Hamra Street in Beirut hasn’t been the same since the civil war struck Lebanon

Efforts are under way to revive area’s once-famous liberal atmosphere

Streets have a life of their own. They don’t just document the march of history, the sound of wars and victories; they also go a long way to establish the culture of a city. Sometimes they are just as popular as the city — who would go to Barcelona and not walk the tree-lined La Rambla or visit Paris and give the Champs-Élysées a miss? And sometimes they take on a persona stronger than that of the city. In Beirut, the one word that encapsulates the spirit of the city and reflects all that is dynamic and inspiring about it is “Hamra”. The street’s golden era began in the 1960s and residents and travellers, who witnessed the blossoming of Hamra and its numerous cafés and art houses, speak fondly of a place that represented not only the progressive ethos of Lebanon, but the finest example of multicultural life in the Arab world. But even postwar Hamra — chaotic and commercial and quite unlike Beirut’s Downtown area or the plushy Achrafieh — has an appeal that is hard to resist. There are almost two different voices you get to hear about what is still probably the most cosmopolitan neighbourhood in Beirut. One that speaks fondly of what Hamra used to be, a place that allured most of the Middle East’s policymakers, playwrights, writers, poets and artists. The other is a more radical youthful voice that still believes in the spirit of Hamra and its potential to remain the face of Beirut.

Always on the move

Lebanese artist/writer Nabeel Abou Hamad remembers Hamra from before (and sometimes during) the civil war as a centre for open-ended debate on political conflicts, social life, economics, culture, literature and art. “I was working as an art director and cartoonist for newspapers and magazines at the time. Hamra was seen as a haven for press people. We would start hanging out in Hamra from around 7 or 8pm and follow up on the latest statements of big policymakers, historians and thinkers of our time.”

For many who lived in Hamra during the 1960s and 1970s, the street was the epicentre of all activities. People would be seen at cafés, restaurants, clothing stores and theatres, eating, shopping, lounging and debating. It was always full of life, always on the move. Cynthia Myntti, professor of public health practice at the American University of Beirut (AUB), says: “Compared to other neighbourhoods in the city, Hamra was more diverse — in a sectarian sense — and more cosmopolitan. Residents included a large Palestinian intelligentsia, many of whom arrived in 1948, and foreign diplomats, bankers and businessmen. The area had Beirut’s fanciest modern cinemas, French-style sidewalk cafés, bookshops and elegant clothes shops.”

Café culture

The cafés in the area, in fact, attracted Arab intellectuals from around the region and encouraged free thought and speech. “Most artists would be at the Horseshoe café,” Abou Hamad says. “It was on the corner of Hamra Street and had the shape of a horseshoe. The cafés would actually start from near the ‘An Nahar’ newspaper office. The first one by the building was called Café Express. Walking down you’d then find the Horseshoe, Café de Paris, Movenpick, Modka, Eldorado, and finally this place called The Strand. We, journalists, would still be up after 2am and we’d walk to the Rauche area, to this place called La Dolce Vita, where we’d hang out until the early hours.” Often said to be the Hyde Park Corner of the Arab World, Hamra was the place where political figures, avant-garde thinkers or democrats would gather wanting to express themselves. “The presence of the AUB helped create an open intellectual atmosphere in Hamra,” Professor Myntti says. “Fayssal’s Restaurant, opposite the main gate of AUB, was a famous meeting place of professors, poets and revolutionaries. ‘Newsweek’ magazine, in fact, dubbed AUB ‘Guerilla U’ in 1970, and the critical, nationalistic ferment from inside the campus walls certainly carried over to the neighbourhood cafés and cultural venues.”

Fadia Jeha, who ran the Ras Beirut Bookshop for many years until the old building was pulled down to make way for a luxury tower, agrees that the presence of the AUB influenced the culture of the street to a certain extent. But, she adds, “Hamra became the most famous street in Lebanon not only because of its proximity to the university but because of its ability to be in line with the demographic, social, cultural and commercial transformations and requirements”.

Jeha, who was raised in Hamra and still lives there, says, “My father came from Al Kora, in north Lebanon … the Hamra citizens were proud to be known and distinguished as the cultured and educated middle class of Lebanon. As a teenager, I felt Hamra was the most beautiful place in the world and I still do believe it was unique. As a “Hamra citizen” I had all I needed within my reach — my home, my school, my friends, restaurants, films, bookshops and theatres. Beirut was on the go 24/7, full of life and energy. We used to feel safe to go around at any time of the night.”

