As Laxmi Sargara pours the guests a cup of chai she can feel their eyes burning into the back of her head. She sits quietly in the corner of the room, trying not to listen to her parents talking to them but it’s impossible not to.

What she hears makes her want to scream. She looks at her parents for reassurance but she can see pain in their eyes.

The guests are Laxmi’s in-laws. She had been married to their son Rakesh as a one-year-old baby and had grown up never knowing.

Now her in-laws were here to collect her from her family’s home in the village of Luni to go and live with them in the neighbouring village of Satlana, Rajasthan, India.

Laxmi, who at 18 is the youngest of four brothers and a sister, says, “When I heard in April that I was married and my in-laws were telling my parents I should move in with them the following week I couldn’t digest any of it. It was simply shocking. I went numb.’’

Her marriage was part of a tradition called Mousar in Laxmi’s village community – when an elderly relative dies a younger relative gets married within 13 days. They say after a death, a marriage brings happiness and keeps away bad spirits. Usually, this tradition is followed when a close relative dies like a mother, father or grandparents. There is no grand function, and both the child bride and groom are just made to sit with each other followed by prayers. No money is involved.

When Laxmi was just 12 months old her grandmother died and her grandfather and uncle decided Laxmi should marry. They found three-year-old Rakesh from Satlana as the perfect match.

“There’s no mixing of girls and boys in my community,’’ she says. “They don’t talk to each other, particularly if they’re strangers. There are no love stories in our community. I’ve never spoken to a male stranger in my life and not a single boy has ever attempted to propose to me. Marriage in our community is about families, not individual needs. It’s our tradition.’’

The marriage took place in Khera village, five kilometres from Laxmi’s home, and her parents were not aware of the ceremony. As in many communities in India, the uncle and grandfather are as much involved in the lives of the children as the parents are, so when they took her away for the marriage ceremony, her parents didn’t suspect anything.

Her father, Teja Ram Sargara, 50, and mother Sukdi, 45, found out a few weeks later but could not object, as it was tradition and culturally respectful to adhere to the wishes of the rest of the family. Nothing was said of the marriage again… until Laxmi turned 18 in April this year.

A happy and secure childhood

“I had a lovely childhood,’’ Laxmi recalls. “I enjoyed playing with my friends; I helped my mother in the house and loved my father dearly. I went to school for a while but I didn’t like it, and education isn’t needed in our community, so I just left.’’ Laxmi doesn’t remember hearing about child marriages while she was growing up and can’t recall seeing any of her friends fall victim to one.

“I don’t remember my friends getting married at a young age. Actually most of them are getting married now at 18. But I’m not sure whether these are child marriages and they’re only now going to live with their husbands or if they’re simply getting married now. It’s crazy that I never picked up on anything but I was in the complete security and happiness of my own home and family – well, so I thought.’’

She knew one day she would get married and was happy about that but thought she had a while until her big day. Laxmi, like many girls in her community, relies on her parents to find her a husband. She thought once she was old enough they would find her a good partner. “Our social system doesn’t give us the freedom to choose our own partners,’’ she adds. “I was always ready to marry someone when my parents thought I was ready.’’

However, Laxmi never thought her parents would allow something as deceitful as marrying her off as an innocent one-year-old child. As soon as her in-laws left that day Laxmi cried and begged her parents not to send her to live with them.

She was terrified of living a life she wanted no part of, even though she understood it wasn’t her parents’ fault.

“My parents have always loved me; I have no doubt about that. Social expectations are hard, especially in our world.

“I know they wouldn’t have had much choice in the situation. As a female, my mother wouldn’t have any authority in any decision making, even about me and my life. It’s only the men who decide for the entire family.’’

She gathered her courage and fled

When Laxmi’s in-laws visited that day, her parents initially tried to persuade her to follow through with what was expected of her. But when they saw how distressed Laxmi became they changed their minds.

Eventually, so scared was she of what her in-laws might do for not adhering to her society’s norms, and not trusting her family to support her fully, Laxmi decided to run away from home.

She had never left the safety of her village before, but her courage found her catching a bus to the nearest city, Jodhpur, 40 kilometres away from Luni, in the state of Rajasthan.

