The seat belt of the four-door pickup cuts into my shoulder as I bounce down a rutted path through a buzzing, sticky swathe of Yucatan jungle. With the truck bed full of air tanks and scuba gear, I’m rolling shoulder to shoulder with Nat Wilson, an Arizona-born cave diver who moved to the Riviera Maya to feed his addiction for underwater exploration in the world’s largest underground river systems.

As we drive, he’s holding court on the mythology behind the freshwater-filled caverns that perforate this landscape. “The ancient Maya believed the openings served as portals to Xibalba, the Mayan underworld,” he says, before slamming on the brakes and swerving to the shoulder. “You see that?” he interjects, his index finger pointing out the side window. “Through this hole in the trees, see its tail?” I look harder; fairly impressed that he could spot anything through the dense underbrush, let alone from a moving vehicle. And then I see it, a small blue bird with a scissor-like tail.

“That’s the motmot,” Wilson exclaims. And without missing a beat, he launches back into his previous story, adding that the Mayans considered motmots to be the guardians of the cenotes. “In reality, they hang around the caverns because it’s the only access to fresh water out here,” Wilson says. And these days we cave divers watch for the birds to find the entrances.

Of course, as a long-time guide to scuba diving in these caverns, Wilson doesn’t need a motmot to help him find where we are headed today. Of the dozens of cenotes open to divers, snorkellers and swimmers, Dos Ojos (Two Eyes) is one of the most popular; increasingly subjected to throngs of visitors who splash around the mouths of its two caverns, or ‘eyes’. But Wilson assures me that deep underground, its popularity is well deserved.

In order to get underwater before the tour buses and dive groups from Playa del Carmen can crowd us out, we park at the trailhead early in the morning, quickly strap on our scuba gear, and make our way on foot down the trail to the east eye.

I notice smoke billowing up from brush fires around the opening, and when I ask, Wilson explains that the locals, modern-day Maya who own the land around the cenote, build the fires as offerings to the gods. “Really?” I ask hesitantly.

“No, not really,” he laughs. “They are for the bugs.” I slap a handful of mosquitoes slurping from my ankle. “It’s a good story,” I counter. “You should’ve stuck with it.”

Despite the bonfires, the mosquitoes are drinking their fill from our exposed feet and hands so we make quick work of a backflop from the slab of limestone that overlooks the gin-clear water, do one final gear check and slip underwater. Dropping slowly to the floor of the pool, we fin to the tied-off guidelines that stretch into the shadowy mouth of the cavern.

To the right, the Barbie Line follows an easy, well-lit path that explores the entrance of the west eye. To the left, the Bat Cave Line extends 25 metres into the opening of the submerged cavern before hanging a sharp left into a darkened side passage. We take the latter.

Wilson assumes the lead, hovering skilfully half a metre above the thin rope to avoid stirring up the fine sediment on the cavern floor, a move that would cut our visibility to nothing. I kick gently to keep pace as we slip into the dark passageway, torch beams bouncing off stark, white limestone formations, thick floor-to-ceiling columns and hanging stalactites that formed eons ago before these tunnels filled with water.

After swimming for a few minutes, we make another left turn into a large chamber, where a narrow beam of light coming through a small hole in the distance provides dim illumination while we follow the contours of the wall, dipping and weaving past tumbled boulders and towering rock formations. Eventually, the guideline slopes upwards, leading us into the cave’s eponymous feature.

Once we fin into the Bat Cave, we swim slowly for the surface, watching it ripple with the agitation of our rising bubbles. And as our heads break through the water, the vast, circular cavern expands into a dry chamber tinged green by sunlight from a small opening in the roof. Popping up into the air pocket, I remove my regulator and take a breath of the cool, damp air.

True to its name, the ceiling of the cavern boasts clusters of small bats; occasionally one swan dives from its upside-down perch and glides over the electric green pool only to arc upwards and alight once again on the moss-covered ceiling.

All too soon, it’s now time to turn back from this secret grotto beneath the Mexican jungle. Dropping again below the surface, we take one last underwater tour of the chamber, circumnavigating a jumbled pile of rock slabs that had fallen from the ceiling to create a mesa-like mound in the centre of the room.

Along the edges, we squeeze through a fissure beneath the limestone walls, and meandering through the tight maze of stalactites and stalagmites, we pass underneath some of the most delicate formations I’ve seen in any dive through these cenotes. Huge swaths of the ceiling bristle with soda-straw stalactites, pencil-thin protrusions that blanket the surface en-masse like beds of nails.

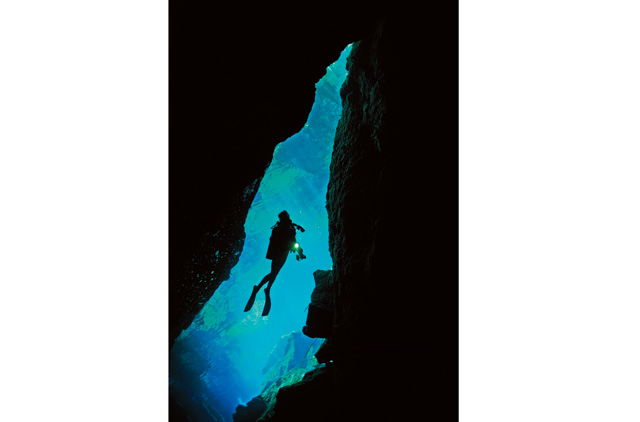

Eventually we reconnect with our guideline and follow it back along the edge of the west eye. Moving slowly, we cover the beams of our torches by holding them to our wet-suited chests. From this vantage point, the sunlight filtering through the main entrance puts the whole cavern in silhouette, and laser beams of light filter past the edges of the pillars and formations that line the mouth of the cavern like a jumbled collection of craggy teeth.

Just like that, it’s over. We scale the limestone slab at the edge of the pool by way of a rusty swim ladder, and Wilson matter-of-factly starts back up the trail. But I hesitate for a moment, looking back over my shoulder. And just as I’m about to turn and leave, I spot it again from the corner of my eye. A small blue bird, tail bouncing disjointedly, perched on the lip of the cavern as if overseeing our departure.