Art critiques

For Abou Hamad, the bygone days were all about debates and discussions. “We actually used to sit down with some of the Arab world’s political figures, who at the time had been exiled from their home nations after military coups or for their liberal and nonconformist ideas. Artists, such as me, would continuously debate and argue about the latest trends in the world of art. It would all happen at the Horseshoe. Part of the group were Paul Guiragossian, Rafiq Sharaf, Jean Khalifé, Mounir Najm, Ameen Basha and others. Nazih Khater, who used to be an art critic for ‘An Nahar’, would sit with the artists and debate. We’d all debate. It was our daily bread. The main debates centred on whether our art should be abstract rather than figurative or international or in keeping with Oriental traditions. Most of the artists could only afford coffee most of the time and I remember the owner of Horseshoe, Monah Dabbaghi, telling us not to hang out at the café during lunch and dinner times because we’d be occupying seats that he wanted to be used by those customers with money to spend on meals.”

The golden period

Ziad Yamut, a resident of Hamra, who is also now an active member of AUB’s University for Seniors, says that his sense of belonging to Hamra has waned over the years. “I was born in 1941 and lived for four years on the third floor of a building in the vicinity of the Commodore Hotel. Around our building, up to Hamra Street and beyond, were agricultural fields planted with vegetables and potatoes in between white berry trees. From our balcony I could see Hamra Street and a few houses scattered here and there. I have a faint memory of the early Forties. I remember watching from our balcony an army parade on Hamra Street being led by a music band. My father said it was the British army liberating the country from the French.”

According to Yamut, Hamra Street started flourishing in the late 1950s with the opening of Cinema Hamra followed by other theatres, the Horseshoe café followed by other cafés, and the Aiglon fashion shop followed by other shops including the famous ABC retailer. These brought other businesses, attracting people from all over Beirut and converting a residential Hamra into a business and tourist hub. New buildings started coming up and offices replaced residential apartments. This was interrupted by the yearlong civil strife of 1958. Hamra Street reached its crescendo in 1975, just before the civil war that started in the spring of 1975 and ended in 1992.

Raw soul of Beirut

Unfortunately, the cultural hotspot of Beirut could not escape the ravages of war. With residents, foreign intellectuals and students fleeing the area, the street lost much of its character. For many of the old-timers the Hamra that rose from the ashes of the civil war is not the Hamra they knew. In one of his interviews to the media, Dabbaghi calls Hamra “just another street … (that) has lost its foreign touch”. Because of the war, Jeha says, most of the “Hamra citizens” left Ras Beirut for other areas in Lebanon or had to leave the country altogether for work. “New cultures invaded the streets surrounding AUB with different tastes and ways of life,” she says.

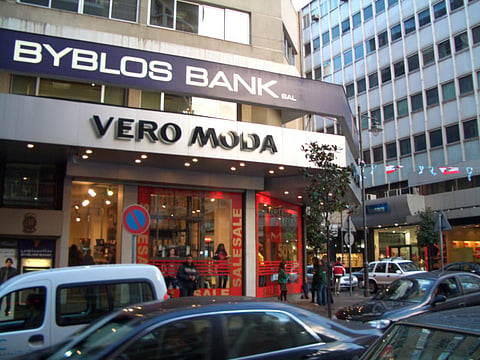

Abou Hamad is equally quick to point out the change: “Every time I go back to Beirut I have a look at Hamra. It’s changed. I don’t see any of the faces I knew. The cafés that were the spring of ideas have since closed down and turned into clothes shops. It makes me feel like a foreigner in my own city. It hurts me. The golden period of Hamra that I knew is gone. Even City Café, which was the last remnant of my Beirut (it was a copy of Horseshoe and run by the same owner), has closed down. I no longer find the friends who used to hang out in the street.” For Abou Hamad the loss of Hamra has meant the loss of friends — writers and poets from other Arab countries, who used to hang out at the Horseshoe, such as Nizar Qabbani, Ghada Samman, Badr Shaker Al Seyab and Abdul Wahab Bayati. These men lived in Beirut for the freedom of expression it offered. Today as Hamra is rebuilt and reborn, these names are missing, but despite that all is not lost. The street, as some would say, continues to be an incredibly lively place despite the traffic, the mix of nationalities, tourists crowding its hotels and modern coffee chains.

