The development of Algerian nationalism may be traced to the post-First World War period, when an estimated 300,000 Algerian workers and soldiers fought with the French but were denied any rewards for their heroic actions. Remarkably, many of these brave men represented themselves as French Muslims, believing in the educational rhetoric they were served through France's Mission Civilisatrice (Civilising Mission, that stood for a policy rationale for colonisation).

Despite their moderating influences, colonial authorities and French settlers perceived them as revolutionaries, even if what most wanted immediately after the war was equal rights. In 1918, almost no one was talking about independence as most nationalists wished to create more effective assimilation mechanisms. Al Hajj Ahmad Missali (1898-1974) was one of the exceptions to this rule and quickly became a hero to his countrymen.

Liberal reform movements in Algeria

Disappointed by the French, many Algerians, who had placed their hopes in the Front Populaire by relying on French socialists in their assimilation policies, believed that serious reforms would materialise. In February 1939, the French communist leader Maurice Thorez advocated assimilation when he characterised Algeria as "a nation in formation in the melting pot of twenty races" even if the French Communist Part (PCF) supported full independence.

Comically, Paris entrusted responsibility to a civil servant, Maurice Viollette, for Algerian affairs as the latter drafted a plan that offered French citizenship to about 25,000 Muslims, without requiring them to renounce Islamic law. (Parenthetically, and in light of present debates on Islam in France, it may be worth recalling that an Algerian could become a French citizen before the Second World War if he or she renounced Sharia, which effectively meant renouncing Islam. Needless to say, very few took advantage of the offer, even if many joined the French military after a law established their right to serve France's "Army of Africa").

Importantly, while the Bill eliminated the incompatibility of religious identity with membership in French society, it was intended as a moderating approach to assimilation. Caught in the whirlwind of workers' movements throughout France — and the rest of Europe for that matter — were a number of Algerians who quickly joined local communist parties.

Most rejected so-called assimilation planks and believed that neither equal rights nor citizenship would be extended gradually and over time to the rest of the population as the Viollette plan implied. In the event, the Bill was ultimately defeated in the French Senate in 1938 and while it was disappointing to proponents of equality and reform, the failure was an omen for Missali's nascent nationalist movement.

Missali stood as one of the most active Algerians among a group of immigrant workers and students living in France. He quickly understood that the ultimate goal was nothing short of independence and, starting in 1926, joined the PCF, where he built close relations with senior members.

Led at first by Ali Abul Qader, the Étoile Nord-Africaine (North African Star) started as a social action, Marxist-oriented, anti-colonial movement in 1926 with support from the PCF. At the time — and this much ought to be reiterated — this group was the only movement to demand a future for Algeria without France.

Not surprisingly, Missali's activities landed him in jail as he was imprisoned in 1933 for repeated incitements to violence. He was released in 1935, when he sought refuge in Switzerland, which was one of the more fortuitous stops in his career. It was around Lake Geneva that Missali met Shakib Arslan (1869-1946), an exiled Lebanese Druze leader who influenced and directed the Algerian towards a nationalist, rather than a Marxist, course.

Arslan was one of the more enigmatic Arab leaders of the 20th century who genuinely served Arab nationalism through major intellectual contributions in his highly influential La Nation Arabe periodical. In his own right, Arslan was formed by his youthful contacts with Mohammad Abduh and became a recognised spokesman for Sunni Islam as he produced treatises on the Islamic condition and biographies of Ahmad Shawqi and Rashid Rida. He was an ideal mentor in more ways than one for Missali.

Return to homeland

Missali turned away from communist ideology towards a more nationalist, even a separatist, outlook that displeased his former PCF friends. Not surprisingly, the French — including its nominal communist party adherents that pretended to place workers' interests everywhere above raw nationalist sentiments — put the interests of France and Frenchmen above the interests of Algeria and Algerians.

This fact left such an ingrained mark on unforgiving Algerians that, decades later few displayed any sympathy towards PCF members.

