When Ann Wiltshire read that Hollywood actress Angelina Jolie had undergone a double mastectomy at the age of 37 after discovering she carried the faulty BRCA1 gene – which significantly raises the risk of breast and ovarian cancer – she knew exactly how she felt.

For Ann, 52, had made the same decision after watching her sister Lyn Howlett battle ovarian cancer, and being diagnosed with the faulty gene just six months later. “It was a no-brainer,” says Ann. “I would lie awake in bed worrying. I had many sleepless nights, and it was affecting my life because I was terrified that I too would develop cancer.”

Her grandmother had died of ovarian cancer and she’d supported her sister through surgery to remove a cancerous tumour and while she started a drugs trial to keep the disease in check.

So, like Angelina, Ann chose a courageous route, with the support of her husband Roger. Rather than undergo annual checks aimed at detecting early signs of the disease, she had a hysterectomy last October and a double mastectomy with immediate reconstruction in April this year.

Having now recovered from the eight-hour gruelling surgery, she has no regrets. “My lifetime risk of breast cancer has now fallen from 80 per cent to just two per cent, which is wonderful,” she says.

What’s in a gene?

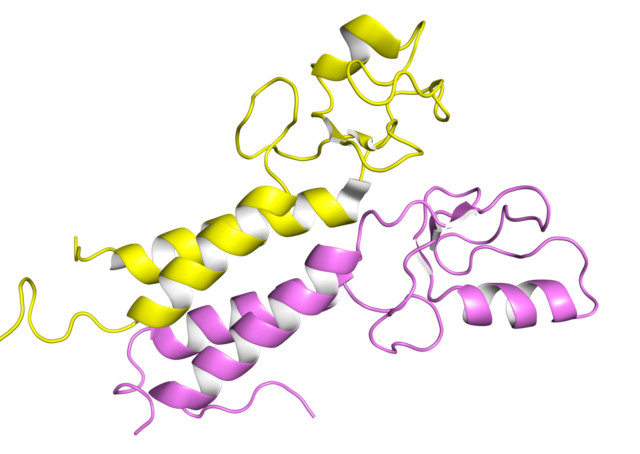

BRCA1 and BRCA2 belong to a class of human genes known as tumour suppressors, according to the National Cancer Institute. In normal cells, BRCA1 and BRCA2 help ensure the stability of the cells’ genetic material (DNA) and help prevent uncontrolled cell growth. However, mutation of these genes has been linked to the development of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and women who carry a faulty copy of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are at much higher risk of developing both.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, according to the World Health Organisation, and in the UAE it makes up around 23 per cent of cancers in females. Around five per cent of women with breast cancer have a mutated BRCA gene. The gene vastly increased their lifetime risk of developing cancer to between 50 and 80 per cent by the age of 80 – they are also at increased risk of getting the disease early in life. And while around 1.7 per cent of women get ovarian cancer, among women who carry a BRCA mutation the risk can be as high as 60 per cent. Yet even women with relatives who have had breast or ovarian cancer should not worry unduly about the possibility of them carrying the faulty gene, say experts.

“Breast cancer is a relatively common cancer, and around eight per cent of women will develop breast cancer some time,” says Dr Sanjida Ahmed, research director of Eastern Biotech & Life Sciences in Dubai, which introduced the BRCA test to the UAE in 2009. “An inherited predisposition to develop breast cancer because of an alteration in a BRCA gene is uncommon, occurring in about one in 20 cases of breast cancer.”

At the Well Woman Clinic in Dubai, consultant breast surgeon Dr Houriya Kazim agrees. “Less than 10 per cent of cases are due to a genetic mutation. Some women perceive themselves as having high risk because their grandmother had breast cancer at the age of 60 or 70. Medically, this would not be considered high risk and we would not advise these women to have a genetic test.”

The pros and cons of testing

“I tell women only to proceed to testing if they are willing to act on the results – the woman should be prepared to remove both breasts and perhaps both ovaries should she test positive,” says Dr Kazim. “If she is not ready psychologically, then I would not do the test – it would give you a lot of anxiety if you test positive.”

Options other than risk-reducing surgery include close surveillance with annual mammograms and MRI scans, lifestyle changes such as losing weight or stopping smoking, or selective anti-hormone drugs to reduce risk, says Dr Kazim.

However, women who test positive and do not go on to have risk-reducing surgery can be refused health and life insurance cover, she points out. Those who do opt for testing are also advised to have genetic counselling, as the whole experience can be traumatic. This involves a personalised risk assessment before the test, taking into account your family history and medical background, and psychosocial support, follow-up and guidance throughout the proceedings and afterwards.

Angelina Jolie’s decision to have a double mastectomy was brave, says Dr Kazim. “It is never an easy decision to make, even if you know you are carrying the mutation. Angelina’s public announcement of her choice will certainly help many women having to make their own decisions. This really is an individual issue.”

Raising awareness

Angelina’s story will change lives, believes Louise Bayne, chief executive of ovarian cancer charity Ovacome, which supports women worldwide. “We were saddened to hear that Angelina Jolie is a carrier of the BRCA1 gene and like many thousands of women has experienced the loss of a loved one from ovarian cancer,” she says, referring to the actress’s mother, Marcheline Bertrand, who died of ovarian cancer in 2007 at the age of 56. “However, her decision to make the knowledge of her surgery public has provided a welcome boost in awareness both about the BRCA mutations and the importance of knowing your family history in breast and ovarian cancer.” Women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer should talk to their family doctors, she says, and a health professional may consider a referral to a geneticist.

Families may also opt for testing, says Dr Ahmed. “If women carry a mutated gene it must have been inherited from one of her parents, so each of her brothers and sisters has a 50 per cent chance of inheriting the mutation,” she says. Men with harmful BRCA mutations also have an increased risk of male breast cancer and, possibly, of pancreatic cancer, testicular cancer, and early-onset prostate cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute.

So who should seriously consider testing? “Families with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer should take the test to know their inherited risk,” says Dr Ahmed. Marriage choices can also alter risk, she adds, since a faulty gene can be passed on from either side – whether or not it affects the first generation.

For Ann Wiltshire, though, the decision to get the test and act on the results was clear – she and Lyn are now supporting Ovacome because of their experiences. “The trouble with ovarian cancer is that it is often detected too late to be successfully treated because it is often confused with more common problems such as irritable bowel syndrome and the menopause,” says Ovacome’s Louise. “Only a fifth of cases are diagnosed early, but if it is caught early then the five-year survival rate is more than 70 per cent.”

While mastectomy and hysterectomy are both extreme operations, they are preferable to living with the high risk of cancer for many faulty BRCA-gene carriers. In the public announcement of her surgery, Angelina Jolie was clear that having the operation hasn’t changed the way she feels about herself and her femininity – “On a personal note, I do not feel any less of a woman,” she wrote in the New York Times article. “I feel empowered that I made a strong choice that in no way diminishes my femininity.” Following her mastectomy, Angelina Jolie is reportedly intending to undergo an oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) in order to minimise her risk of ovarian cancer.

Ann’s experience has been equally positive. “I feel really lucky to have learned about the risk in good time, while I’m well, and been able to do something about it,” Ann says. “Now I have the whole of the rest of my life to look forward to, without having to worry all the time.”

Are you at risk?

According to www.breastcancer.org, you’re substantially more likely to have an abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene if:

- l You have blood relatives (grandmothers, mother, sisters, aunts) on either your mother’s or father’s side of the family who had breast cancer diagnosed before age 50.

- l There is both breast and ovarian cancer in your family, particularly in a single individual.

- l There are other gland-related cancers in your family such as pancreatic, colon, and thyroid cancers.

- l Women in your family have had cancer in both breasts.

- l A man in your family has had breast cancer.

But remember, if one family member has an abnormal cancer gene, it does not mean that all family members will have it.

Look out for next week’s health article for more information on the risks and symptoms of ovarian cancer