Money, men and manipulations

Cosmo Girl believes it is ‘sexy’ to be smart about finances

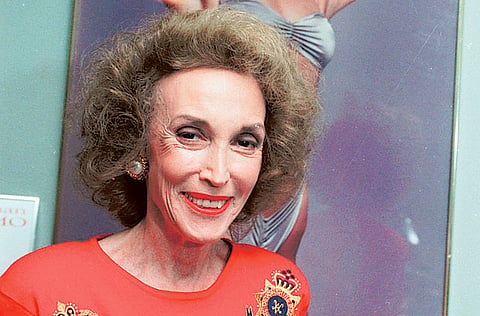

In the week since she died, fans of the legendary Cosmo Girl Helen Gurley Brown have been enthusiastically posting their favourite pieces of Brown’s wisdom online. “If you’re not a sex object, you’re in trouble.” “Marriage is insurance for the worst years of your life. During your best years, you don’t need a husband.” “My own philosophy is if you’re not having sex, you’re finished.” Strangely absent from the single-girl mantras is one of her most significant statements: “Being smart about money,” she wrote in 1962, “is sexy.”

She cared as much about women’s financial lives as she did about their sex lives. In fact, she believed that a healthy sex life depended, at least in part, on a healthy financial life. Paying tribute to Brown as a sort of postwar Suze Orman may seem like a less-than-fun way to reminisce about the queen of Cosmo, but it’s an important part of the revolution she started. “I deal in reality,” Brown liked to say, and the making and spending of money formed a big part of everyday life for her legions of readers.

A child of the Great Depression, Brown learnt early in life that money matters, and she never relinquished her Depression-era sensibility about finances. Her father died when she was 10, and her mother, Cleo, who had years earlier given up her teaching career at the request of her husband, struggled to raise Helen and her sister, Mary. When Mary contracted polio, Helen moved into the role of primary wage-earner. Even though she had been valedictorian of her high-school class, Helen did what many women of her generation did: She went to “business school”, which meant she learnt typing and other skills in the morning and worked at a radio station as a junior secretary in the afternoon. Then, and for years afterwards, she played a vital role in her family but also craved independence; achieving that balance required frugality, not extravagance.

Decades later, as editor of Cosmopolitan, she would admonish her workers, her “girls”, when they spent their hard-earned money on the equivalent of today’s skinny vanilla latte. Why, she would ask, weren’t they putting that money into their bank accounts? In 1962, finances formed an important aspect of Sex and the Single Girl. Brown wanted her readers to be able to live singly “in superlative style”, so they had to learn money management. “It does take money to be successfully single — for clothes, an apartment, vacations, entertainment,” she advised.

Brown knew that her readers’ prospects were somewhat limited. By then, she had worked in enough jobs where she mentored the men who became her bosses to know the frustrations of the glass ceiling. Nevertheless, optimistic to the core, she maintained that even if her readers never earned huge salaries, they could thrive through careful economy. “I have known girls making $100 [Dh367] a week,” she wrote, “who have bailed out their idiot boyfriends who had $25,000-a-year salaries.”

Picture a twentysomething single woman in the early 1960s, one of the most fashion-conscious decades of the 20th century. She was inundated with advertisements promoting the postwar American dream, which she could secure by purchasing shorter hemlines, at-home perms and French perfumes. But her finances were bound to be limited. Most likely, she had a high-school diploma rather than a college degree, and a job rather than a career. Even with a degree, the secretarial pool offered the most financial security, and getting and staying married undoubtedly offered the most promise in the long run. But what if she had the temerity to delay marriage or the audacity to refuse it altogether? What if she had the nerve to want to live, as a single woman, in that superlative style Brown spoke of? What was a girl to do?

Some might think that Brown’s answer would be to manipulate men to do all the purchasing. Wrong. She tried that once, but she found it a ghastly experience. So for her, the answer was simple: Single women had to get smart about money. Brown had countless tips for the financial go-getter. For one thing, every woman needed a bank account, a stock portfolio and the discipline to cultivate savings. “No matter how little money you make, you can live on it ... attractively,” she instructed in Sex and the Single Girl. “Never pay more when you can pay less.”

There were many ways her scrimper could save: Turn out lights, buy medical insurance, negotiate prices when possible, don’t fall for “bargains” that will just stay in the closet, give up smoking, work for a rich man, take extra jobs. “Scrimp on what isn’t sexy or beautiful or really any fun, so you can afford what is,” she wrote. Only two things were non-negotiable for Brown. First, babysitting for extra money was not for the grown woman. “That’s beneath your dignity,” she wrote. And second, women should never buy their own drinks. “That’s no way for you to spend your money.”

If men were going to earn big salaries and prevent women from doing the same, a kind of economic justice demanded that they pay for nights out or nights in — that is, when women invited them in. It wasn’t that Brown didn’t want economic equality for women — she was an ardent supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment — but she had seen enough workplace injustice to believe that if overthrowing the system was one feminist approach, manipulating it was another. For her, the greater a woman’s financial independence, the more likely she was to make decisions about sex, and pretty much everything else, that were right for her. With a bit of money in the bank, a woman was less likely to marry a man who wasn’t right for her. With a healthy life savings, a woman who wanted to avoid marriage could more easily do so. And with a bit of schooling in money management, even the woman in search of a husband was bound to attract a better catch.

Helen Gurley Brown wrote that one of the proudest moments of her life was when, as an advertising copy writer, before she had attained celebrity or significant wealth, she paid $5,000 in cash for a barely used Mercedes-Benz. Although she never considered herself a beauty, she felt smart, accomplished and downright sexy that day.

— Washington Post