Children of the Jacaranda Tree,

By Sahar Delijani,

W&N, 288 pages, £12.99

A first reading of the “Children of the Jacaranda Tree” evoked a great, gentle wash of sadness. But the beauty of the prose lies in the catharsis Sahar Delijani weaves in gradually — delicately done, as if measured in perfect amounts and diffused like a fragrant scent — within the story as it spins an intricate web enveloping the protagonists and other characters in post-revolution Iran.

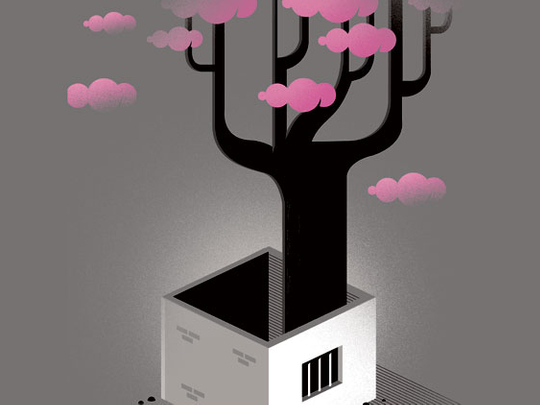

The novel is an evocative reminder of the eternal spirit of resistance, sacrifice, love and hope. This first published work by the enigmatic Iranian author Delijani impresses with its powerful symbolism of resistance, courage, defiance, hope and love. Who are these children whose parentage has been allotted to the jacaranda tree by the author? The tree itself, with its spreading branches laden with purple flowers, is the source of comfort and love, offering a glimmer of hope to all those whose footsteps have led to rest or play in its shade.

Opposed to the jacaranda tree, the wellspring of life and the human spirit, is the Evin prison, whose high grey walls stand for the ugliness and repression. It represents the oppressive system that has broken innumerable spirits and taken many human lives, robbing even those related to its inmates of happiness and hope. But, strangely, the same Evin, while crushing the voices of dissent, has perpetuated a cycle of resistance. Its tale is unfinished, for the system at present may be much stronger in controlling the voices seeking freedom and change, but there is no rest, neither for the “system” itself nor for those who continue resisting — these are the children of the jacaranda tree. In Evin, one side represents systematic repression, the other resistance. Browbeaten, crushed and broken, those who are let go from its dark bowels continue to keep a small flame burning inside, whose legacy they pass on to their children.

The author’s struggle for healing of old wounds, afflicted on her family and their friends, is interwoven throughout the narrative. Yet it never collapses under the terrible weight it represents. It stands feebly at first and then gains sustenance from the experiences of others who all stand linked in a constantly meandering stream of consciousness. The narrative maintains a fine balance, juxtaposing the beauty of a people and a rich culture with the darkness of an oppressive system and the betrayal of ideals.

The opening scene itself carries the reader forward on a tumultuous ride riddled with pain. The ordeal of Azar, as she grits her teeth and braces against all odds to save herself the humiliation of giving birth in the prison van, provides the dramatic framework and prepares the reader for what is to come. It is gory, tragic, but liberating at the same time. As Azar swallows her grief at being forcibly parted from her newborn baby girl, she overcomes one more hurdle of fear the authorities erected. There are many partings, and as often is the case, most of them are tragic. Whether it is Leila’s parting from Ahmad for the sake of her parents and her sisters’ children or little Omid’s parting from his mother when she is arrested while he is sitting at the dining table having his yogurt — its cold delicious memories laced with roses and a vision of his mother’s beautiful presence remain potent in the reader’s mind long after they have finished reading the book. One of the most touching parts of the novel is of Maryam’s husband making a bracelet from date stones for his daughter who is born while he is in prison and then managing to send it with the baby, undetected, when she is allowed a visit.

Equally disturbing is the discovery of their parents’ past by the children when they have grown up and are forced to come to terms with it. The discovery serves a dual purpose. The ingenuity of the prose is to convey it as a means of healing for the sufferers and a source of understanding and reconciliation between the children and the parents, whose relations have been scarred inadvertently by the lacerations of the unknown and the unspoken. Within the suffering lies the healing and the salvation.

Spanning the decades from 1983 to 2011, the novel measures the struggle of the generations in a transcendental manner, leaving in its wake a poignant question hovering near the surface: Would the pain and suffering of these children’ parents and previous generations go to waste or will they pick up the courage to cup the flame and allow it to burn brighter?

An outstanding feature of the novel is how political dissent and desire to bring about change is interspersed with the heartache and love, the struggle of daily lives and ordinary aspirations, in perfect harmony. While “Children of the Jacaranda Tree” is not the first novel depicting the struggle of closed, oppressed societies it is powerful enough to set a precedent, emblematic of the challenges facing the younger generations today. No doubt they want to help achieve the goals their parents and older generations sacrificed so much for. For some it would be speaking about the atrocities committed on their loved ones’ and raising awareness, whether living inside or outside the country.