A dimly lit empty parking lot on the outskirts of a city wasn't the kind of setting in which I ever expected to find a pack of wild hyenas - even if I was in Africa. Seeing them emerge from the darkness of the sparse woodland, the noise of their paws on the sandy ground barely audible, was a surreal experience. Snub-nosed, barrel-necked and with disproportionately large eyes that glow an eerie pale blue in the moonlight, the hyena is a peculiarly unattractive animal. It's not hard to understand why in African mythology it is sometimes portrayed as a symbol of depravity.

It was my first night in the Ethiopian city of Harar, an energy-sapping ten-hour bus ride from the country's capital, Addis Ababa. I had come here to witness a nightly ritual that stretches back several decades to when the region was hit by famine and hyenas living on the outskirts of the city began to attack the townsfolk. In a bid to appease the animals a few of the city's inhabitants began feeding them porridge after sunset. Over time the hyenas became less wary of humans and allowed themselves to be fed at close range. Close enough, that is, to smell their repellent breath - a rancid amalgam of rotting meat and wet dog.

A photo of yourself feeding hyenas strips of meat wrapped around a stick held between your teeth has become the ultimate Harar souvenir. It's what lures most of the younger tourists, particularly back-packers tired of the Asian hippy trail, to the city. Evidently the chance of being photographed nose-to-nose with one of Africa's largest carnivores, and thus trumping their friends' Facebook pictures of Goan beach parties, Thai ladyboys and cute koala bears, is irresistible.

The best-laid plans…

Before coming here I had planned to observe this ritual from a safe distance - ie, several metres away and preferably from the inside of a car. Hospitals in Ethiopia are sketchy, even in Addis Ababa, so the idea of needing medical treatment after getting mauled by a rabid wild animal in this remote part of the country was, frankly, terrifying.

My fear began to abate, however, when Mulagata, one of the city's two hyena men, began to feed them strips of camel meat and offal from a straw basket as casually as if he were tossing a biscuit to a beagle. Encouraged by Sisay, my trusty guide - "You try, no problem, very safe" - I soon found myself handing him my camera and cautiously took my place next to Mulagata. In his elaborately patterned orange shirt, he looked like the grand master of some kind of tribal ceremony.

I watched as he placed in his mouth a short stick with a strip of raw camel meat hanging from the end. Immediately, the biggest of the hyenas sprang forward and snatched the meat, skulking back into the darkness to devour it. Mulagata repeated this several times. And then, at last, it was my turn.

As I clamped the stick between my teeth, five circling hyenas hungrily eyeing the offal, all I could think of was whether I'd be eligible for free reconstructive plastic surgery on the British National Health Service if things went a bit pear-shaped. It certainly wasn't the adrenaline-pumping moment of primal fear I'd been expecting. A snap of a jaw, a tug on a stick, a whiff of hyena halitosis and it was all over. Grinning, Mulagata stood before me, holding out his hand for the 100birr (Dh21) fee. "Good, very brave," he said, unconvincingly.

An assault on the senses

This nightly urban wildlife show is a fraction of what Harar has to offer tourists. The day after my hyena encounter, Sisay took me on a guided tour of the city, which required a sturdy pair of legs, a couple of short rides in a rusty auto-rickshaw (or "bajaj" as the locals call them) and a monumental capacity for wonder.

Harar is a tiny city divided into two distinct parts. Outside the ancient walled town the air is a fusty cocktail of dust, exhaust fumes and stale urine from the lack of a proper sewage system. Brightly painted shops selling cheap mobile phones and Chinese-made clothes line the streets, while dozens of sparsely furnished cafés sell arguably the best coffee on the continent (Ethiopia is, after all, the home of the coffee bean).

On the outskirts of the walled town, hundreds of women in traditional garb sit at the roadside selling sacks of khat leaf - eaten in huge quantities in this part of Ethiopia and Somalia. Evidence of lives ruined by a dependence on khat - a legal amphetamine-like stimulant- is everywhere. Men with a manic gleam in their eyes and green-tinged teeth dance in the middle of the road, their limbs jerking away like an epileptic Mick Jagger as the auto-rickshaws swerve to avoid them.

Harar is a place that incessantly batters your senses and demands that you adopt a constant state of vigilance. It's not that the Harari people aren't friendly and welcoming - they are - but there is so much going on around you all the time.

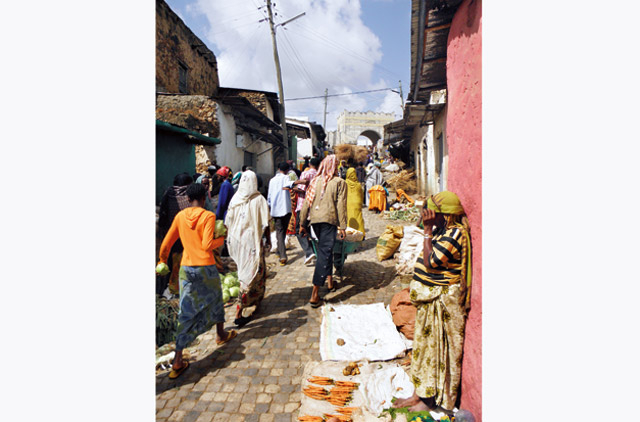

When finally we entered the ancient walled town (368 labyrinthine alleyways packed into just one square kilometre) I was more than ready for its comparatively quiet streets and cleaner air. With its winding alleyways, cobblestone roads and concentration of tiny mosques, this part of Harar is frequently compared to Fez in Morrocco. Still, it's impossible to get lost. Every road eventually leads to one of the six entrance gates to the city.

For centuries Harar was an important commercial hub where wealthy merchants from Africa, India and the Middle East flocked to do business. In the 17th and 18th centuries it became known as an important centre of Islamic scholarship, while according to UNESCO it is considered the fourth holy city of Islam. It's doubtful there is anywhere else in the world with such a high concentration of mosques - 82 at the last count - as well as numerous shrines and tombs. Among them are eight churches serving the Catholics and Christians who make up five per cent of the walled city's population of around 25,000.

When I asked Sisay, a Catholic, whether there was any friction between Muslims and Christians he laughed and said never. As if to prove a point, he said he would later take me to the home of his childhood best friend, a Muslim, where we would drink coffee.

Stepping back in time

As we strolled around the walled city, the alleyways a haven of tranquillity compared to the raucous bustle of the market outside, I attracted the attention of dozens of smiling children. They shouted ‘ferenj!' (foreigner) at me, playfully darting out of sight when I responded with a wave and a "Seulam" (Amharic for "hello"). The bolder ones held out their hands for money, sweets or pens. Tourists remain something of a novelty in Harar. According to Sisay the city receives barely 50 foreign visitors a week.

The 21st century felt very far away on the streets of the walled city. Tailors, blacksmiths and butchers use the same working methods their forefathers did centuries earlier, while untethered donkeys and goats wander idly around streets that are too narrow for cars. They never go missing, Sisay assured me. The sense of community is strong and everybody knows what belongs to whom. Goats, donkeys, even children all find their way home by sunset.

I asked Sisay to take me to the Rimbaud House, named after the wild-living French poet Arthur Rimbaud - the Russell Brand of his day. While it is not widely believed he lived in the house now dedicated to his poetry, Rimbaud's stay in Harar for several years in the late 19th century is well documented. Weary of his licentious lifestyle, Rimbaud fled France in 1875, aged 21, to see the world. After stints in Java, Cyprus and Yemen he ended up in Harar, where he ran guns and traded coffee before returning to France in 1891, his body ravaged by cancer. The museum was closed when we arrived but it is said to contain illustrated panels about his life and a photographic exhibition of Harar at the turn of the 20th century.

Rimbaud wasn't the first westerner to visit Harar. That honour goes to the British explorer Sir Richard Burton who in 1854 disguised himself as an Arab merchant to penetrate the city, which at that time was strictly off-limits to Christians. Burton's fluent Arabic allowed him to go undetected, although some say his identity was known all along and he was tolerated by the city's rulers as a figure of intrigue.

At sunset, Sisay took me to the home of his best friend for an evening of coffee drinking and khat chewing. In the absence of any nightclubs, bars or cinemas, this is what passes for entertainment in Harar.

Earlier Sisay had stocked up on coffee beans and several bundles of khat as a gift for Sofien-Abdullah, a lecturer in electronics at a local college. His house, a one-story building with a tiny high-walled yard, was in the heart of the old town. He and his wife welcomed me into the sitting room, which had no furniture as such, only an elevated floor area covered with a carpet and intricately patterned hand-made cushions - a typical Harari home.

There were framed verses of the Quran on the walls and an old portable TV in the corner. Their one-year-old daughter played contentedly as I answered their questions about life in Dubai. When I told them how much it cost to rent my one-bedroom apartment they were horrified. Sisay, clearly averse to big cities, told me he had been to Addis Ababa only twice in his life, and that was more than enough. He had no plans to leave Harar. His ambition was to save enough money to buy an autorickshaw.

I watched as Sisay and his friends munched their way through a carrier bag-full of khat. For something that supposedly gives you energy and a feeling of euphoria they seemed strangely relaxed, lethargic even. Sisay showed me how to pull the leaves from the stem and flick them to get rid of insects. I wasn't surprised to learn that khat is an appetite suppressant. For several hours they ate nothing else.

It was the perfect way to end my last night in Harar, an otherworldly place that, if you're prepared to go with the flow, can provide the most magical of experiences to the most jaded of globe-trekkers.

Waiting for the coach back to Addis Ababa at 5am the following morning, thoroughly exhausted, I found myself at the bus station with a contingent of nuns who had been visiting a Catholic orphanage."You see the hyenas?" one of them asked. I told them I had already fed them and had pictures taken with them. "No, do you see them now?" she said, pointing across the unlit street.

And then I saw them, several feet away, three hyenas, the blood-matted fur on their sloped backs glistening in the moonlight as they silently scoped out the street for scraps of food. The hyenas of Harar, come to say goodbye.

How to get there: The Selam bus departs for Harar each morning at around 5am from Meskel Square in Addis Ababa. The buses are fairly modern and comfortable and refreshments are included. A one-way ticket costs 250birr (Dh55). www.selambus.com

Where to stay: The centrally located Belayneh Hotel (0256 662030) is excellent value for money with rooms starting from around 150 birr a night, although you might encounter the odd cockroach and don't expect a constant water supply. The Heritage Plaza (330birr, 0256 6665137) is spotlessly clean but is out of town.

Flying to Ethiopia: Emirates Airlines flies direct to Bole International Airport, Addis Ababa, from Dh2300.