In the event, Missali was allowed by the Front Populaire to return home in 1936 for a short visit, to organise urban workers and rural farmers. Appalling conditions on the home front and the realisation that critical work was still needed in Paris, the intellectual revolutionary returned to Paris, where he founded the Parti du Peuple Algérien (PPA) in 1937.

He subsequently opened branches in Algeria and recruited new members, particularly in the Kabylie and Constantine regions and while French reports suggest that PPA members were few in number, Missali claimed to have over 11,000 supporters by October 1936.

Like many leaders of the Algerian revolution, Missali learnt the principles of the Great French Revolution in school, which ennobled the very concept of revolt in his mind. In the words of Alistair Horne, whose A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 stands as one of the finest books on the country, "at their best, the French schools provided an admirable breeding ground for revolutionary minds".

In 1944, Missali recognised that the French brought both enlightenment and repression and perceived the material benefits bestowed on Algerians. "The achievement of France is self-evident," he wrote, as "it leaps to the eyes and it would be unjust to deny it; but if the French have done a lot, they did it for themselves."

Missali wasted no time pushing his agenda for Algeria's independence from France. According to John Ruedy, whose book Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation is a key reference source on the nascent republic, "for the first time, the national [independence] question was raised on Algerian soil … [as] Missali began touring the country giving speeches, organising Étoile chapters and claiming that the Blum-Viollette Bill was no more than an attempt to co-opt the Algerian bourgeoisie while leaving six million peasants in ignorance and misery. He met with phenomenal success."

Tremors in Algerian politics

It must be emphasised that Missali's contributions to Algerian political affairs struck a severe blow to the Algerian Muslim Congress, which had combined two antithetical movements — one that aimed to accelerate the process of Algerian Gallicisation and another wanting to avoid it at all costs. Missali rejected the leadership of Mohammad Salah Bendjelloul from Constantine who was then the head of the Fédération des Élus Indigènes (1933 to 1936) and who led the grand coalition that became the Algerian Muslim Congress, because Étoile militants were kept off the board of directors.

Still, the Congress Charter demanded universal suffrage, representation in parliament, amnesty for political prisoners, separation of church and state, restoring confiscated property, removing restrictions on the use of Arabic, free education for all, improving public assistance and health, equal pay for equal work, aid to those in need without racial discrimination and abolishing the forest code that granted settlers financial privileges. At the time, the Leon Blum government in Paris saw it fit to grant citizenship to a minuscule number of Algerian évolués, though Missali fought for six million of his countrymen condemned to ignorance and misery.

When Missali objected to perpetuating the existing links between France and Algeria during the infamous 1936 Congress, he won the delegates' opprobrium. As it turned out, however, his pessimism was proven right, especially after the French defeat during the Second World War and the rise of the Fascist-leaning Vichy France. French settlers in North Africa ran amok with no restraints or fears.

With the 1942 landing of Allied troops in Algeria, a fresh environment emerged, as nationalist elements became emboldened. Likewise, and serving en masse on General Charles de Gaulle's Forces Françaises Libres (FFL), pressures for equality were bound to increase. The most vocal nationalist, Farhat Abbas (1899-1955), established close ties with the Americans. Needless to say, such ties created problems and as Missali was in prison until April 1943 and under house arrest until 1946, it fell on Abbas to assume the mantle of the revolution that finally issued the 1943 Manifesto to the Algerian People. Missali would not have objected to demands for self-determination, recognition of Arabic as Algeria's language, agrarian reforms and free compulsory education for both boys and girls, though he did voice displeasure with making these demands from the Free French Governor of Algeria, General Georges Catroux.

An overwhelmed Catroux jailed Abbas for being an agitator and, upon his release, by adding fuel to the fire through strict measures. French claims that Abbas's followers were tiny and that the vast majority of Algerians perceived themselves as forming part of the French nation belied the realities on the ground.

French settlers considered Abbas an American-backed radical, choosing to overlook indigenous views, most of which were inspired by Missali. Advising Abbas to insist on an independent Algeria, Missali acted as Abbas's backbone, especially when the latter came under immense pressures to make concessions.