There she found her older brother, Hanuman, 32, where he was working as a labourer and living with his wife and two children.

“As the Akshaya Tritiya festival was approaching in April this year I became more worried,” Laxmi recalls. “It’s the time when many marriages take place, it’s tradition, so I knew if no one defended me I’d have to move to my in-laws then. I was scared.

“Even though I’m happy that my parents would always find me a good match I knew I would have the last say. But this was out of my control, I had no say. And my in-laws scared me.

“In the end I just left home. I knew my brother would help me.” Hanuman had found out about his little sister’s child marriage about six years ago. “I learnt about her marriage when she was around 11 years old. It’s very normal in our community so I didn’t worry about it. But when I found out she was so upset and was so sure she didn’t want to go to him I had to help her. I just want my sister to be happy.’’

When Laxmi arrived at Hanuman’s doorstep at first he had no idea how to help her. Eventually he turned to a charity that supports local men and women in need, Sarathi Trust. Laxmi sought advice and guidance from the charity as her next course of action.

Thanks to the person running the charity, Kriti Bharti, and the government’s Women and Child Development Department, Laxmi was finally in safe hands.

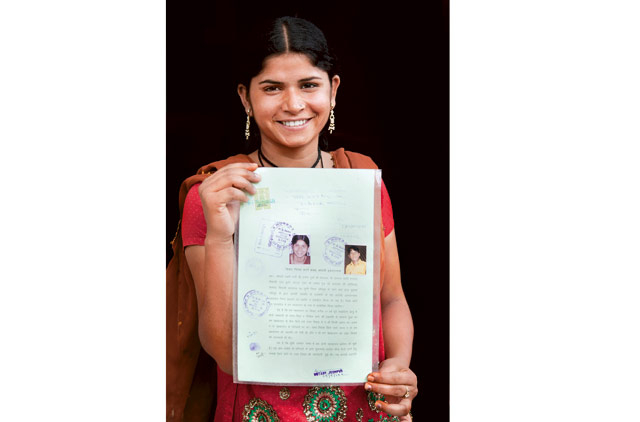

Official confirmation that it’s over

Although child marriages are now illegal in India, Laxmi was desperate for something official – such as a divorce – to end the saga.

Eventually, under The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 (PCMA) she was able to void the marriage.

“Laxmi had no proof of age, no birth certificate or identity card so we had to seek medical assistance such as a report from a doctor to prove her age,” says Kriti. “But once her age was confirmed we were able to annul her marriage on the eve of Akshaya Tritiya.

“It was a good date to honour such a victory as the festival influences a lot of child marriages. We wanted to send a strong message out against child marriages and this date was perfect timing.’’ Although the law doesn’t recognise these marriages at all, in this case, Laxmi wanted a legal document, which could be used to counter the tradition of child marriage, so asked the court agreed to annul the marriage.

Both Laxmi and Rakesh signed the annulment document, which cost Rs1,000

(Dh67). Indu Chopra, Programme Director of the government’s Women and Child Development Department, says, “Laxmi’s case is a milestone in the fight against child marriages. It will inspire many to break this barbaric tradition.

“This is the first case in India where a girl has annulled her child marriage and we’ve since received requests from many girls to annul theirs too.’’

Plans for an independent life

Laxmi is still too scared to return to her village as she fears she will be beaten by neighbours for going against the society mores. She is also worried that she will not get the respect and dignity from the villagers so highly valued in Indian communities. Meanwhile, she remains with her brother and is working with Kriti and the charity to build her confidence and learn a craft so she can look after herself.

“I feel light and free since the annulment. It feels good and I’m happy,’’ she says. “I’ll stay with my brother for at least a year until all of this mess has settled down. Some villagers and certain members of my family are still angry with me.

“I would like to learn tailoring and start my own boutique and then I’ll think about marrying. It won’t be until next year though. And I’ll still let my parents and brothers choose a husband for me.

“Being married off as a baby is horrendous. I just felt like a slave. Eventually I will trust my parents to find me a good match, then I’d meet him, and if I didn’t like him I’m quite entitled to refuse and they will look again. But it would be my choice. And as a human being I absolutely have that right.

“I still respect my parents’ decisions and wishes after all. But I will most definitely have the last word this time.”