [Shaikh Zayed], sharing their concerns and issues. He was friendly and generous.”

Silvester’s job was to take care of all official and private correspondence of Shaikh Zayed with non-Arab countries. Most of it was with the British Empire, regarding routine affairs. The letter he would draft would be translated into Arabic and signed by Shaikh Zayed after verification.

One of the letters he remembers drafting was written by the UAE to the Indian government returning about Rs4 crore (Rs40 million) that was in circulation here, when the UAE stopped using the Indian rupee as currency.

Silvester used to be called ‘awwal wahad’ (first one) in the office, he said, due to his employment card number. “There were about 7,000 civil servants at the time, so I was really lucky to get the card number 1.”

Another memory he has is of his interactions with Shaikh Sultan Bin Zayed Al Nahyan. “He was the first person from the palace to go to the UK and pursue studies,” says Silvester, adding that he was the one who processed the admission papers.

“Shaikh Sultan used to watch me work in my office sometimes when he was young. Once, I told him that I am going to type his name and used his fingers to press the typewriter keys. Then he started repeating that by himself. I was impressed by his smartness.”

Shaikh Zayed’s legacy

“My limitless admiration for Shaikh Zayed lies in his futuristic vision,” says Silvester. “The UAE’s success story is built on the strong foundations laid by the founding father of this country,” he says, his voice choked with pride as tears well up in his eyes. “No ordinary person could dream of transforming this country to what it is today.”

“Shaikh Zayed was not the heir apparent to the throne but he was chosen due to the leadership he displayed while he was responsible for Al Ain,” says Silvester.

“Shaikh Shakbout Bin Sultan Al Nahyan, his older brother, who was ruling Abu Dhabi before him left the UAE when Shaikh Zayed came into power in 1966, with the support of family members as well as the British. But, years later, when he fell ill, Shaikh Zayed brought him back to Abu Dhabi, built a palace for him and cared for him,” Silvester said, adding that these are qualities he cherishes of Shaikh Zayed.

Over the years, many expensive watches were gifted to him as well as to other palace officials by Shaikh Zayed. “But I saved the first one, since it has a lot of emotional value for me,” he says.

“During that time, since there were only about five employees in the palace administration office, we met the ruler every day, greeted him and often ate with him, as well as with his guests, including Shaikh Rashid.” However, these practices changed over the years as the office got bigger, in lieu with the growth and progress of the country.

He recounts an incident that speaks volumes of Shaikh Zayed’s kind and generous nature. “Once when Shaikh Zayed was seated at the majlis, a bit of concrete fell from the ceiling and the same thing happened in the women’s area as well a few days later. The contractor was also present at the time. He quickly apologised to the ruler and asked that he be jailed since what happened was a hazardous situation.”

But Shaikh Zayed forgave him.

Painful farewell

After his career at the palace, Silvester was told that he could stay in the UAE for as long as he wished and it was also his desire to live here all his life but a personal situation in his daughter’s life neccisitated his migration to Canada to be with her. His second daughter lives in London.

“Looking back, I think of the time I first came here and compare it to the time I left — and of the change from a desert into a blooming city, all due to the constant pursuit of Shaikh Zayed in improving the lives of people of his country. I consider it a huge blessing that I was given the chance to be of service to him and see his vision for his country up close,” he says.

- Rayeesa Absal is a Dubai-based freelance writer