Lahore: One of the most frightening things about Pakistan’s blasphemy law is that the simplest act can spiral into charges that can bring the death penalty. In the case of Aasia Bibi, a Christian woman, it started when she brought water to her fellow women workers on a farm.

On that hot day in 2009, Bibi had a sip from the same container and some of the Muslim women became angry that a Christian had drunk from the same water. They demanded she convert, she refused. Five days later, a mob accused her of blasphemy. She was convicted and sentenced to death. Later this month, the Supreme Court is expected to hear her appeal.

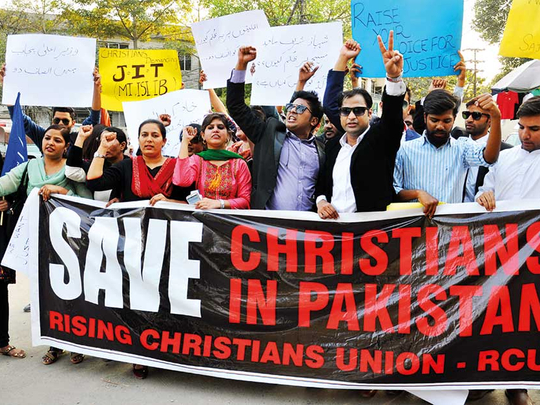

Pakistan is under new international pressure to curb Islamist extremism, and activists at home say one place to start is by changing its blasphemy law.

In January, the US State Department cited the law as one of the reasons as it put Pakistan on a watch list of countries accused of “severe violations of religious freedoms”.

The move came as the Trump administration is ratcheting up pressure on Islamabad, freezing security aid until it cracks down on militant networks operating from its soil to carry out attacks in Afghanistan. Moreover, the Financial Action Task Force, an intergovernmental agency that combats money laundering and terror financing, has given Pakistan until June to show how it will tackle radicalism or else be put on a black list, a step that could hurt its international financial ties.

Opponents of the blasphemy law say it has turned into a force corroding Pakistani society, feeding extremism, implicating the justice system in radicalism and ultimately undermining rule of law.

Often the law is used to punish rivals in personal feuds. Just making an accusation is enough to convince neighbours or others in the community that the defendant is guilty and must be punished, whipping up a vengeful anger even if the courts find the accused innocent. Authorities are often too afraid to push back against the public fury. In at least one case, officials have kept a man acquitted of blasphemy in prison, fearing riots if he is freed.

Militant groups have embraced the law, using it to cultivate support and attack those who try to break their power.

“It has become much more dangerous over the last few years. The reason is that they have created a sense of fear,” said Zahid Hussain, a political analyst and the author of two books on militancy in Pakistan. “It has become a ready tool not only against non-Muslims, but also against Muslims, who do not agree with their world view.”

According to the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, 71 countries have blasphemy laws — around a quarter of them are in the Middle East and North Africa and around a fifth are European countries, though enforcement and punishment varies.

Pakistan is one of the most ferocious enforcers.

At least 1,472 people were charged under Pakistan’s blasphemy laws between 1987 and 2016, according to statistics collected by the Center for Social Justice, a Lahore-based advocacy group. Of those, 730 were Muslims, 501 were Ahmadis — a sect that is reviled by mainstream Muslims as heretics — while 205 were Christians and 26 were Hindus. The Centre said it didn’t know the religion of the final 10 because they were killed by vigilantes before they could get their day in court.

While Pakistan’s law carries the death penalty and offenders have been sentenced to death, so far no one has ever been executed.

A key test will come when Pakistan’s Supreme Court rules on the case of Aasia, whose world was turned upside down after a mob of villagers accused her of insulting Islam and the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) after the water incident.

Aasia’s case even reached the Vatican, where Pope Francis last month met with her husband, Ashiq Masih, and daughter Eisham, who travelled to Rome to witness the Colosseum being bathed in red light in a sign of solidarity with persecuted Christians around the world.

During the emotional encounter, Eisham gave the pope a kiss that she said her mother asked her to deliver.

“The blasphemy law is misused in Pakistan,” Masih told The Associated Press in a rare interview. “It has nothing to do with the Holy Prophet or Islam, it is just to settle grudges.”

He spoke at a small Christian-run school in Lahore which Eisham and a younger, disabled daughter, attend. The school’s principal and owner, Joseph Nadeem, has become a guardian to Masih and his children.

Masih, who said his wife was innocent, points to his arm where a bullet struck him, fired by a protester outraged with his wife’s alleged crime. He never lives in one location too long, because it is potentially dangerous, he said.

Aasia’s lawyer, Saiful Malook fears the Supreme Court will buckle to extremists’ pressure and reject his client’s appeal when it hears it later this month. Her only hope in that case would be a presidential pardon, he said.

Just defending her is dangerous. Malook’s home in Lahore is protected by police. He also is a target because he prosecuted Mumtaz Qadri, the elite police guard who killed Punjab’s provincial governor, Salman Taseer, in 2011, after Taseer defended Aasia Bibi and criticised the misuse of the blasphemy law.

Qadri was hanged for his crime, but he has since become a martyr to millions, who make a pilgrimage to a shrine erected in his name by his family outside the federal capital. Giant posters of Qadri emblazon buildings not far from the school where the AP interviewed Aasia Bibi’s husband.

Fear of being connected with a blasphemy case is so strong that Nasreen Abid, a Christian woman, moved out of earshot of others and whispered as she told the AP her family’s story. She spoke outside Lahore’s Mayo Hospital, where she was waiting to learn the condition of her son, Sajjid, who suffered multiple injuries, including two broken legs, after he jumped from a third-storey window of a police investigation unit.

She said the police called in Sajjid after his cousin, Patras Masih, was arrested on accusations of sharing a blasphemous picture on Facebook. Police wanted to check Sajjid’s phone but found nothing, said his mother.

Then police stripped Sajjid and his cousin, taunted them and told them to have sex with each other, she said. Instead, her son flung himself out the window. Police say they are investigating the incident.

“There shouldn’t be this law,” Abid said. “Now look at us. We shouldn’t be treated like this. We are citizens of Pakistan. We are being treated wrongly because we are poor and we are weak.”

In Jand Wala Saroo, a small village near Pakistan’s border with India, Razia Bibi wonders whether she will ever again see her brother, Mohammad Mansha.

Mansha spent nine years in jail accused of blasphemy until the Supreme Court acquitted him last year, saying the evidence was insufficient. But he remains imprisoned because authorities say his release would start a riot in the village.

“I pray the village will forgive him, but no one wants him back here,” Razia said, sitting on a traditional rope bed surrounded by her many children. “All the villagers are agreed. He shouldn’t come back. Some even said they would kill him.”

Two local men accused Mansha of destroying pages of the Quran at a mosque, though neither witnessed the alleged act. The only purported witness was a child who can neither hear nor speak.

One of the complainants, Allah Ditta Nadeem, told the AP he was at home when people came and told him what had happened. He said he then went to the mosque, where the child explained with hand gestures. Still, Nadeem said he was convinced of Mansha’s guilt.

Hussain, the analyst and author, said most Pakistani politicians privately acknowledge the need to change the law, but are too afraid. Also they often use religious groups when they need them to win elections.

“Neither the military nor the civilian government has a clear strategy how to deal with extremism or militancy in this country,” said Hussain. “For me this is the biggest existential threat to Pakistan because if extremism is not controlled or contained ... it is going to destroy the social fabric of this country.”