After Syria, Putin promotes Libyan strongman as new ally

By backing Haftar in his standoff with the government, Russia could secure billions of dollars from Libya in arms

Moscow: Flush with success in supporting his ally in Syria, Vladimir Putin has a new ambition: supporting another one, this time in Libya. The effort is beginning to undermine the UN-backed government there.

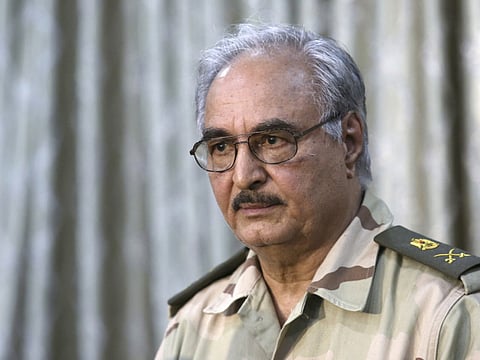

Russian President Putin’s government is befriending a powerful military leader, Khalifa Haftar, who now controls more territory than any other faction in the tumultuous, oil-rich North African state. In two visits to Moscow in the past half-year, Haftar met the defence and foreign ministers, plus the national security chief, to seek support. A top ally also visited last week and Russia is supplying funds and military expertise to Haftar’s base in the east.

“The longer we wait, the more likely it becomes that Haftar wins,” said Riccardo Fabiani, a senior Middle East and North Africa analyst at Eurasia Group in London. “It’s clear he’s getting military, financial and diplomatic support.”

By backing Haftar in his standoff with the government of Prime Minister Fayez Al Serraj in the west, Russia could bolster its role in the region and secure billions of dollars from Libya in arms and other contracts. At the same time, it also risks igniting more conflict in the divided country, where forces loyal to Haftar, as well as rival armed groups, are accused by the UN of human rights abuses including torture and extrajudicial killings.

Other players also support Haftar, though he is opposed by powerful militias mostly across central and western Libya, where 70 per cent of the population lives.

Putin branded the Nato-led campaign that overthrew Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi as a “crusade.”

Russia lost at least $4 billion in arms deals and billions of dollars more in energy and transport contracts after Gaddafi was ousted and killed, according to government and state company officials.

The US and the European Union support the UN-endorsed government in Libya. State Department spokesman John Kirby on November 29 called on Haftar and his forces to submit to “civilian command” of the Tripoli authorities.

Putin’s strategy could cement a new partnership with President-elect Donald Trump, should Moscow and Washington align in backing Haftar’s self-proclaimed fight against radical Islamist groups, according to Mattia Toalda, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Trump has waxed enthusiastic about Egyptian President Abdul Fattah Al Sissi and his proclaimed war on terror.

Haftar, 73, a one-time Gaddafi ally, received military training in the Soviet Union in the 1970s. He speaks good Russian, according to media reports in Moscow. He also lived for two decades in the US after falling out with the Libyan leader, working with the CIA by keeping contact with anti-Gaddafi forces, according to Saudi Arabia-owned Al Arabiya channel.

After returning from exile to fight with rebels during the revolution in 2011, Haftar set up his own power base. He announced a campaign to take control of most of the strategic city of Benghazi in 2014 and in September of this year seized most eastern oil installations.

“You have to work from reality — the key here is military might and control of oil,” said Rafael Enikeev, head of Middle East studies at a Kremlin advisory group run by a former Foreign Intelligence Service general. “In such conditions, Haftar can dictate terms to Tripoli.”

Still, resistance to Haftar in the west of Libya is unlikely to crumble, raising the prospect of continued violence in the holder of Africa’s largest oil reserves. Armed forces from the West backed by US air strikes this month ousted Daesh from its last major stronghold outside Syria and Iraq after a seven-month battle that Haftar’s forces didn’t participate in.

Russia has used its military intervention in Syria to bolster President Bashar Al Assad against rebels backed by the US and its allies, and against terrorist groups. This month, Russian-backed government forces wrested back full control of Aleppo, the former commercial capital, in a major reversal for the opposition in the almost six-year civil war.

While UN resolutions allow only the unity government in Libya to export oil and receive weapons, Russia has friendly ties with Egypt, which is likely sending arms to Haftar and his Libyan National Army, according to Oleg Bulaev, an expert from the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. Al Sissi in May called for Haftar’s military to be allowed to import weapons, the Egypt Daily News reported.

In addition, Russia printed 4 billion Libyan dinars ($2.8 billion) on contract for the Libyan central bank — and transferred it to an eastern city that is loyal to the military chief. The money is being used across the country except for Tripoli and the western Misrata region, a hotbed of anti-Haftar sentiment.

In other ways too, Russia is helping Haftar’s efforts to gain the upper hand over the Government of National Accord. Set up in December 2015, its influence doesn’t extend much beyond the capital. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in Moscow said on December 2 in Rome after meeting his Italian counterpart that Haftar “can and must become part of the national accords”.

A Haftar supporter, Ali Al Tekbali, a defence-committee member of the eastern-based assembly, said that if the stalemate continues, “Russia’s involvement will be inevitable and it will be in support of the legitimate Libyan army that will restore stability”.

That’s not guaranteed to produce the outcome Putin may prefer, according to a report this month by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It noted: “Russia’s support for Khalifa Haftar in the name of countering terrorism could instead escalate Libya’s conflict and undermine the UN-sponsored political process.”

So far, Haftar has allowed oil to flow from the fields and ports he controls and revenues go to the central bank in Tripoli. Wednesday, Libya reopened two of its largest oilfields in the west and began loading its first crude cargo in two years from those fields. But the country’s economy has crumbled amid the continued political stalemate.

One possible outcome of the pressure: the Libyan prime minister could accept a deal in which Haftar would formally recognise Serraj’s government in return for getting full command of Libyan armed forces and becoming de facto ruler of the country, said Karim Mezran, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Centre for the Middle East.

That kind of “militarisation” isn’t the solution, said Ahmad Maiteeq, the deputy prime minister in Tripoli.

Russia’s view is that people like Syria’s Al Assad and Haftar are “authoritarian leaders who are not liberal democrats and are unlikely to introduce democracy in their countries but they can bring order, and therefore we should support them”, said Andrey Kortunov, director-general of a foreign policy research group set up by the Kremlin.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox