It is easy to imagine that “Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes”, a vast, dense and beautifully installed new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, began as a kind of parlour game. You can almost picture the curators, Jean-Louis Cohen and Barry Bergdoll, brainstorming to come up with the most unlikely, counter-intuitive thesis about Le Corbusier they could — and then setting out to defend it with straight faces, deep scholarship and a good deal of museological firepower.

The thesis is that Le Corbusier was an architect who put concern for the natural world at the centre of his work. The show argues that his vision, as the opening wall text puts it, “was profoundly rooted in nature and landscape”.

The conventional wisdom, of course, has long been essentially the opposite: that Le Corbusier, who was born Charles-edouard Jeanneret in a small French-speaking Swiss town in 1887 and adopted his pseudonym in his 20s, designed his white, streamlined modern buildings in strict separation from the natural world. He famously called his flat-roofed houses “machines for living in”; he was obsessed not with the organic forms that inspired Frank Lloyd Wright but with planes, sports cars, freeways and the efficient shapes of factories and warehouses.

Summing up the typical view, architect and critic Peter Blake wrote in 1960 that Le Corbusier believed a building “should stand in contrast to nature, rather than appear as an outgrowth of some natural formation”.

In general, I admire and even find myself rooting for museum shows that advance surprising arguments about well-known architects. But this effort to go against the grain of architectural history is a contradictory one, in certain ways divided against itself — in part thanks to how much material it puts on view.

For nearly every model or photograph in the show that supports the idea that Le Corbusier’s work was defined by a profound and overlooked genius loci, there is another that casts him in a more familiar role: as a radical remaker of cities happy to raze forests and pave over fields to make way for a bold new architecture.

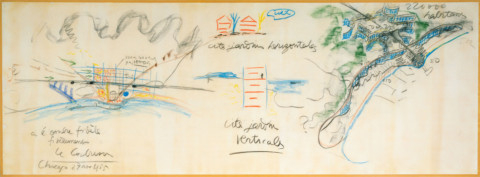

Bolstering the curators’ case are sketches, watercolours and paintings by Le Corbusier, many of them borrowed from the Corbusier Foundation in Paris, as well as sections on his 1955 Notre-Dame du Haut chapel in Ronchamp in eastern France, and a full-scale reproduction of the interior of the tiny wooden vacation cabin he designed for himself on the French Riviera.

The museum has commissioned new photographs by Richard Pare of the architect’s best-known projects, including the 1929 Villa Savoye near Paris; not surprisingly most of these pictures show the buildings framed by or emerging from thickets of greenery.

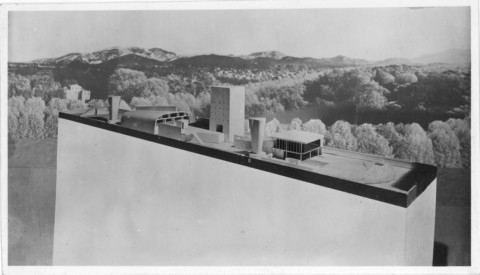

But Le Corbusier’s tendency to produce buildings estranged from nature is also very much in evidence. The show includes several models of towers and other buildings that seem to swim in empty space, looming over denuded landscapes that contain either no trees or a token, scraggly few. Or take a 1934 urban plan for the city of Nemours, in Algeria. A large model of that proposal in the exhibition shows 19 modernist boxes marching across a waterfront landscape.

Maybe the apartments inside those wide slabs have terrific views, and maybe the creation of those views counts distantly as a kind of sympathy to place. But on the whole the project is sensitive to its site the way a tank is sensitive to the territory it rumbles over.

There is no doubt that our understanding of Le Corbusier’s approach to nature could use an update. The Ronchamp chapel, which I visited in May, is among the most sublime readings of site and topography produced by a modernist.

The building, finished when the architect was 67, trades the flat roofs and taut planes of his youthful work for more flexible forms and a deeply affecting, brilliantly executed primitivism. (Imagine an early Corbusian building redrawn by Philip Guston.) The chapel crowns and yields to the hill at the same time.

But was the sensitivity reflected in that design a constant in Le Corbusier’s work? Or was it a kind of architectural wisdom or perspective earned over time?

The exhibition, for all its sprawl and size, also pays little attention to Le Corbusier’s writing, which helped propel him to fame in the 1920s and 1930s. The reason isn’t hard to divine: It was in his books that the architect set himself up most clearly against nature.

A determined group of curators and architectural historians has spent much of the past two decades arguing that modernist architecture was more layered and complex than the movement’s early manifestos and most strident champions (read: Philip Johnson in his MOMA days) let on. This effort has produced a good deal of significant scholarship, rescuing architects as different as Hawaii’s Vladimir Ossipoff and the Southern Californian Gordon Drake from near-total obscurity and making clear that significant modern buildings often drew from local, regional and even vernacular sources.

But in bringing that campaign to the very centre of purist abstract architecture, right to Le Corbusier’s door, Cohen (a guest curator who has organised a number of important shows on modern architecture) and Bergdoll (head of MOMA’s department of architecture and design) inadvertently suggest that this remapping of modernism may have overextended itself. In trying to make one of the most aggressive defenders of a universal style look actively accommodating to nature, they threaten to defang an architect whose books and buildings had terrifically satisfying bite.

“If there is a blind spot in the astonishingly vast literature dedicated to Le Corbusier,” Cohen writes in the show’s catalogue, “it is certainly his relationship to landscape.”

The logic inherent in that sentence strikes me as nearly backward. Like the organisers of a show celebrating Picasso’s underwater scenes or the tall buildings of Craig Ellwood, the curators have mistaken the underappreciated for the largely nonexistent. They have been so eager to find an available category in Corbusier studies to fill with a big new show that they glide right over the idea that there may be a good reason it has stayed empty all these decades.

It is certainly overstating the case to claim, as Bergdoll does in his own catalogue entry, that “the experience and cultural meaning of landscape was in many ways as central to Le Corbusier’s vision of design and his conception of architecture and cities as it was to architects more commonly associated with the organic, such as Alvar Aalto or Frank Lloyd Wright”.

Sure, many architectural historians have been too harsh in calling Le Corbusier’s buildings universally hostile to the natural world. And there is absolutely a sense that his midcareer houses, especially, gained power by setting themselves up in stark, angular contrast to nature.

But the curators make much bolder claims than that. And even many full-on admirers of Le Corbusier’s work — and I am one — would acknowledge that the blind spot Cohen refers to is less in the scholarship than in the architecture itself and even more in the polemical theory that Le Corbusier produced to promote his buildings.

Just because the conventional wisdom about Le Corbusier isn’t entirely right, in other words, doesn’t make it entirely wrong.

–Los Angeles Times