San Francisco: Technology stocks are gyrating. Valuations for once-vaunted private companies have been slashed and some start-ups have shut down. Even Apple’s chief executive, Tim Cook, recently said he was “seeing extreme conditions unlike anything we have ever experienced.”

But in Silicon Valley, ask any start-up entrepreneur about the shifting economic environment and the answer often goes like this.

“I haven’t changed anything since this all started,” said Manav Mital, chief executive of Instart Logic, which speeds the delivery of computing services to customers.

“The pullback hasn’t affected our hiring plans at all,” said David Vivero, chief executive of Amino, a free service that matches patients with doctors for appointments. He added that he was looking to increase his workforce by about a third.

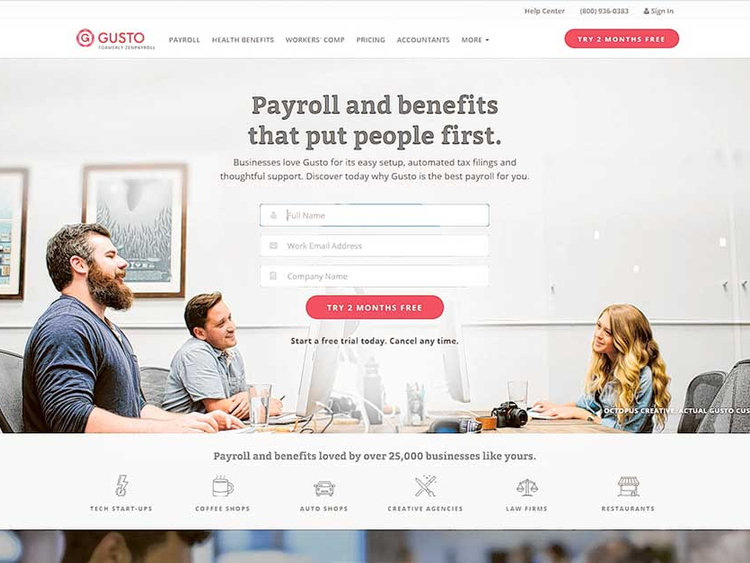

Nor has the downturn changed life at Gusto, a payroll management start-up. “I’m excited about the shift,” said Joshua Reeves, a founder of the company. “Even in downturns, some businesses succeed.”

In technology, there is reality, and then there is start-up reality. Even as the tech industry is undergoing a reset in expectations driven by global economic concerns, many start-up executives say their companies are doing just fine. Those layoffs that are starting at small private tech companies? That decline in start-up funding? Maybe some start-ups are feeling it, but not their own.

“It’s always the other guy who will suffer,” said Venky Ganesan, a managing director at the venture capital firm Menlo Ventures, which has invested in the ride-hailing company Uber and the food-delivery start-up Munchery. “I’m no psychologist, but all the people we’ve backed have never been average. They never think the things that happen to average people will happen to them.”

Entrepreneurs’ confidence levels remain buoyant even though investors are telling them that the change from go-go-go times to merely go-go will have consequences.

The message from Rory O’Driscoll, a partner at Scale Venture Partners, that entrepreneurs should be more careful is often ignored. “There hasn’t been a company where the pullback in funding hasn’t been discussed,” he said. “But if a person has had a conversation about this 10 times and it hasn’t sunk in yet ...”

O’Driscoll’s voice trailed off. “I’m tired and grumpy because I’ve had three of these conversations today and in every one you have the same discussion,” he said.

At start-ups small and large, “there’s still not enough caution,” said Jim Breyer, a venture capitalist at Breyer Capital, who was one of the earliest investors in Facebook. Breyer predicts that over the next two years, 90 per cent of the privately held companies valued at more than $1 billion (Dh3.6 billion) will see their valuations fall.

For now, start-up entrepreneurs are operating much as they did during the recent boom times. Data from Jobvite, a recruiting service used by start-ups, show no drop in hiring activity or salaries in the San Francisco Bay Area. Well-appointed offices that look like photo shoots for Design Within Reach and perks like free Uber rides and in-house meals remain common at the companies.

“The narrative of start-up comeuppance is in the air, but we haven’t seen a statistically significant change in food budgets,” said Arram Sabeti, chief executive of ZeroCater, which serves meals to tech companies.

In fact, the food from tech companies that goes uneaten is piling up. “Two years ago, we picked up 15 tonnes of food a week and now we’re picking up 17 tonnes a week,” said Mary Risley, whose group Food Runners in San Francisco distributes leftover office food to the city’s homeless residents. She attributes the increase largely to start-ups.

At Instart Logic in Palo Alto, California, the company recently hired a sales executive to help drive an expansion, using money from a $45 million funding round last month.

“I’ve been reading a lot about a slowdown and asking myself about what it means, but we just closed a substantial round of funding,” said Mital, characterising his recent financing as “one of the easiest fund-railings we’ve had.”

Many entrepreneurs seem to maintain a blithe disregard even though the deflating private market is a constant topic of conversation at tech conferences, private dinners and fetes thrown at the Battery, a San Francisco private club known for its tech-heavy membership.

The air of detachment pervades the talk. Shan Sinha, chief executive of the video conferencing start-up Highfive, said his customers were discussing ways to save money over the coming months. But he said he and his founder friends wonder “whether what’s happening in the world will have an effect on us.”

Other entrepreneurs emphasise that any downturn will be good for them. Less venture capital money should lead to fewer competitors; a less crowded market may also make it easier to recruit talented people. Gusto’s Reeves said that if his customers found themselves in financial straits, that would create another great selling point for his company, which can help businesses save money.

“It’s awesome to see this conversation come up,” Reeves said. “Most have only known the froth of the cycle. Now it’s time to create companies to solve real problems.”

Start-up employees, on the other hand, seem more circumspect than their bosses. Last year, many saw the value of employee-issued shares at formerly highflying businesses drop, creating more interest in the nuances of their compensation packages.

“When I bring up issues that could impact the value of their stock, employees want to talk about them,” said Mary Russell, a lawyer based in Palo Alto, who counsels individuals about their equity compensation. “Last year there was less concern.”

The message of more caution is not lost on all start-ups. Some are cutting back on expenses, albeit just a little. Jeff Selzer, manager of Palo Alto Bicycles, a speciality bike store, said he was seeing fewer start-ups build custom, $10,000 bicycles as signing bonuses for new managers.

Others are going further. Origami Logic, a marketing analytics start-up, held its annual off-site meeting for salespeople last month at a rustic coastal lodge near Santa Cruz, California. The company said that other start-ups typically hold such events at luxury hotels in San Francisco or Las Vegas, which can cost twice as much.

And Ben Katz, founder of the mobile banking app card.com, said he had found ways to save more than 30 per cent a month on his company’s computing services bills by using less server space. He is looking to sublet a 100-square-foot space in his office to save $12,000 a year.

“In the past, we wouldn’t have justified taking the time to do little things like that, but now we take time to find ways to grow sustainably,” he said.

Still, confidence reigns.

“We can make a compelling case that our software will help save money during a downturn,” said Greg Waldorf, chief executive of Invoice2go, a start-up based in Silicon Valley and Australia that makes an invoicing app. Another plus, he said, was that his own company did not burn through cash at a fast rate. “For us, it’s business as usual thanks to how I’ve been leading the company.”