Misrata’s strength raises Libyan suspicions

Many believe that the city of Misrata wants to break apart from the country

Misrata: Ask many Libyans how they view the city of Misrata, and their reply often has a note of suspicion: “A state within a state.”

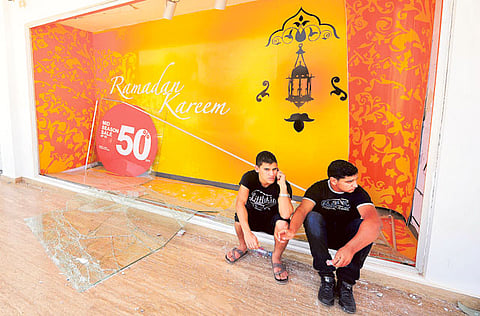

Misratans insist that’s not true. Their city won praise for helping topple Muammar Gaddafi. But now its powerful militias, feuds with other towns, and conspicuous self-sufficiency are prompting questions about its loyalties. Two years after the war, Misrata epitomises a key challenge facing post-Gaddafi Libya: uniting a fractured society.

The city withstood months of siege in 2011 before its militias pushed into Tripoli to help deal a death blow to the regime. It was a Misrata fighter, Omran Shabaan, who found Gaddafi hiding in the culvert from which he was dragged out and executed.

Today, Misrata is poised to rebound from war. It has Libya’s largest port and is expecting a lucrative duty-free zone.

“The plan is for Misrata to be the main trading city in Libya,” says Mohammad Bala, the Libya director for the US-French telecommunications company Alcatel-Lucent and a member of the city’s business council.

And in an unstable country, Misrata is known for order.

“I have checkpoints, and I have people to follow any outsider who enters the city,” says Juma Belhaj, the head of Misrata’s Security Committee, a wartime force whose hundreds of members now act as plainclothes police.

Belhaj and his legal adviser, lawyer Abdullah Al Jerbi, insist the committee answers to Libya’s Interior Ministry. Belhaj also invokes his men’s revolutionary credentials. “Since Feb. 17, the Security Committee has proved itself,” he says, referring to the start of Libya’s uprising. “We’re all revolutionaries.”

Still, some Libyans doubt Misrata’s motives. A portrait of Omran Shabaan at the city’s museum for rebel war dead helps explain. Last summer Shabaan was detained in Bani Walid, a historic rival of Misrata that stayed out of the war. He died of injuries suffered there, and Misratans consider him a martyr.

Misrata militias attacked Bani Walid to arrest his kidnappers. Although sanctioned by the government, the attack looked like a vendetta to some. Civilian leaders in Bani Walid said rocket fire struck civilian areas.

“We heard media talking about how we were attacking families,” says Mohammad Harama, a young Misrata militiaman. “I was shocked. I never saw anything like that.”

What Harama did see was his friend Rabih Sallabi take a bullet while driving their gun-mounted pick-up truck, which raced forward and crashed as Sallabi slumped onto the gas pedal, mortally wounded. “I miss him, but I’m also happy for him,” Harama says. “He died a hero.”

Such incidents have some in Misrata tiring of what they call militiamen’s undue influence.

“They make the rest of us look bad,” says Abdul Hamid, a graphic designer who did not want to give his surname. He longs for a stronger state. “Just once, I’d love a policeman to ask for my papers.”

Abdul Hamid is drinking coffee at a cafe downtown where like-minded young Misratans gather, and which Harama avoids because he fears his role in a militia will get him dirty looks.

Meftah Shetwan, a political adviser, supports a strong central state. But he also hopes that strong local government – in particular, elected councils that can collect taxes and deliver public services – will help bring a sense of normality.

Harama, too, vows his attachment to Libya, but says Misrata takes special priority. “You clean your own house first, then deal with outside,” he says.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox