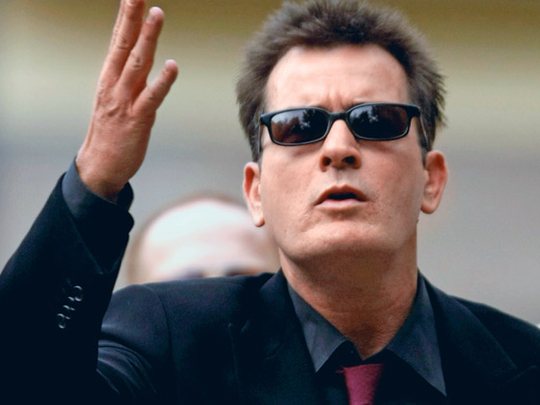

It’s 10 minutes before show time backstage at NBC Studios in New York, and Charlie Sheen is revving up to go on Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night show. He hops about in his dressing room, fixing his hair and smoking, until a woman with a clipboard apologetically informs him the fire alarms are about to go off. Sheen politely puts it out. “I can see the approach,” he says, “the shift, the evolution, from pupa to chrysalis. The perception people have of me is always shattered when I meet them.”

It’s a reputation that doesn’t so much precede as eclipse him. The 47-year-old, who is appearing on the show tonight to publicise his sitcom Anger Management, is not the Sheen we knew five years ago. Before his extraordinary meltdown in 2011, he was the highest-paid actor on US television, a veteran movie star and the scion of an acting dynasty. Now, as he acknowledges with many wry asides that make it impossible not to warm to him, he is a curiosity. “Ninety per cent of what I say is horses***,” he says after the show, taking a bottle of beer from the dressing room minibar.

“Ten per cent is gold. And you never know when it’s coming, so you have to pay attention.” It is the kind of aphorism that, even when he was at his most manic, distinguished Sheen from other Hollywood stars having public breakdowns fuelled by drugs and alcohol.

He is slight, frowning, thoughtful; gloomy about himself, with sudden up rushes of delight. He talks through his nose, in rapid jags that sound like the side-effect of whatever he has done to his brain over the years cocaine mostly and that made his stage show, Violent Torpedo Of Truth, one of the oddest spectacles I have ever seen. Sheen embarked on the stand-up comedy tour in 2011 in the wake of being fired from Two And A Half Men, when his stream of consciousness was broadcast across all available media. He was half-mad, raving at his former boss, Chuck Lorre, and slating him for under-appreciating his star. The show I saw at New York’s Radio City was hideous, like something at the Colosseum under Nero, in which Sheen, fitfully eloquent and vulnerable on stage without much of a script, was confronted by a drunk male audience that halfway through the show turned on him with a chorus of, “You suck!”

“Awful, awful,” he says, leaning forward and back in his seat like a metronome. “The Friday or the Sunday?”

The Friday.

“That was a bomb. Sunday I came out and killed it. Friday we ate s***. It was a mess. I don’t know how I survived that thing. I don’t know how I didn’t throw in the towel up in Detroit. It was a disaster. Everybody was calling from venues to cancel all the other shows, there were lawsuits. Just s*** city, you know?”

He did it for the cash because at the time, he says, he was broke after going on a spending spree with his earnings from the sitcom. “I was spending it like a drunken sailor and having a ball. I’d never made that kind of money before.” He was also giving it away, with the largesse of the barfly see his bailout of Lindsay Lohan’s tax bill. Whatever people say about Sheen, they don’t accuse him of parsimony, not even his ex-wives. (A production assistant on the show who flew in with Sheen from LA told me there was no reason for him to be there, but the actor, knowing his mother lived in New York, put him on the passenger list.) “I love making money and I love spending it,” Sheen says. “I spend more on others than on myself. Part of my code is, when I eat steak, everyone eats steak. Vegans be damned.”

It is a grandiloquence that in different circumstances gets him into trouble. In an interview in the New York Times last year, the actor made appropriately apologetic overtures to Lorre, the co-creator of Two And A Half Men, and resolved to send him a note saying, “Hey, man, no hard feelings”, but he is almost incapable of biting his tongue. It’s bizarre, a form of self-detonation that makes one wince but that one can’t look away from. It has moments, too, of spectacular, self-lacerating honesty.

“They kept all the money,” he says, looking rueful at what he is about to do. Who? “Warner Brothers,” he says, and he’s off: his sense of injustice at the way the pie of Two And A Half Men was divided; how, although he was paid a reported $1.8m an episode, he had no equity in the show and forfeited the lion’s share. (He has not made the same mistake with Anger Management, in which he owns a large stake.) How they gypped him, he says, out of all sorts of other revenue.

“You gotta think about the shows that my show launched. I should have added in a clause that said anything that uses me as a lead-in, cut me in. [Big Bang Theory was scheduled to run after Anger Management, so piggybacking on his audience, according to Sheen.] I’m sorry, but Big Bang Theory is a piece of s*** it’s a stupid show and it’s just lame, about lame people. I like the kids in it, but that show without us as a lead-in is goodbye. And I’m rooting for those kids, because I know who they’re dealing with. The fact that they’re still sane is crazy. You know? He’s a bad man. And I’ve backed off from him for a while.”

Who?

“Chuck Lorre.”

Oh God.

“Look what happened to Angus [T Jones], man. Look what happened to me, look what happened to Melanie Lynskey, who’s getting divorced. That show devoured like 12 marriages.”

First time around, insulting Lorre was amusing theatrical schtick, but then Sheen made the weird call to “insult” him by using a Hebrew version of his name, Chaim Levine, and it all threatened to go a bit Mel Gibson. It sounded anti-semitic. No, no, no, Sheen says. “My mum’s Jewish. I’m Jewish. I just think he’s a fraud and phoney and a fake.”

But your own name has been changed! (Sheen was born Carlos Estvez.) “Yeah, but I admit it. My buddies call me Carlos.”

Was his mother displeased? “No. She was like, ‘Go at him harder.’ I can’t talk about this man without getting mad.”

Sheen’s mother, Janet, is one half of that rarest of Hollywood sightings, the lifelong marriage. She and Martin Sheen have been married since 1961 and, besides Charlie, produced three children: Emilio, Ramon and Rene. The latter two work on Anger Management; in fact, Ramon, the show’s producer, is floating around the corridor outside wearing a waterproof jacket and a mild expression. He is the spitting image of their father much more so than Charlie. Their sister, Rene, is a writer on the show; their father made an appearance in the first season; and Taylor, Sheen’s nephew, is his personal assistant. “Get my mum and Emilio on, and we’re done,” he says.

Anger Management is a conventional sitcom with a loud laughter track and ba-ba-boom jokes, which has already exceeded its ratings projections. Sheen plays a group therapist struggling with his own anger issues, father of a teenage daughter and romantically involved with a fellow therapist played by Selma Blair. Watching it, one is reminded of how likable an actor Sheen was before his public persona took over. He is warm, funny and deft in the role, with flashes of the seriousness one remembers from his heyday in Wall Street and Platoon. His acting mentors were Edward Platt, from a sitcom called Get Smart, John Amos, Leslie Nielsen and George Carlin. His comedy style is very Nielsenesque, with similar reliance on the double take and that same pantomime incredulity. And he’s a pro. There is nothing Sheen likes more, he says, than to be “the guy they go to at the end of the night when everyone’s really exhausted, with a scene that’s really challenging. Not to boast, or show off, but that’s when people see why I’m still doing this at the level I’m doing it at, and why people keep tuning in.”

It’s true. It’s also true that almost anything is forgiven when the money keeps rolling in. Sheen’s talent enables and excuses his bad behaviour. If you weren’t talented, I suggest, you’d just be a jerk, which he takes as a rebuke to his self-congratulation. He’s not being arrogant, he says. He’s half poking fun at himself, in the same way that he insists his tattoos are not tattoos but satirical comment on tattoos. “It’s grandiose. It’s grandiose in a fun way.”

Sheen could be making more money than he is. He has 8.8 million Twitter followers but doesn’t accept sponsors for the feed. “I don’t want people signing me up to help them sell a bar of soap, or shoes. When you have a day job that pays like mine, don’t shake the tree any harder you’re going to break it. How much do you need?”

I wondered whether he had trouble getting insurance to make the new show, given his shenanigans, but he says no. Sheen has joked that his dad is involved just to keep an eye on him, but actually he never was in the Lindsay Lohan category of investment-risk. “I was a ball player before I was an actor. And I’m a huge fan of team discipline. If I prepare, it makes everyone else’s job easier. I mean, I’ll roll in sideways some of the time, but I’ve got enough in the vault to draw on to make it work regardless of how I’m feeling.”

He is so adept at rationalising his behaviour that I wonder if he even considers himself to have had a breakdown. He sort of does and sort of doesn’t. Herefers to it, with Sheenian evasiveness, as “not a meltdown but a melt forward. I don’t know what happened, man. It wasn’t just the show. It was 30 years. Gaaaaaaah. I didn’t know what to do. I wanted to swallow my own teeth.”

He says: “I was kind of adrift at sea. I didn’t have any charts or GPS. No nav system.”

Sheen has a group of friends with whom he goes back to childhood. He was at school with Rob Lowe and Sean Penn, and was good friends with Sean’s brother, Chris, who died in 2006. He calls them “reliable as the sun” and says, “It’s as much about the group as it is about the man. It’s never an effort to maintain a great friendship. It’s a code. People have lost the code. It’s really sad. There’s two things missing from society right now common courtesy and common sense.”

The question is whether these guys were able to talk to him at all during his maniacal period, when he was phoning in to radio shows raving about tiger blood and his Adonis DNA. As the world watched, and bafflement grew into unease, spectators turned to each other and said vaguely, “Er, is somebody going to do something?”

Did he listen to his friends at that time?

“Hell, yeah.”

But if they said to him, “You’re not making sense, you’re talking s***”, was he able to hear it? There’s a pause. “To a degree. But that wasn’t really supporting or in the essence of our uprising. Those voices were cast out or asked to be quiet and not attend the party.”

A lot of people felt sorry for Sheen’s dad, who commented at the time, “The disease of addiction is a form of cancer. You have to have an equal measure of concern and love, and lift them up, so that’s what we do for him.” I suspect that growing up as Martin Sheen’s son was less cosy than fans of The West Wing imagine. At 11, Charlie was on location in the Philippines while his dad filmed Apocalypse Now. Emilio said in a recent interview that their father was drinking heavily at the time and was occasionally violent. He paints a picture in which the two boys were woefully underparented.

Martin Sheen has been sober for 20 years now, but having him as a father was “intimidating”, his youngest son says not least because of his fame, which was like “a giant fear that was present. It was a tremendous a constellation of all things awe-inspiring. And for a child, that’s a lot.”

In 1998, Sheen was hospitalised after a cocaine overdose. That year his father turned him in for violating his parole and asked his fans to pray for him. What did Sheen Sr say to his son this time when he went off the rails?

“He said, ‘OK, you did all that. Now go get your money and take care of your kids.’ Go take your money back. That’s what he said. He’s not a capitalist! He doesn’t care about anything financial or commerce-wise. He’s just the best guy alive. He gave me a mission. Go get your dough and take care of your kids. I had purpose again.”

It sounds more of an admonishment than Sheen is willing to admit. Looking after his kids requires some diplomacy these days, given the unhappy history he has with their mothers. Sheen’s relationships include a litany of calls to the police and domestic violence charges. In 2009, he was charged with assault and criminal mischief in regards to his then wife, Brooke Mueller. In 2010, he was ejected from the Plaza hotel in New York after allegedly causing thousands of dollars’ worth of damage and leaving a porn star cowering in the bathroom. He has five children: the oldest, 28, is about to make him a grandfather, while the youngest are three-year-old twin sons by his third wife, Mueller. Then there are two daughters by Denise Richards, his second wife. As a dad, he says, “I’m just a goofball. I’m flawed, I’m funny. Iuse all the wrong language. But the kids are never in danger. When it comes to, like, linear awareness of where the kids are, coming up on the counter, watching the step, keeping them all safe, I’m like super-worry dad. You have to be, man.”

Where are they now? “Um. The girls are with Denise right now and the boys are with Brooke. And nannies. I bought them all houses in the neighbourhood; I bought Denise a house, for the girls’ trust. And I bought the boys a house, for their trust. They can live there with their mums, and it’s a pretty easy scenario for me. My kids love me to death. I don’t even care what the exes think of me any more, I really don’t. I’ve done everything I can. I gave them the world and I still get b****** at for nit-picky s***. Whatever.”

What’s it like to be married to you? “Tons of [expletive] fun if you just relax and quit b******* at me every day. I don’t believe in panic, excuses or failure, you know?”

Are you violent?

“No. No, I’m passionate. Extremely passionate. When pushed, we have to defend ourselves and our honour or something. There’s some s*** I wish I could take back. But this whole undercurrent of domestic violence is just bull****. It’s not true at all.”

Did you hit your wives? “No. I yelled. No. No.”

Later, on the phone, I ask what he’d take back and he says whimsically, “Tattoos and smoking.”

I ask what makes him angry and he says, “People that talk too loud and people who interrupt. Such an issue. The things I’ve done to my brain People need to realise that when I’m making a point, I’m on a trail to get me there and do not throw s*** in my way, because it’s questionable whether I’m going to get there without interruption.”

Contrary to advice about how to manage addiction, Sheen is not teetotal. He tried for 11 years and then decided it wasn’t for him. He is caustic about AA. “I thought, I’m taking the advice of who? A bunch of former homeless douchebags? I got a problem with AA, man. It was written by hard drunks 100 years ago, and a lot of it doesn’t apply to today’s standards and realities. They’re like, ‘Oh, but the language is so important.’ Oh, shut up.”

After the interview, Sheen is due to go to a bar downtown, and two tall, slim, ritzily dressed young women arrive to accompany him. “Charlie’s friends,” a Sheen representative says, looking weak. A couple of days later, when we speak on the phone, he says he didn’t even get out of the car. The place was too crowded. “I didn’t feel like signing and hugging the whole bar, you know?”

He sounds weary. Anger Management is on hiatus at the moment and he is spending the week doing voiceovers, seeing his kids and hanging out at home. “You know, life,” he says. “The moments between the moments, where life happens.” With what sounds like an almost physical effort, he cranks up his enthusiasm. “It’s never dull. It’s always fun. I’m having a ball, man. People don’t realise, they think it’s this big struggle. Bull****. It’s a ton of fun.” Quietly he says, “This is a dream life.”

Anger Management season two is on Comedy Central on Wednesdays at 10pm.