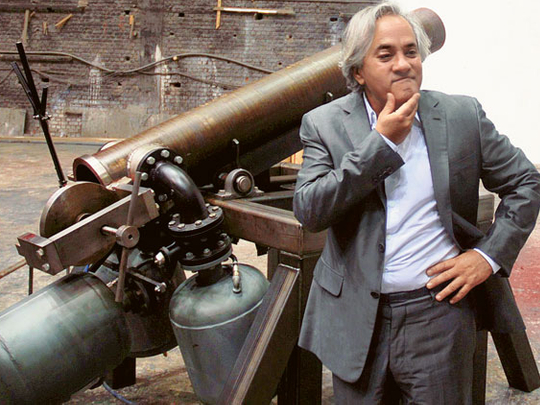

It is a hot, humid evening and Anish Kapoor is addressing a glamorous crowd at the opening of his new exhibition at Mehboob Film Studios in Mumbai. "When I was growing up here in Bombay," says the Turner Prize-winning sculptor, "it was a fantasy of all my friends to become a Bollywood star. For me, in a sense, that fantasy has come true." He is speaking metaphorically, referring to his show. Inside one of Mehboob's sound stages, Kapoor, in collaboration with the British Council, has placed six enormous mirrored works, with two pieces that involve masses of dark crimson wax, including Shooting into the Corner, a cannon that periodically fires giant globs of viscous red matter on to the walls.

The space's stripped-back brickwork offsets the flawless finish of the sculptures, which distort the reflections of passers-by like those reality-bending mirrors that grace travelling fairgrounds. The mirrored works are both beautiful and terrifying, threatening to rupture the space-time continuum, and transport you to a different dimension — or oblivion.

Related works by Kapoor can be seen in London's Kensington Gardens, where the Serpentine Gallery has installed them until next spring. The Mumbai show is one of two Anish Kapoor exhibitions in the subcontinent. In Delhi, a ravishing retrospective of Kapoor's art, including examples of the pigment pieces that made his name in the early Eighties, along with architectural models for his public projects, is opening in the National Gallery of Modern Art.

Outside the entrance, one of Kapoor's circular Sky Mirrors reflects the hazy heavens, like a satellite dish tuned into the divine. Such is the prestige that Kapoor enjoys in India that the celebrated Indian politician Sonia Gandhi presided over the private view in Delhi. Yet these exhibitions are the first time this "son of India" has shown work in his homeland. Why has it taken him so long? "Because it's complicated," Kapoor says. "The British Council, the Indian government and I have been talking for at least ten years, probably longer. Sculpture is difficult to move, it's expensive to move, the space wasn't right, etc."

No doubt the practicalities required to stage two such ambitious shows are tedious and tough to overcome. But I also wonder whether the delay might have something to do with Kapoor's reluctance to be labelled as an "Indian" artist. Kapoor was educated at the independent Doon School — often described as the "Eton of India" — but he ended up studying art in London in the Seventies and has lived and worked there ever since. "I still am reluctant," he tells me. "I grew up here, so of course India is one of the contexts for me. But I want the work to be looked at for what it is and not for the fact that I'm Indian. Think of any artist: You don't refer to Picasso in terms of his Spanishness, because it attributes too much of the creative energy to a background culture."

Seeing Kapoor's work in India inevitably shifts the emphasis back to his roots. For example, the early pigment works — structures that look as if they have been shaped out of piles of brightly coloured powder — are redolent of the intensely chromatic cones of spices commonly found in Indian markets or the unusual architecture of the 18th-century Jantar Mantar astronomical observatory in New Delhi. Significantly, Kapoor started to make his pigment pieces shortly after visiting India again in 1979. "One of the contexts may be Indian," Kapoor tells me. "But then again, there is a great tradition of monochrome painting from the Fifties onwards: Yves Klein, Barnett Newman and many other Europeans and Americans." He pauses and the high-pitched horns of Delhi's auto-rickshaws make themselves heard. "Of course, this is a homecoming," he says. "I have always carried a vision of India somewhere in my soul. So to bring the works back to an Indian context is a curious thing, because in a way they have to stand up to what's out there — and what's out there is pretty complex. India is profoundly mysterious."

One of the most noticeable aspects of Kapoor's work is his obsession with voids and negative spaces. For instance, Untitled (1992), a four-tonne block of rough-hewn sandstone, has been hollowed out to reveal an oblong void stained with an indigo pigment so dark it seems to exert a gravitational pull on the space around it, like a black hole. In the past, Kapoor has spoken of the impact of the Elephanta caves to the east of Mumbai on his art. Is the void an expression of the mystery that he talks about at India's heart? "It probably is," he says, somewhat abruptly, suddenly uncomfortable talking about such personal matters. Does he think India is finally claiming him as one of her own? "Seems to be," he says, with a tight smile. "And I am."