New York: The Olympics are full of stories of underdogs triumphing against the odds for athletic glory. But in the case of Olympic marketing, smaller brands are finding it tough to prevail amid strict rules.

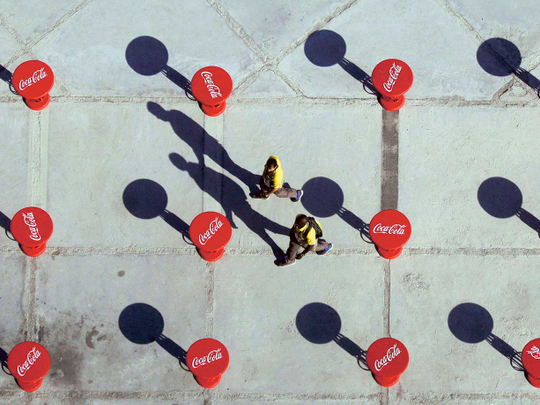

Sponsors such as Visa, Samsung and Coca-Cola pay hundreds of millions of dollars to be associated with the Olympics. So the International Olympic Committee cracks down on non-sponsoring brands that reference the Olympics by name or use Olympic logos in tweets or advertisement.

This extends to athletes who tweet about “non-Olympic commercial partners” — brands that sponsor the individuals but don’t pay the IOC or a national Olympic committee itself to be an official Olympic sponsor. The IOC can punish athletes for rule violations by disqualifying them from events and even stripping them of medals.

But in the age of Twitter and Facebook, it’s difficult to clamp down entirely on messaging. The IOC tried to relax the rules this year to make it easier for non-Olympic brands to advertise. Some brands took advantage of that, but others were left frustrated by the hoops they had to jump through to qualify.

Long in place, the Olympic Charter’s Rule 40 limits athletes, coaches and other participants from appearing in advertising and other marketing, including social media posts, without the IOC’s permission. Participants are also forbidden from wearing clothing with logos of non-Olympic brands.

Although the blackout period covers just one month — from July 27 to August 24 for the Rio Olympics — it’s a crucial window for many brands because for many athletes, this is the only time they have the world’s attention.

There’s a long list of words that advertisers can’t use, ranging from obvious ones like “Olympics” to seemingly benign ones like “effort” or “performance,” depending on context. The IOC says the rules are in place to protect its sponsors’ investment and prevent “over commercialisation.”

Frustrated by their inability to mention their sponsors, dozens of athletes launched a Twitter campaign during the 2012 London Olympics to urge an end to the rule. In an attempt to address the problem, the IOC modified the rules to let brands apply for an exception.

This year, brands could feature Olympic athletes in ads as long as they applied for a waiver, avoided certain words or logos and started their campaigns by March. IOC spokesman Benjamin Seeley said in an emailed statement that about 1,000 brands applied and were approved.

Under Armour and Gatorade, for instance, came out with ads featuring swimmer Michael Phelps and tennis champ Serena Williams, among others, even though neither is an official Olympic sponsor.

But many smaller brands found the changes unfeasible. Unless an athlete is a superstar like runner Usain Bolt, it’s hard to know in January whether an athlete will become an Olympian. And because the ad campaigns have to run continuously beginning in March, many smaller companies couldn’t participate with their limited ad budgets.

“At first the waiver process did seem like a viable option, but when we started going down that path, we realised... it’s hard to do that in a generic, approvable way,” said Jesse Williams, senior global sports marketing manager at Brooks Running, which sponsors eight Olympic athletes around the world, including US runner Desiree Linden and decathlete Jeremy Taiwo.

The relaxed Rule 40 rules “only benefit brand name athletes,” said Christopher Chase, a partner in the law firm Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz. “If you’re a [lesser known] Olympic rower or shot putter, it’s a great time to thank sponsors, and they can’t do it.”

To protest the rule, Brooks created a guerrilla marketing campaign — anonymously at first, until The Wall Street Journal identified the company by tracing internet-registration records. The protest site offers downloadable bright yellow signs that carry such messages as “good luck, you know who you are, on making it you know where.”

Williams said that even though the campaign isn’t anonymous anymore, the media attention it has gotten has been good.

“It’s cool to see a movement or conversation starting,” he said. “We really hope to continue to help fuel that. “

Another athletic apparel brand, Oiselle, got in trouble after it congratulated a runner it sponsors, Kate Grace, on becoming an Olympian and going to Rio on an Instagram post after a qualifying event. The US Olympic Committee demanded that Oiselle remove the social media and blog content because it violates Olympic trademarks.

The Seattle company complied, but CEO Sally Bergesen complained on the company’s blog that for smaller brands, “it reduces the benefits of participation in the programme to a practically non-existent level.”