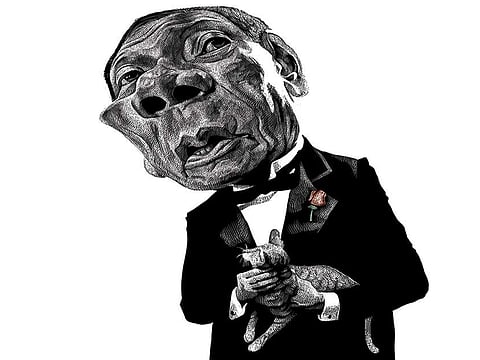

Meet the squadfather

Duterte is about to make the Philippines an offer it can’t refuse, but at what cost?

On Sundays in Davao, a city in the southern Philippines, Mayor Rodrigo Duterte reads a list of names of the people who should leave town or face the consequences, on a TV show called ‘Gikan Sa Masa, Para Sa Masa’, which translates as ‘From the Masses, For the Masses’.

Parallel to this there’s the Davao Death Squad (DDS), a vigilante group that carries out summary executions of those suspected of petty crimes and drug offences. It is estimated that the DDS has claimed over 1,000 lives since the late nineties, some of them children and some of them victims of mistaken identity, according to the Human Rights Watch.

Duterte, a lawyer by trade, now into his seventh term of a 22-year reign as mayor, has challenged those who draw links between his words and the DDS’s actions to prove a connection. It is therefore considered coincidence then that some of those on his televised blacklist have ended up dead.

Quotes, such as the following, haven’t helped distance Duterte’s alleged association to the gunmen however.

“If you are doing an illegal activity in my city, if you are a criminal or part of a syndicate that preys on the innocent people of the city, for as long as I am the mayor, you are a legitimate target of assassination.

“I don’t care if I go to hell as long as the people I serve will live in paradise.”

Davao was known as the murder capital of the Philippines before Duterte took over in 1988. But it now prides itself on supposedly being one of the safest cities in the world thanks to the hard line stance of their 71-year-old defender; a man who is said to drive a taxi around the city after midnight to make sure all is in order.

He now wants to take this no-nonsense provincial model nationwide and this week he became front-runner to replace incumbent Benigno Aquino III in May 9’s presidential elections, profiting hugely from a national outrage over growing crime rates, corruption, and the slow judicial process that aides both.

“I will kill all of you who make the lives of Filipinos miserable,” he has ranted in his often expletive-laden speeches. “If I become president, hide. That number [of those killed] 1,000, will reach 50,000.

“I will have you killed. I will win because of the breakdown of law and order. If I win then beware. The fish in Manila Bay will get fat. I will throw you in there.”

He has also said: “Am I the death squad? True. That is true,” but he later said this statement was to goad his critics into filing charges, and was not an admission.

“There’s no need for you to go to the Ombudsman. There is no requirement that you go to the human rights. File directly in court. Then I’ll place you under oath. Just execute an affidavit.”

Should he win, Duterte would be the first President of the Philippines to hail from the southern island of Mindanao, a hugely important factor given the long-running religious-inspired insurgency in the south-west of the country, which has claimed almost 150,000 lives since 1969.

Previous administrations have failed to find any lasting peace agreement but there remains hope that a president local to the conflict might hold more sway in negotiations, and this is particularly pressing as extremist groups increasingly look towards Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) for inspiration to make their message clearer.

In the absence of strong leadership, Duterte, a motorbike-riding womanising-divorcee who fits the national stereotype of what it means to be a macho Filipino alpha male, is gaining huge support.

He is the old-school father figure who is driven by the greater good no matter what that might take. And for whatever faults he may appear to have, he is considered at least not corrupt. Without living in the Philippines it would be wrong to question the methods behind what needs to be done going forward as circumstances are complex and unique.

However, it remains to be seen how Duterte will project his Davao model on the rest of the country without the more deep-rooted political mechanisms of his rivals who bear the names or backing of the political dynasties, like that of the Aquino and Marcos families.

Even if he does achieve this on a national level, there’s the not-so-small matter of how his persona might be received internationally.

Beyond just the heightened scrutiny of his alleged links with the DDS, there’s also the fear of what he might say to ignite already sensitive relations with China over the disputed Spratly Islands.

Out of all the candidates, it is no doubt Duterte appears to hold the best answers, but that still doesn’t mean those answers are right.