The sound system was on the fritz in Russian technology billionaire Yuri Milner’s $100-million (Dh367.2 million), 30,000-square-foot mansion in Silicon Valley.

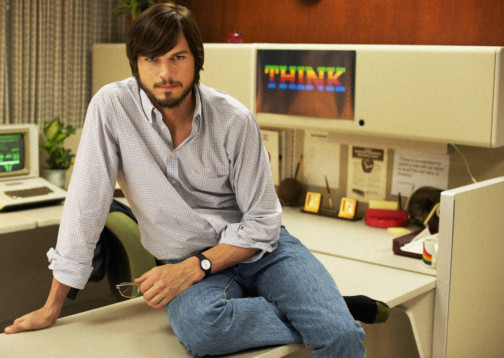

Cocktails and hors d’oeuvres had been served. The guests had taken their seats in Milner’s home theatre. And Ashton Kutcher was ready to screen Jobs, the new film in which he plays the late chief executive and co-founder of Apple. The audience was a who’s who of the technology industry, including venture capitalists John Doerr and Vinod Khosla.

Tesla and SpaceX founder Elon Musk was the one who rolled up his sleeves and fixed the audio. On the screen, Kutcher appeared as a young Jobs in the early and troubled years of his journey from his LSD-laced days at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, to the formation of Apple, his ouster and victorious return.

“I can’t think of a more skeptical audience than Silicon Valley when it comes to a movie about Steve Jobs,” said Nirav Tolia, chief executive of the social network Nextdoor.

Film industry observers were skeptical too. Vanity Fair’s post announcing Kutcher’s role was titled “How to Handle the News of Ashton Kutcher Being Cast as Steve Jobs Without Giving Up on Hollywood.”

But when the lights came up at Milner’s house, Kutcher found himself before an appreciative audience. At one point, as he and costar Josh Gad took questions, Kutcher choked up as he spoke about how deeply personal the role was for him.

“Of all people,” Tolia said, “Ashton could do it because he is one of us.”

The Hollywood heartthrob not only plays a dotcom billionaire on CBS’ Two and a Half Men but he is also co-founder with Madonna manager Guy Oseary and supermarket magnate Ron Burkle of the venture capital fund A-Grade Investments.

In taking on the role of Jobs, Kutcher didn’t have to “learn how to channel being an entrepreneur,” said Tolia, whose Nextdoor network is one of A-Grade’s investments. “Acting is his vocation. Technology is his avocation.”

“The role was the perfect convergence of my craft and my interests,” Kutcher said.

As soon as he heard about the part – even before he met with director Joshua Michael Stern – Kutcher started preparing to play Jobs.

“When I read the script, the idea of someone playing him who maybe didn’t care made me just want to jump at the role,” Kutcher said. “I knew it was going to take a while to figure out who this guy was, where he was coming from, what made him tick. I figured if I started studying who he was, the worst thing that could happen is that I would learn a lot about Steve Jobs.”

By the time Stern walked into Kutcher’s Los Angeles home for their first meeting, the actor had already begun to subtly master Jobs’ speech patterns and hand gestures, even the slope of his back and the way he walked by bouncing on his toes.

“Without being showy,” said Stern, who directed Neverwas and Swing Vote, “he was becoming the man.”

Stern hopes Kutcher’s star power will help the independent Jobs stand out among summer blockbusters when it opens on Friday – and in comparison to Aaron Sorkin’s still-uncast big-budget adaptation for Sony of Walter Isaacson’s biography Steve Jobs.

Kutcher, who bears an uncanny resemblance to a young Jobs, says he was determined to understand Jobs’ flashes of genius and his stubborn, uncompromising nature.

“I have a lot of friends and colleagues in the tech space and a lot who knew Steve,” Kutcher said. “I wanted them to feel like what was being represented was true to them.”

Three months of exhaustive research helped Kutcher get inside the head of a man he never met. Or it could be that Jobs got inside his.

At a recent screening in San Francisco, Kutcher passionately defended Jobs’ controversial decision not to give stock options to some of the earliest Apple employees who had not lived up to his expectations.

“I think Steve was extraordinarily loyal to people he felt were loyal to him,” said Kutcher, who called Jobs this generation’s Leonardo da Vinci.

Though the film received tepid reviews after premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in January and has been criticised for giving too much credit to Jobs for Steve Wozniak’s vision for the personal computer, Kutcher has been praised for moments in which he seemed to embody Jobs – staring himself down in the mirror after denying paternity of his child or standing triumphantly on the floor of the West Coast Computer Faire with Wozniak to unveil the Apple II.

