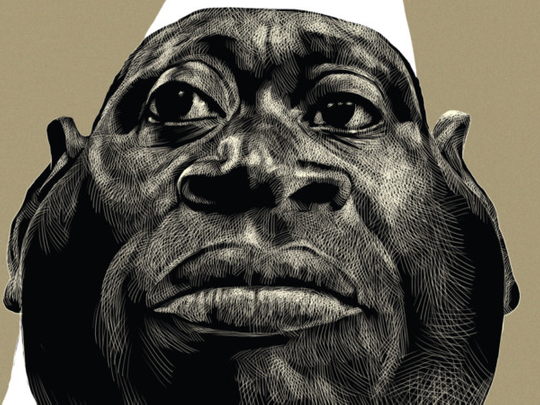

He claims to have found a herbal cure for Aids. It is rumoured that he ordered the brutal execution of nine political figures because a witch doctor warned him of an imminent coup, and urged him to ward it off through human sacrifice. In a live television address, he threatened to kill those who collaborate with human rights activists. Such is the world of “His Excellency Shaikh Professor Doctor President Yahya Jammeh”, the dictator of Gambia, and one of the few remaining “Big Men” of Africa.

Jammeh came to power through a time honoured African tradition: the military coup. He was a 29-year-old army lieutenant when he seized control of the tiny country in 1994. And ever since, Jammeh has tried to remake Gambia in his own image. He has “won” four elections, says he wants to rule for thousands of years, and reacts violently when chided for such comments. In fact, after “winning” the 2011 elections with a big margin, he did not rule out becoming king. His cronies campaigned throughout the country to make him a monarch. The president only backed out after widespread derision.

While Gambians have had to live with him for a while, Jammeh only gained international notoriety in 2007 when he claimed to have found a herbal cure for Aids, the global scourge that has taken a particularly heavy toll in the African continent. When the UN representative in Gambia cast doubts about his claims, he chucked her out of the country. Jammeh, who said he can also cure asthma, made his Aids announcement to a gathering of foreign diplomats.

“I can treat asthma and HIV/Aids ... Within three days the person should be tested again and I can tell you that he/she will be negative,” he said in a statement.

“I am not a witch doctor and in fact you cannot have a witch doctor. You are either a witch or a doctor,” he added.

His claims were, of course, fully backed by his then health minister, Dr Tamsir Mbow. “I was filled with joy and happiness when the results came out, showing and proving the effectiveness of the president’s treatment. With those results it was a proof to the whole world that finally a cure has been discovered. It also meant that President Jammeh had picked up a huge global fight on behalf of the Gambian people and humanity at large in the form of treating HIV/Aids.”

The doctor went on: “I could see the love and sympathy that he has for his patients. He is very passionate with his patients. He cares for them a lot. All patients who have undergone his treatment really appreciate the help and love he showed them. Thousands of people have benefited from the treatment. Many are now aware and convinced about the treatment. They know that there is a cure, and there are more patients now than before.”

One of Jammeh patients, Ousman Sowe, told the BBC in 2007: “I’ve noticed I’ve increased weight substantially over the last 10 days. I am no longer suffering from constipation, but we have yet to receive result of the tests … I have 100 per cent confidence in the president and I’m taking the medication with all confidence.”

A leading Aids specialist, Dr Jerry Coovadia of South Africa, said about Jammeh’s cure: “I’m astonished. The danger of a president standing up [to say this] is shocking.” He said that it was tragic Gambia had a “political environment that allows a minister of health and a president to violate every foundation of science and public health”.

“The entire exercise is circumscribed by secrecy — that’s not how science works,” he said in an interview to the BBC.

The tragedy is that apart from being outlandish, Jammeh’s controversial “cure” may have led to an increase in risky sexual behaviour among Gambians and/or forced them to undergo his treatment — thereby endangering their lives – instead of taking the standard retro-viral drugs that are administered to Aid patients globally.

Another problem that caught the president’s attention was the prevalence of witches in his country. In 2009, on a whim, he ordered the rounding up on hundreds of Gambians. They were picked up from their villages and driven in buses to secret locations where they were orally administered a vile concoction. Many reported to have experienced hallucinations long afterwards. According to Amnesty International, some actually died as a result of the bizarre crackdown.

To be fair to Jammeh, Gambia has enjoyed continued stability — a rare phenomenon in West Africa — under his iron clad rule. His government has long depended on foreign aid — mainly from Europe — to finance it is welfare programmes. But Jammeh refuses to acknowledge that. “Those who say the Gambia has been built on foreign aid let them show you one infrastructure here that was built with foreign aid,” he once thundered. “They have never given me a respite, they have been attacking me all the time because of my stance on important issues, which will never change, and then they go ahead and report that the Gambia’s success story is due to foreign aid. Foreign aid from which Western country?”

Increasingly, however, Gambia has emerged as an exotic getaway for European, especially British, travellers who are attracted to the country’s long, unspoilt coastline. They bringing in much needed tourist dollars.

Jammeh has also brought a measure of development, with new schools and infrastructural development. But this has come at a price.

The political opposition has experienced a ruthless crackdown in the course of Jammeh’s rule. The mere mention of the “Mile 2 Hotel” jail on the outskirts of Banjul, the capital, sends shivers down the spines of ordinary Gambians. It is here that those perceived to be opponents of the regime are imprisoned. Horrific torture is the norm and death through diseases is not uncommon.

In August 2012, Jammeh put an arbitrary end to the country’s 27-year-old moratorium on the death penalty and ordered the execution by firing squad of nine political opponents, including a woman. They were accused of “treason”. Considering that opposing the president in any form can be considered treason in Gambia, the executions were roundly condemned internationally. Two of the victims were Senegalese, and the government in Dakar was not even warned in advance of the executions.

The worst part was that there were consistent rumours in the capital, even in the diplomatic circles, that the president ordered the executions not because of a perceived political threat from the victims but because a witch doctor had warned him of an impending coup, saying that only a human sacrifice could ward off such an eventuality.