DUBAI: They are the real-life Ethan Hunt, the Mission Impossible action hero played by Tom Cruise — daredevils who defy gravity and other forces of nature.

But instead of chasing bad guys, these men bust dust, rust and faults in areas that would otherwise be impossible to reach using other access methods.

Unlike Cruise who dangled on a rope from Burj Khalifa for Ghost Protocol — the movie had its world premiere in Dubai on December 7 — no Imax cameras film their feats.

It's a job Daniel Gill, 31, has been doing for the last four years. As business development manager for Dubai-based Megarme, the region's largest industrial rope access firm, the Australian engineer goes with his team of 300 odd technicians to perform unconventional access jobs.

Whether they are installing fireworks up and down Burj Khalifa, the world's tallest man-made structure, cleaning the hood of Metro stations or doing inspections and repairs on an oil rig, it involves working suspended from a rope for hours on end - sometimes up to eight hours a day.

"It's a crazy job. But it's one I enjoy the most," said the Brisbane-born civil engineer whose striking resemblance to the MI4 hero prompts his colleagues to call him a taller version of Tom Cruise.

"One mistake and you're out," said Gill. "I don't fear heights; I respect them." But he admitted getting butterflies in his stomach every time he climbs a tower.

"If you don't have butterflies, there's something wrong... because being nervous causes you to be cautious and thorough. In this job complacency is a killer."

When Cruise's wife Katie Holmes saw the Burj stunt, she said she was so terrified she wanted to throw up. So, does Gill's fiancée, an airline cabin crew, also fear for him? "The first time I went up the spire of Burj Khalifa, I didn't tell her - or even my family because I knew they would be worried. I told them afterwards," said Gill, who manages a smattering of Tagalog and Hindi - his staff are mostly Asians.

According to him Tom Cruise's MI4 feat dangling scene was closer to extreme sports. "We go up there [Burj Khalifa] at least once a year. It [MI4 stunt on the tower] is visually similar to what we do. Obviously, if you're an action hero in a movie, things don't appear planned because you are chasing the bad guys — whereas everything we do is planned and structured."

Megarme, founded 19 years ago in Dubai, has an outstanding safety record.

Gill has been on top of buildings too many to count, loves what he does and can't imagine doing any other job, though he bumped into it somewhat by chance. "My civil construction background helped me into a probationary position and I have not looked back since then."

Megarme's rope access technicians have grown five-fold from 10 in 2003 to 300 today. Gill estimates that the industry as a whole is worth about Dh150 million a year in the Gulf.

A junior technician gets a decent pay, while a senior can earn five figures. The core of the job lies in the rigours of safety training and a zero-tolerance for drugs and alcohol. Technicians keep themselves hydrated by taking a water bag fitted on the back of the harness; they take regular breaks when working suspended in one spot.

While some use robots or cradles to clean windows in high-rises with an even surface, there's still no substitute for men suspended from ropes for jobs such as painting or repairing spires, helipad canopies, podiums and overhangs — or installing fireworks.

Rope access manager Benjamin Cortez, 43, has also lived nearly half his life literally learning the ropes. He joined Megarme at the age of 26: "Of course I was scared. I didn't imagine I would end up in this kind of job. I told myself I'd probably do it for three years, then move on."

But 17 years later, Cortez has established a career in the industry and is certified as a Level 3 technician by UK-based Industrial Rope Access Trade Association. "The first time I was out on a job, it was a very uneasy feeling," said the father of three from Bataan, Philippines. "Safety begins in the mind… and confidence is built through constant practice," he said.

Under Cortez' tutelage, new recruits practise at an indoor facility at Dubai Investment Park for weeks. Afterwards, they are taken to a job site but stay on the ground as support staff.

"It's part of our initiation rites. Sending someone up to do a job with just a week's training is like giving a 16-year-old a fresh driving licence and asking him to drive through the night," said Gill.

Speaking of driving, he added: "It's much safer to be hanging from one of our ropes than be driving down Shaikh Zayed Road."

The rites lead to ties that bind.

"It's like a brotherhood. You have to check, re-check and cross-check your people and equipment. You have to trust the men you work with all the time, every time," said Cortez.

To say that their line of work is interesting is actually an understatement. "I love what I do. It's a wonderful job with elements of everything. It's all hard work — but we actually have a lot of fun," said Gill.

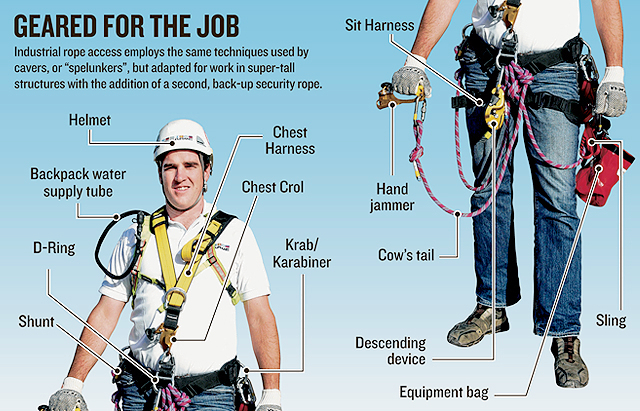

Industrial rope access employs the same techniques used by cavers, or "spelunkers", but adapted for work in super-tall structures with the addition of a second, back-up security rope.