Even when he’s showing Jobs at his most callous, Kutcher humanises the man who died from complications of pancreatic cancer in 2011. “There were these inconsistencies in his behaviour,” Kutcher said. “I wanted to figure out why he made these choices. Why this brilliant man did not seek medical treatment for something he knew would be fatal. Why this guy who was so brilliant would use such brute verbal force to make changes.”

He immersed himself in Jobs’ spiritual beliefs with Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi and Ram Dass’ Be Here Now and in his musical influences by listening to Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. He studied Thomas Edison and Ansel Adams.

For scenes set in the garage of Jobs’ childhood home in Los Altos, California, Kutcher read up on integrated circuit design. When driving in his car and as he fell asleep at night, Kutcher played some 100 hours of every Jobs interview and speech he could find. That attention to detail extended to Kutcher’s physical appearance in the film. Skeletally thin, the actor landed in the hospital for two days after losing 20 pounds on the fruitarian diet Jobs followed.

But Kutcher gained the most insight into Jobs by meeting some of the people who knew him best.

“I got to meet Avie Tevanian,” Kutcher said with a tone of awe about the former Apple software wizard. “That’s sick.”

Kutcher also met computing pioneer Alan Kay of Xerox PARC fame.

“I gave Ashton a picture of the real Steve from the point of view of someone who knew him for many years, who talked with him every few months on the phone,” Kay said. “Steve was not an idol or a myth or a god.”

Kutcher said Kay recalled the anguish Jobs felt over sharp criticism of the Macintosh. “Alan said to him, ‘Steve, the only reason they are criticising the Macintosh is that you built a personal computer that is good enough for people to criticise,’” Kutcher said. “Since Steve was adopted, he felt like he was rejected by his birth parents. He filled that hole by building beautiful things people would appreciate. When they rejected the products, they were rejecting him.”

Gad, who plays Wozniak, said he’ll never forget the first time he talked to Kutcher over Skype and encountered his encyclopedic Jobs knowledge.

“He knew everything not only about Jobs but could literally rattle off the tiniest detail about Steve Wozniak as well,” Gad said. “I hung up with him and ordered every piece of literature and watched every single video I could like a student who has to cram for the SATs the night before the exam.”

One day, Kutcher walked onto the set and squinted at a circuit board in the back of the room.

“’This wouldn’t be invented for two more years,’” Gad recalled Kutcher saying. “That attention to the tiniest detail informed the entire shoot.”

Technology has always held a fascination for Kutcher, who was raised on an Iowa farm. In college, while studying biochemical engineering, he started programming. He took a detour into modelling and acting after being spotted by a talent scout and dropping out of college at age 19.

An early adopter of technology, Kutcher even sported a Motorola two-way pager back in the day. Soon he was experimenting with the Internet. In 2000, he spent hours in AOL chat rooms to get people talking about his film Dude, Where’s My Car?

Kutcher was intrigued by the possibility of Internet video long before streaming was possible, and his production company explored creating video for the instant messenger program AIM. The prescient idea that people would want to share snippets of video with their friends was close to what people now do every day on Facebook and Twitter.

Kutcher’s first tech forays, the Internet calling service Ooma (which now has a new management team) and the animated Web comedy series Blah Girls, lost money. But he embraced Twitter long before it was cool, becoming the first to reach 1 million followers on the service. And he started investing in up-and-coming consumer Internet companies – question-and-answer service Quora, music streaming service Spotify, car service Uber.

Kutcher’s growing business savvy impressed prominent investor Marc Andreessen, who said he helped Kutcher invest in Skype, which later sold for $8.5 billion.

Elliot Cohen, founder and chief executive of CityMaps.com, says Kutcher is more hands on than most investors. He gets emails at all hours from Kutcher about ways to improve its social mapping product.

“He always knows exactly where we are in our build cycle,” Cohen said.

“Steve Jobs is an incredible case study for building a great business. He made mistakes, but he did an extraordinary amount of things right,” Kutcher said. “I try to look at those ideals he had that were extremely positive: simplicity, innovation, focus and brutal honesty, and I try to encourage entrepreneurs around those ideals.”

Kutcher now is on the lookout for the next Steve Jobs and just hopes he’s smart enough to bankroll him or her.

*Jobs releases in the UAE on August 22.