A memorial to the stories of India’s partition

Through survivors’ tales of sorrow and courage, a museum aims to commemorate the violent event that shaped the subcontinent

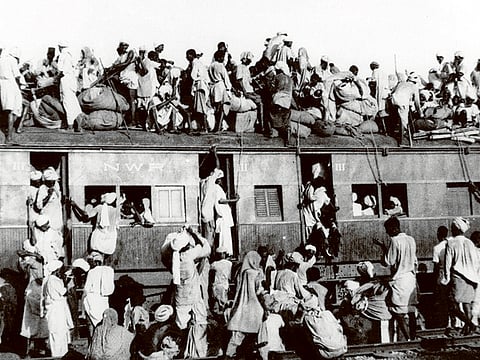

History is arguably cyclical, often destined to repeat itself in myriad ways. In 1947, the largest mass migration of recent history occurred as a result of the partition of the Indian subcontinent into the Dominion States of India and West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

According to the UNHCR estimates, 14 million people were displaced during the partition and compelled to rebuild their lives in new homelands; it was accompanied by a tremendous outbreak of violence and bloodshed with about 2 million people estimated to have been killed. Hundreds of thousands did not even make it to their destinations.

Given the contemporary global scenario, with vast numbers of people migrating from their homelands to foreign countries, the partition of the Indian subcontinent assumes a great topical and historical resonance today.

Today’s refugees can perhaps understand the 70-year-old pathos of those who left a place they had called home all their lives without knowing that return would be impossible. Today’s refugees will be able to strongly relate to the pain experienced by partition survivors who were separated from their families and friends forever.

The common bond that unites all refugees is ultimately that of exile, the yearning for and inability to return home, and the challenges of rebuilding their lives after all has been lost.

The politics that led to the partition were complex but essentially a result of the divergence of the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, the latter spearheading the creation of a Muslim state — Pakistan — as India sought independence from centuries of British colonial rule.

The British invited a judge, Cyril Radcliffe, a person who had never previously visited India and knew little of it, to draw the borders of India and Pakistan in seven weeks; the borders were eventually declared two days following independence.

With a single stroke of Radcliffe’s pen, villages, families and communities were torn asunder, the partition dramatically impacting the two nations that sprang forth from the former one nation, leading Mahatma Gandhi to powerfully describe it as a vivisection.

It was both an enduring personal connection as well as feeling impelled to memorialise it at the national level that led Lady Kishwar Desai to conceptualise the idea of the Partition Museum.

A phrase often used to describe the Partition is “the wound that never healed”. Desai would constantly listen to and absorb her parents and their friends’ reminiscences about the event. She also encountered partition in literature. An author and a playwright, Desai’s first play was about the acclaimed Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto, whose performances ran for 20 years.

Many of Manto’s visceral short stories dealt with the partition, including, arguably his most famous story, “Toba Tek Singh”. “People were palpably reacting to it as they watched the play — and yet, I also felt that partition was the place you didn’t want to go back to: it was a dark room of sorts, embodying a reluctance to confront and examine the issues,” she says.

Desai’s desire to memorialise the partition in a physical space became much more focused a decade ago. “I observed that people were collecting and documenting memories and stories online — and it struck me that enough time had passed, we must do something about it,” she says.

After all, partition did not just exclusively represent recollections of grief, sorrow and separation; it also contained with it a valuable hope for the future. “It is only when you know these stories that you can talk about them. This became my motivation. We have to deal with the question: why did people do this to each other? By not talking about it we are ignoring the pain and trauma of those who experienced the partition. We have to acknowledge this happened, confront, accept and deal with it,” she says.

Why did it take so long for such a museum to come into existence? “Actually, one of our board members, Kuldip Nayar, had broached the idea of creating a memorial or a museum dedicated to the partition in the 1950s. However, the 1950-60s were a period of idealism, meditating upon that all that had been sacrificed towards building a new country,” says Desai, suggesting an inclination of the people towards possible social amnesia. “The partition had been very disturbing, the focus was now towards building a new country.”

Desai says her generation consequently did not entirely grasp the enormity or significance of the partition — it was as if the older generation was insulating them from the heartbreaking memories; the focus entirely shifted towards looking to and constructing the future.

“However, more than 70 years have passed and we can now examine the event through the prism of history. We also have many people in their 80s or 90s who experienced the partition and who constitute our heritage. How can we let their sacrifice go unrecorded? I feel very sad about it as fewer and fewer people who hold these memories remain,” she says, adding that those who had witnessed the partition find it very cathartic to speak about it. They express the desire for their children and grandchildren to know about the event, too, she says.

The decision to open the museum in Amritsar was taken because of its bloody links with the partition. It was the first railway station for trains coming from Lahore, and witnessed much of the bloodshed that occurred. “There is a strong historical motive behind our decision to have the museum in Amritsar as opposed to, say, Delhi,” Desai says. “Amritsar seemed to be apt as it was vastly and intensely affected.”

Besides, Amritsar is also adjacent to the Wagah border, where the Border Ceremony occurs every day. It is a military practice that the armies of India and Pakistan have followed since 1959. People come to witness the ceremony every day and engage with the idea of a border, perceiving it as tangible entity rather than an abstract one.

Given that it is a crowdfunded museum, it was financially more viable to have it in Amritsar. “We’ll start with Amritsar, but exhibitions will be held in Delhi and Kolkata later,” Desai says. “We are grateful to the Punjab government for allocating the west wing of the Town Hall for the museum. It speaks of the high stature of people and the quality of their stories; it commemorates them in the way that it should.”

Being crowdfunded also makes the museum speak the language of the 21st century. In traditional museums, one admires old antiquities for what they are; there is notably an absence of a personal connection and intimate knowledge with those objects, rendering them as firmly entrenched in the annals of the distant past. The Partition Museum will admit people who lived through it — they can look at photographs of the partition or refugee camps and recognise themselves or their parents in them.

Describing it as a living museum, a people’s museum, Desai says it will essentially be a museum of memories, wrought from personal connections and stories, oral histories and objects that crossed the newly demarcated border. “My mother brought a book of art that her mother had in turn carried over, thus creating a dialogue about the kind of things people chose to carry when leaving home and crossing the border.”

A constantly evolving museum, it will be largely based on people’s accounts, making the people both participants and the audience. “It’s distant and yet not so much,” Desai says.

“The younger generation is very keen to connect with the idea of partition. What was disturbing for me was that other countries have confronted their historical demons, be it Germany with the Holocaust or South Africa through the apartheid. They must have gone through their own painful and challenging journey while confronting these inescapable historical truths,” she says.

Why was there a lacuna when it came to the partition of India, she wondered. “You can’t walk away and shut the door behind you, and it was singularly important that children and young adults know about what had happened.”

Desai also emphasises the significance of sharing stories of grit and courage relating to the partition. “We would like to show how many rebuilt their lives in new places. They left huge business establishments back home to start from scratch,” she says, noting that the museum recognises the stories of those people who did not have the luxury of mourning: they simply got on with the business of rebuilding. “It is important to delineate that had they not peacefully moved on with their lives, today would have been very different and India wouldn’t have been what it is today; the tremendous role they played in building a new nation must be documented as well.” Considering many leading business families of India today were once post-partition refugees, the contemporary and future generations will become aware of the that generation’s resilience and the sacrifices it made.

The Partition Museum seeks to pay a heartfelt and powerful homage to an event that literally and definitively shaped modern India.

Priyanka Sacheti is a writer based in New Delhi, India.

For more information on the Partition Museum or to make a donation, visit www.partitionmuseum.org

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox