It might be a small country in size, but when it comes to food, Syria offers a huge choice. Mike Harrison, the nomadic foodie who has spent several years researching flavours of various Middle Eastern cuisines, this time brings you the rich tastes and aromas of this beautiful country.

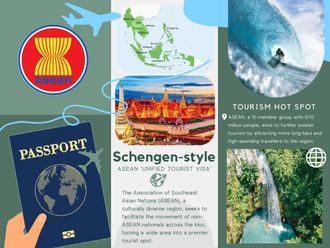

Damascus beckons! With Air Arabia, the low-cost carrier, now serving three Syrian destinations from Sharjah International Airport (Damascus, Aleppo and Latakia), there has never been a better time to explore this country which has such a vibrant and rich history.

Syria has long been a favourite summer destination of Gulf nationals, but has generally remained a little off the beaten track for Western visitors compared to its neighbours of Jordan, Egypt, Turkey and Lebanon.

Ironically, it is perhaps because of the absence of large numbers of tourists, that the country and its people reserve a unique welcome for those who take the trouble to visit.

I have warm memories of my only visit to Damascus, all of 25 years ago! Slightly intimidated and in awe of a city with such an incredible history, I was also enchanted by the hospitality of the people and the atmosphere of the place in general.

I spent many happy hours sitting under a mulberry tree in a courtyard near the ancient Umayyad mosque, writing postcards and people-watching.

And trying to come to grips with my potted history of the city.

Damascus is known to be probably the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. There is firm evidence that in the 3rd millennium BC it was a population centre of a civilisation that was extremely prosperous and influential.

The actual documented history of the city begins in the 2nd millennium BC, when Damascus became the capital of a small Aramaean community.

The Aramaeans spoke an early dialect of Arabic, later called Syriac or Aramaic, and settled in Damascus due to its fertile soil and proximity to sweet water.

A possible etymology of the name of the city is 'Dar Meshq', or 'well-watered place'.

The names of the invaders, conquerors, rulers and inhabitants certainly trip easily off the tongue, since they are, for me, names embedded in my schoolboy mind, all reminding me of my fascination with Middle Eastern history since my school days: from the Assyrians to the Chaldeans; King Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians, via Persian dominance under Cyrus through the Nabateans and the Roman conquest just before the birth of Jesus Christ; the annexation of Syria by the Roman General Pompeii and the blossoming of the city under Roman and Byzantine control, when Damascus gained a significant economic importance as the crossroads of the East and West, and Damascene swords, glassware and cloth became renowned throughout the Empire.

Following the decline of the Roman Empire, it was briefly back to the Persians, followed by the Byzantines, and then the Umayyad dynasty. In 635 AD, Muslim armies under Khaled Ibn al-Walid entered Damascus and annexed Syria to the quickly expanding Muslim empire.

The Umayyads were followed by the Abbasids, the Fatimids, the Seljuks and the Atabegs, the Memluks and finally, in the four centuries prior to independence, Damascus was under Ottoman occupation.

So, with that brief potted history out of the way, let's get back to the main focus of today's story: the road to Damascus, and more importantly for me, the gastronomic journey which takes us there!

I recall that on my first day in Damascus, back in 1981, I ventured into the warren of tiny streets and alleyways which have formed the souq for more than two millennia. It is a 'real' souq, relatively untouched by touristic artefacts, and full of colour, smells, sounds and textures.

There were plastic pots and other kitchen appliances, electrical items, blankets, clothes, fruit, vegetables, spices, candles, shawls, ghutras, stationery, brassware and prayer mats. I was so fascinated that I got completely lost in the place, and spent much of the day trying to find my way out!

Embarrassed to ask my way because of my unconfident Arabic, it took me hours before I finally recognised a landmark and staggered back to my hotel, slightly traumatised, but exhilarated.

Then the next day, I plunged right back into the warren of streets and promptly got lost again, but had a whale of a time discovering little courtyards, hammams and mosques.

To get a sense of Syria in 2007, I have prepared my usual gastronomic tour for you. However, before presenting today's food, I wanted to get a different, contemporary flavour of the city, and have done this with the help of a good friend and colleague, Kate, who recently returned from a trip there.

Syria is not THE most obvious holiday destination for a single woman traveller, although perhaps a good tradition was established by Gertrude Bell, the intrepid English explorer and map maker ('the queen without a crown', as she used to be known by Iraqi friends of mine), of the early 20th century.

Making no prior plans, and going at five days' notice, Kate felt a certain trepidation setting out on her trip, but only because of her lack of Arabic. She envisaged pottering around ruins and not communicating much with locals. She could not have been more wrong.

The first thing Kate remarked was the gallantry, kindness and respect which she encountered everywhere. People were at pains to assist in any way, and she was inundated with discrete, yet not insistent, hospitality.

Communication was warm and sincere, and she lost count of the offers of roadside juices and meals that she received. It also seemed that everyone wanted to practise their English on her!

After brief visits to Aleppo, the Euphrates and the historic ruins of Palmyra, Kate was smitten by the country, and vowed to return at the earliest opportunity for a fuller visit.

Naturally, I was also eager to get Kate's impressions of the other flavours of Syria, since Syrian food, like Lebanese, is globally renowned.

The streets of Damascus offer something for all palates, from their best known exports of hummus, moutabel and creamy labneh, through to the delicious aroma of grilled meat (not Kate's favourite, unfortunately, as she is vegetarian), always best served at the roadside!

Residents of the city enjoy late meals after an appetite-building, Mediterranean-style promenade, and the evening meal is a leisurely affair, starting off with cold plates of flavoursome dips mopped up with Arabic bread, crispy fresh salad leaves and cucumber, and calorie-filled, aromatic fatayer and sambusek.

Alongside juices of fresh mulberries, pomegranates and oranges, there might also be plates of thinly-sliced Armenian pasturma, hot chicken livers or kebbé balls.

For today's feature, I decided to seek out something a little different. Little is mentioned of the Armenian diaspora, another community which has spread throughout the Middle East - particularly in Lebanon and Syria - and left not an insignificant stamp on regional culinary traditions.

The Armenian salad in the feature is not significantly different to any other salad found from Athens to Shiraz, yet is perked up somewhat by the addition of distinctive ingredients such as grated lemon rind, fresh mint and a deep crimson chilli pepper (optional!).

The beurek is a basic dish that the Ottomans were responsible for carrying with them to the Balkan area hundreds of years ago and which I've eaten in Albania and the former Yugoslavia.

A version of today's recipe, from Aleppo, can be found in my book, From Tagine to Masala, the 2nd edition of which has just been published in Dubai.

Beurek is delicious eaten hot or cold, especially when served with a green salad and makes for a very practical and tasty addition to a picnic if you're planning a trip up a wadi in the near future. If using feta cheese, make sure to select a low-salt one.

Another Ottoman-influenced dish is the 'Tabakh Roho', meaning 'Tasty Feeling', and one which Chef Wail Al Khulef, who prepared it for me, informs me that is particularly popular among the elderly, as it's a substantive dish, bursting with flavour, and requires no chewing!

Chef Wail was also responsible for the maqluba, a creative dish also well-known in the Gulf region, which involves cooking together meat, vegetables (cauliflower, or eggplant in particular) and rice, in layers, and then turning out the finished product 'upside down', which is the meaning of the Arabic term, maqluba.

Another dish, popular especially in winter, as it also makes a refreshing change from rice, is fareekah, or pearl barley. An Aleppo version would include a chilli sauce to spicen the dish up.

To finish off our Syrian meal, I should really offer some pieces of sticky baklava, or ma'amoul, soft pastries stuffed with pistachios, and particularly popular at 'Eid.

But the cake which my friend June Brown (another seasoned, nomadic English teacher) kindly offered to prepare, is one that actually caught my eye on the internet, and although it seems rather labour-intensive, it proved to be extremely moreish, and definitely worth the effort.

Sahtein! Bon appetit!

Thanks to the team of Chef Jan Seibold (and Junior Sous Chef Wail Al Khulef in particular) of the Muscat Crowne Plaza Hotel in Oman. Also, June Brown, who prepared the Beurek, and Halva Cake, always best made at home. Kate Tindle provided the travel photos and inspiration.