By late 1943, De Gaulle promised educated Algerians the right of full citizenship, which he fulfilled in March 1944. Believing that this would appease nationalist fervour, De Gaulle stalled for time, though Abbas (against Missali's recommendations) created a new organisation that committed to Algerian independence through a federation with Paris. The Amis du Manifeste de la Liberté (AML) proved attractive but Missali, even under house arrest, remained unflinching. He wanted independence from France without any affiliations with it.

Lasting legacy

Though few remember Missali and his immense contributions to Algeria's independence, many know of the May 1945 Sétif protests, following extremely poor harvest. Demonstrations near Constantine, ostensibly to celebrate victory in Europe, led to a systematic suppression of the AML and Algerians in general. In Sétif, thousands carried placards calling for Missali's release and Muslim-Christian equality. Many also bore the 19th century green-and-white banner (the colours of the Algerian flag) of Amir Abdul Qader.

When shots were fired and widespread rioting ensued, hundreds were killed, which set the stage for massive resistance. Over a short period of time, thousands were gunned down throughout the vast country, even if many Algerians bled for French victory in Europe. The AML was banned, leaders were executed and many ordinary citizens were imprisoned. Though Missali and others were overtaken by events, as younger revolutionary leaders fought tooth and nail until ultimate freedom, most drew succour from the vision of the one who dreamt of freedom.

Life of a rebel

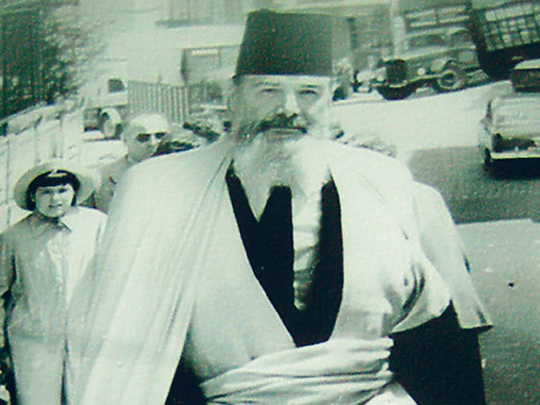

Al Hajj Ahmad Missali (also spelt Messali Hadj and Messali Al Hadj) was born in Algeria around 1898 and became one of that country's greatest nationalist politicians. A central figure in the nationalist build-up towards the Algerian War (1954-1962), he devoted most of his life to establishing the foundations of freedom, even if his influence over the development leading to independence and the founding of new political and state structures in 1962 were taken for granted. His politics were moderate and pragmatic, yet founded on Marxist principles. Elected chairman of the Algerian workers' association in Paris in 1927, Missali advocated complete independence for Algeria, where he returned in 1930 to establish the Étoile Nord-Africaine (North African Star). Arrested several times by French authorities after his party was outlawed, the French educated Missali, who

joined the French army for three years in Bordeaux and married a French woman.

In 1937, he helped create the Algerian People's Party (PPA) but was arrested in November that year for agitating. Following a trial, he was imprisoned, which allowed him to reflect and plot. When he was freed from prison in 1946, together with Farhat Abbas, a fellow nationalist companion, he formed the democratic group Mouvement pour le Triomphe des Libertés Démocratiques (Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties or MTLD), which was replaced by the Mouvement National Algérien (MNA) in 1954, an organisation that stood as a competitor to the Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front or FLN).

The MNA's guerilla wing was destroyed by the Armée de Libération Nationale (National Liberation or ALN) and when talks were held between the FLN and the French government in 1961, the MNA was not included. After Algeria gained its independence in 1962, Missali tried to reshape the MNA into a political party but to no avail. Dejected, the former member of the Communist Party of France spent the last years of his life in France writing his memoirs and died in that country in 1974.

Dr Joseph A. Kéchichian is an author, most recently of Faysal: Saudi Arabia's King for All Seasons (2008).

Published on the third Friday of each month, this article is part of a series on Arab leaders who greatly influenced political affairs in the Middle East.