Tonnie Choueiri, outreach coordinator at AUB, says, “Youth are drawn to Hamra for its diversity — diversity of people and also diversity of offerings within walking distance, shops, supermarkets and coffee shops. Some of them say that Hamra represents the raw soul of Beirut, without the artificiality found elsewhere. Most of Beirut’s youth don’t know, or ignore, the old Hamra, or know it only through nostalgic accounts of the older generation. Some do aspire to be part of the intellectual café culture long lost.”

Counter culture

While many feel that Hamra has now been eclipsed by Achrafieh and the lavishly built Downtown area, Professor Myntti feels that the street has made a comeback in recent years. “To me Hamra is not at all a ‘has been’ kind of place. What young people are attracted to in Hamra is its counter-culture atmosphere, and it is more relaxed and diverse than Achrafieh,” she says. In the mid-Nineties the Municipality of Beirut gave the street a facelift to attract tourists all year round. There are differences, agrees Professor Myntti, but those differences need to be accepted. “The cafés, for instance, are local franchises of international chains. So instead of Modca or Café de Paris or the Strand, one finds Costa Café, Caribou, Starbucks and Gloria Jean’s. With the exception of our local and excellent Café Younes, the culture of these cafés has changed. One rarely sees newspapers or notebooks in cafés anymore. Laptops and iPads have replaced them. In the past cafés offered coffee, alcoholic drinks and light snacks. Nowadays alcohol is not served in the chain cafés on Hamra. A lot of bars have opened up on neighbouring Makdissi Street. So instead of a more relaxed mixing, we have the new segregation between non-drinking and drinking. What is same, of course, is that much of the conversation is about local politics.”

The Neighbourhood Initiative

In an effort to reach out to the neighbourhood of Ras Beirut (including Hamra), the AUB in 2007 launched The Neighbourhood Initiative that encourages AUB faculty and students to work on issues that concern community members of the area, issues that affect the vitality, liveability and diversity of the district of Beirut just outside the campus walls. The goal is twofold, Professor Myntti says: “To help build and protect an attractive and economically and culturally vibrant neighbourhood, and to enrich the core academic mission of AUB through community-engaged research, teaching and service.” According to Professor Myntti, the Neighbourhood Initiative projects fall under three themes: the urban environment; community and wellbeing; and protecting Ras Beirut diversity. This initiative is the first of its kind in the Middle East. With support from the President’s Office, the initiative has been taken up across the university by its academic and non-academic units, and with a specific geographical focus: the university’s neighbourhood. The university bears the expenses, such as salaries and other operating costs. The university depends on support from foundations and individual donations.

Regaining past glory

“One thing is for sure,” Yamut says, “the Hamra Street community is striving to regain its past.” For instance, as Professor Myntti notes, “While most of the famous old art galleries no longer exist, there are some excellent new ones that offer a real range of art, from very avant-garde to more traditional, such as Agial, Zaman, Art Circle, to name a few. Theatres such as Masrah Al Madina, Metro Madina and Masrah Babel offer a range of cultural activities, local and international plays, music performances and all kinds of dance. The Democratic Republic of Music, located in a wonderfully designed ‘industrial’ basement space is the newest ‘world music’ venue complementing the venerable Blue Note for jazz.”

Yamut is equally optimistic when he says he is waiting to see at least one film theatre pop up on this street. “The area to the north of Hamra Street is developing into a milling hub for the young generation.” The only drawback? “Young hookah smokers in the street cafés,” Yamut says. Another sign perhaps, that Hamra never dies.

BOX:

The Neighbourhood Initiative supports the following activities:

Poetry on the Walls is a student workday in the neighbourhood to paint Arabic poetry and proverbs on walls.

The People Places Exhibition is a student-curated exhibition of student designs for Ras Beirut, covering architecture, urban design and landscape design.

The Neighbourhood Congestion Studies recommends improvements to Bliss Street, improved parking scenarios, innovations in public transportation, among others.

Greening the Neighbourhood is a multipronged project incorporating rainwater collection, composting, green walls and roofs. Prototypes are being built for a local school and local apartment buildings.

The Inclusive Neighbourhood works with the Municipality of Beirut on redesigning Jeanne d’Arc, a major urban artery, making it barrier-free from Bliss to Hamra Streets.

The Ras Beirut Wellbeing Survey is a participatory health and demographic survey of the neighbourhood. A monograph will be published in English and Arabic in 2013.

The University for Seniors is a lifelong learning programme for older adults emphasising peer learning, community building, and inter-generational connections.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox